Remembering the Romans in the Middle East and North Africa: memories and reflections from a museum-based public engagement project

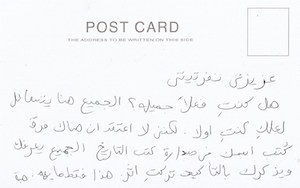

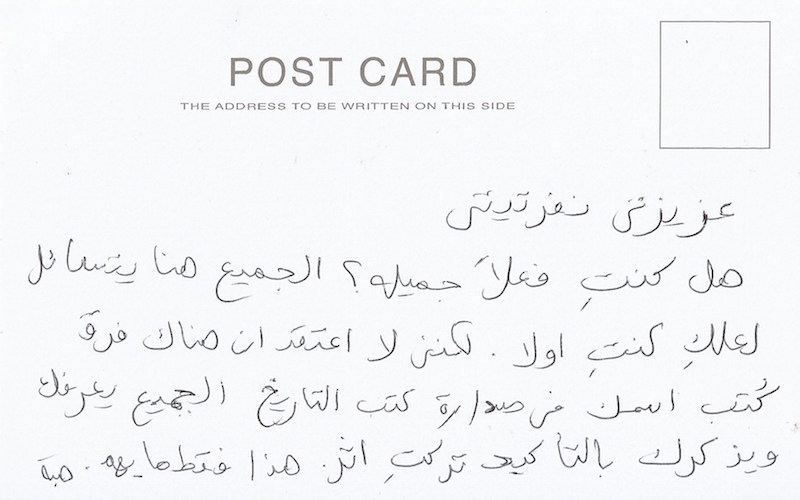

Dear Nefertiti,

Were you really beautiful? Everybody here asks, maybe you were the first (to ask). But I do not think it makes a difference. Your name has been written at the forefront of history books. Everybody knows you and remembers you. Certainly, you left a trace. This is what matters.

Heba

Introduction

Zena Kamash

‘Remembering the Romans in the Middle East and North Africa’ (‘RetRo’) was a public engagement project, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) Cultural Engagement Fund, that took place in spring 2016 and comprised four day-long workshops at the Petrie Museum, London and the Great North Museum, Newcastle. In addition, three days were spent gathering memories and responses to the recreated Triumphal Arch of Palmyra that was set up in Trafalgar Square, London. The focus of this article is on the workshops strand; information about both elements, including a gallery of everything created in the workshops, can be found here.

The workshops were a collaboration between Dr Zena Kamash (Principal Investigator), Dr Stephen Smith (AHRC Cultural Engagement Fellow), Dr Sarah Ekdawi (creative writing expert), Miranda Creswell (artist) and Rory Carnegie (photographer), ably supported by three MA students from the University of London: Felix Charteris, Zoe Glen and Amy Wood. For each set of workshops, specific Roman-period objects were chosen in advance that could be handled by the participants; participants were also free to make use of the wider collections on display and so were not restricted to our pre-selected objects, nor necessarily to objects from the Roman period. On each day participants were provided with an introduction to the collections from a curator and then were invited to choose one or more objects, which they felt ‘spoke’ to them in some way and to respond via creative writing, drawing and photography. These media were chosen as they reflect the three parts of the archaeological record: written, drawn and photographed.

The creative mentors – Sarah, Miranda and Rory – were on hand to guide participants in their specialist field. In this, we built on a technique of ‘gentle engagement’ – not imposing our views or approaches, but instead chatting to people involved and providing soft nudges when requested to promote an informal and relaxed environment – that Miranda and I had developed in a former collaboration; nibbling on baklawa helped here too. In addition, everyone – curators, MA students, me – was free to engage in the creative writing, drawing and photography, and in so doing was also pushed beyond our usual practice. As part of this ‘gentle engagement’, we felt that a formal and intimidating feedback form to fill in at the end of each workshop would be a mistake and instead invited people to contribute to a guestbook. As well as writing thanks and thoughts about the day, some people chose to put their creations into the guestbook too.

The inspiration for the project came from a wish to promote a more positive narrative around archaeology and heritage in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, in the face of conflict and destruction. As someone of Middle Eastern origin, whose heart has been broken many times over by various news reports, this was keenly felt. In particular, I wanted to encourage the creation of new memories of the past in order to help people reclaim a part of their heritage and identity that was, and still is, being stripped away. Furthermore, I felt that this represented an alternative, more creative approach to the numerous projects that focus on reconstructions of sites in the MENA region, including, but not limited to the Institute of Digital Archaeology’s Arch of Palmyra, Iconem and Factum Arte. Instead, it was hoped that a more creative approach would help to bring people, as well as sites and objects, back into the picture.

Following on from the collaborative nature of the workshops, this article comprises the reflections and memories, one year on, of people who participated in the workshops, in whatever capacity. Everyone was invited to contribute, if they wished and to discuss one, or more, of their creations in any media from the workshops; the images are of those creations, accompanied by brief descriptions of the museum objects. My approach to the editing has been deliberately ‘light-touch’ as a key wish for this project was for people to find their own voices in a museum setting. Several themes emerge from these varied voices, reflecting engagements with the objects at a variety of levels: from the individual object, to the nature of the museum collection, to the role of people and communities. This multivocality, however, also brings out numerous subtle differences in experience, even in responses to the same object, for example the African red-slip ware flagon from the Great North Museum collections, reminding us that no two encounters with an object or a museum are ever the same.

Reflections

Heba Abd el Gawad

participant; creative writing

Ink drawing of Nefertiti on a limestone block, Petrie Museum, UC011

Within the walls of the Petrie museum the multiple, difficult and contested stories of the emergence and the development of the field of Egyptian archaeology and its collections are entangled. As an Egyptian archaeologist, I wandered around its galleries guided by my professional knowledge of the objects and absorbed by my “native memories” of the sites, I could not help but question to what extent are we – the local communities – involved in the recollection and modern shaping of the memories of our ancient past?

In a limestone depiction of the head of Queen Nefertiti I found my answer. The Amarna period provided a distinctive analogy of the complicated relationship between the “community of place” and the “community of experts” within the field of Egyptian archaeology. In establishing his regime Akhenaton adopted an inward-looking exclusive strategy. He isolated himself geographically, philosophically, culturally, and politically from the population building a wall around his new capital. Similarly, Egyptology could be seen as an insular discipline with ancient Egypt presented as an exotic separate entity disconnected from Egypt’s modern realities and the rest of the ancient world. Local communities feel disenfranchised and are to a great extent regarded as a threat to heritage conservation. As in Akhenaton’s case, marginalising communities can lead to regime fall.

To make up for the discipline’s failure to recognise the resonance between Akhenaton’s decisions and his fate and the current affairs of Egyptian archaeology, I have written a postcard to Nefertiti. I have apologised for our modern obsession with her suggested beauty over the contribution that the Amarna period can make to our modern understanding of engaging communities, the impact of marginalisation, and state failure. In approaching objects through the creative means of writing a postcard, I have instantly initiated a personal dialogue with the past. I felt more empowered to write my own story freely, regardless of any prescribed disciplinary measures or boundaries.

Peter Banks

participant; creative writing

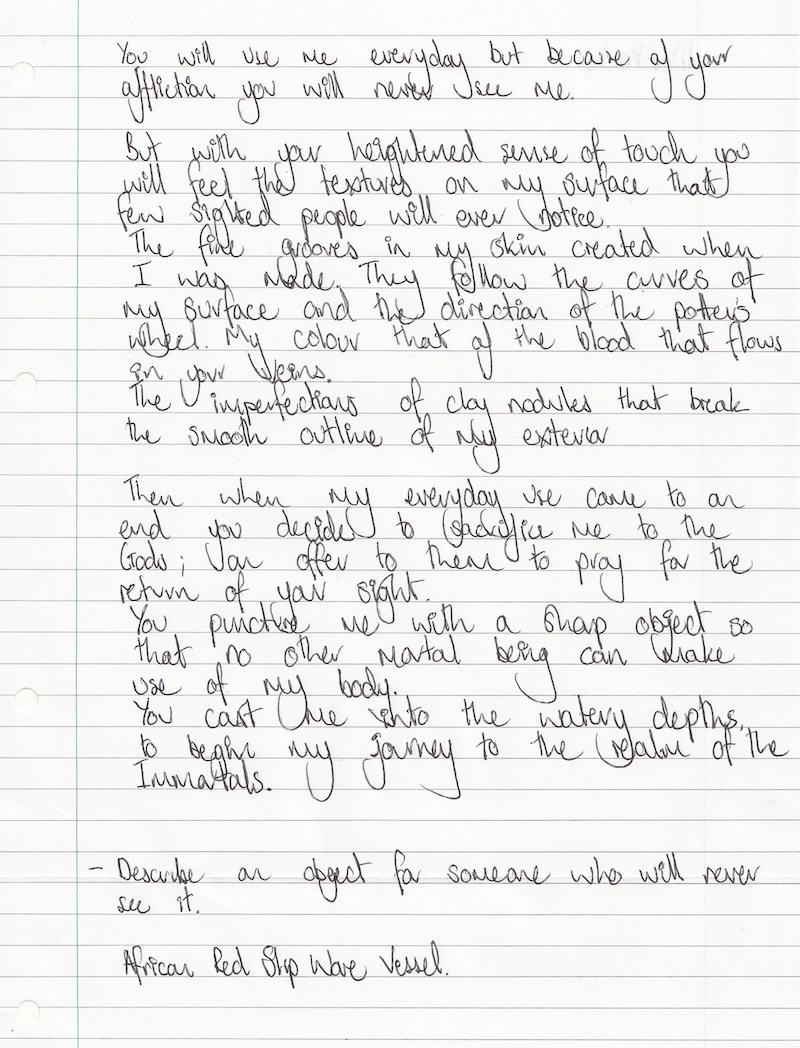

African red-slip ware flagon, Great North Museum, from Carthage (no accession number)

I really enjoyed taking part in the workshop at the Great North Museum. It was great to discover a museum I had previously not known. I think we often forget about local venues and the amazing collections they hold. The curator was enthusiastic and clearly loved the collections in his museum.

I think the project, and the ideas and motivations behind it, were excellent and very worthwhile. I have always enjoyed art and drawing since I was a child, but in recent years I haven’t been able to do as much as I would like. It was an excellent opportunity working with Miranda to reignite and refresh my old drawing skills. I found the photography with Rory very thought provoking. It made me consider the different ways of viewing objects; how something as simple as a shift of lighting angle can really change the way an object looks. Writing about the same object for someone who will never see it, makes you think about how people in the past and from other walks of life may also have different perspectives from myself.

You will use me everyday but because of your affliction you will never see me.

But with your heightened sense of touch you will feel the textures on my surface that few sighted people will ever notice.

The fine grooves in my skin created when I was made. They follow the curves of my surface and the direction of the potter’s wheel. My colour that of the blood that flows in your veins.

The imperfections of clay nodules that break the smooth line of my exterior.

Then when my everyday use came to an end you decide to sacrifice me to the Gods; an offer to them to pray for the return of your sight.

You puncture me with a sharp object so that no other mortal being can make use of my body.

You cast me into the watery depths to being my journey to the realm of the Immortals.

Describe an object for someone who will never see it

African Red Slip Ware Vessel

Antonia Bell

participant; photograph

Ceramic lamps, Great North Museum, from the eastern Mediterranean, 2001.3

I chose these oil lamps because as well as being functional they are also decorative and beautiful. Observations of these objects raised many thought-provoking questions: were these lamps from a temple, commercial or residential building? Could they possibly represent different levels of Roman society? Were they home crafted or made in Roman workshops? What materials were used?

I decided to photograph the lamps as it would show their beauty and functionality to best effect. I positioned them to demonstrate their designs in the best light. The plain black lamp was positioned to show the long spout that would have held the wick; the grey lamp was placed forward and in the centre to show its shape and decoration; while the red lamp was placed to allow the design of olive leaves to be in relief.

Engaging with these objects consolidated my thoughts and perceptions of the artistic and technical sophistication found in Middle Eastern and North African archaeology. From the earliest Mesopotamian settlements through to the later Roman towns and cities, archaeological finds have shown that these cultures were awe inspiring, with beautiful structures and paintings. In addition, they extended that need for beauty to their more functional objects, such as these small but exquisite lamps.

Felix Charteris

MA student helper and participant; creative writing

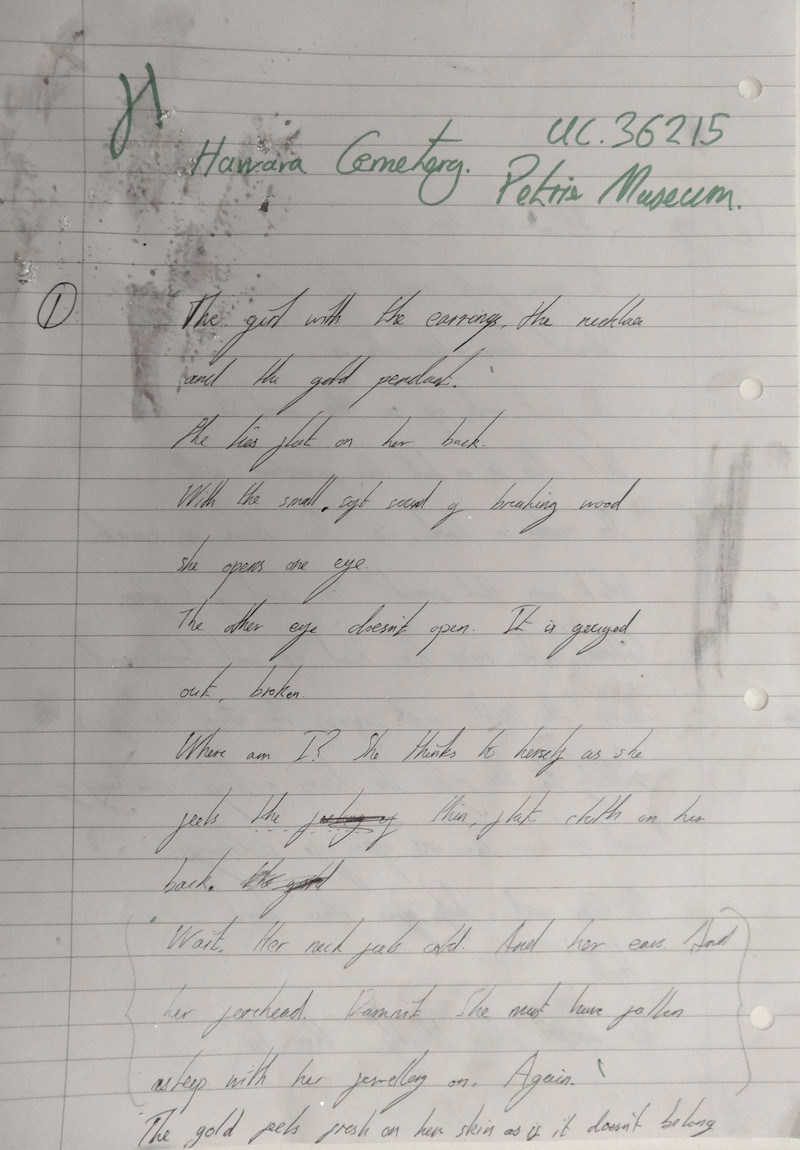

Mummy portrait, Petrie Museum UC36215

This painted portrait upon a broken wooden panel immediately caught my attention. In a row of about five mummy portraits this girl draws the eye. Her delicately painted face is mutilated by damage to the wood, abstracting her right eye to seem as though it was gouged out. This inhuman damage is completely at odds with the delicate blue of the other eye and the beautiful gold leaf pendant and necklace.

Imagining an object woke up in the Petrie Museum in 2016 far from home I was drawn to inhabiting her in the first-person and to pretend that instead of peering down I was, in fact, looking up from this clean, cloth-lined cabinet and through the freshly- and repeatedly-polished glass. Examining this mummy portrait and personifying her for even just one short page reminded me of the humanity behind each object. That this painted likeness still elicits both a voice, a story and a ‘new memory’ is remarkable considering the face, pendant and jewellery depicted in the painting are likely lost forever in all other forms. Engaging the perspective of this object helped reinforce my understanding of their role in museums. Objects are so often removed from their originally-designed intentions and now sit in safety, satisfying the gaze of current museum-goers.

Hawara Cemetery

UC36215

Petrie Museum

The girl with the earrings, the necklace and the gold pendant.

She lies flat on her back

With the small, soft sound of breaking wood

She opens one eye

The other eye doesn’t open. It is gauged out, broken

Where am I? She thinks to herself as she feels the thin, flat cloth on her back.

Wait. Her neck feels cold. And her ears. And her forehead.

Dammit she must have fallen asleep with her jewellery on. Again.

The gold feels fresh on her skin as if it doesn’t belong.

Sarah Ekdawi

collaborator; creative writing

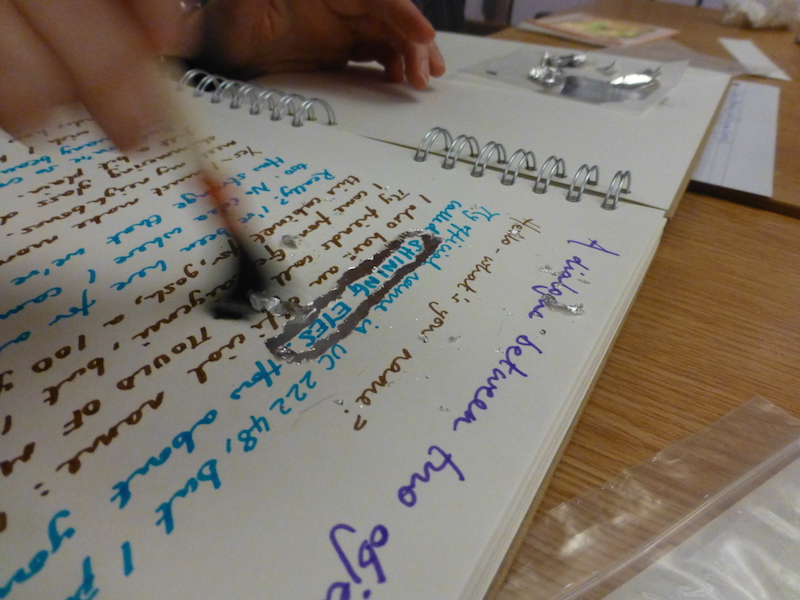

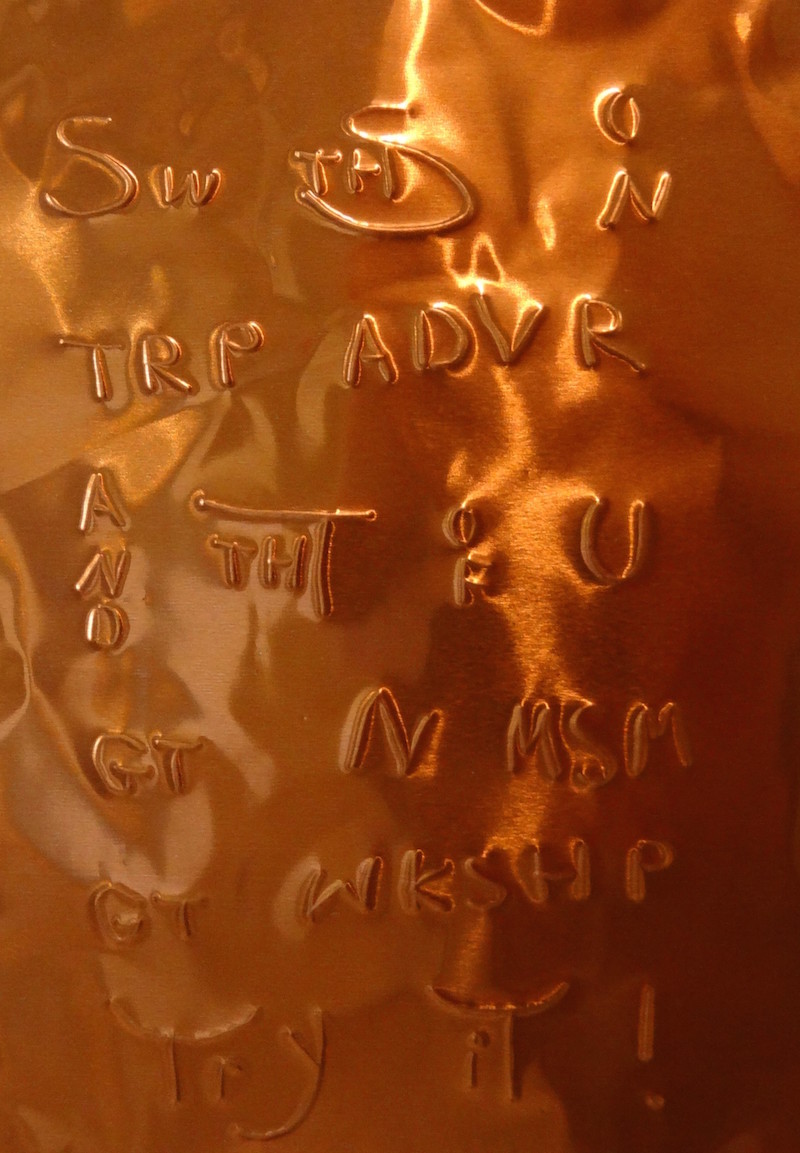

As my previous creative writing courses had been attended exclusively by aspiring writers, I had to re-adjust my practice to sit alongside photography and drawing. It was Zena who came up with the idea of focusing more on the physical creation of writing and using embossing foil as an alternative to the paper and papyrus we had originally provided. This worked well, helping to overcome participants’ fear of the blank page by focusing on the act of writing and its decorative possibilities instead.

I include here my own take on epigraphy and text messaging because new forms of writing are part of my repertoire as an English teacher and also reflect my fascination, as a writer, with the ephemeral (here exemplified by websites, advertising and texting). The project also encouraged me to persist with and try to increase EFL (English as a Foreign Language) student engagement in UK cultural events; three of my students (from Sweden, Germany and Switzerland) attended the London workshops and absolutely loved them.

Zoe Glen

MA student helper and participant; drawing

Fragmentary relief of Sol, Great North Museum, from Vindolanda, 1960.21.A

This Sol hails from a period of Roman rule, but regards us through Hellenistic-influenced eyes from beneath a radiant halo of Eastern iconographic origin; he was found in the northernmost reaches of the Western Empire, but his cultic origins lie in the East. These many factors made this object fascinating to me, as it encapsulates the diversity, movement, and sheer multiculturalism that can be found in any outpost of the Roman Empire. A typical assumption is that the Romans belong wholly to the West, and moved inevitably towards Europe and, above all, Christianity. This project has highlighted for me the inadequacy of this tradition of thought, drawing attention to how the global breadth of Roman influence is still felt and still powerful, including in the Middle East and North Africa. Engaging with objects during this project has taught me to consider far more closely the people behind every artefact – their lives, origins and identities – and to think more critically about the accepted narrative surrounding them. The most invaluable lesson was the expansion and exploration of what ‘Roman’ means to many different people, and how the Roman legacy remains an important and vibrant part of lived identity across the world today.

Jayne Howe

participant; photograph

Glass flask, Great North Museum, from Syria, Israel or Jordan, 1958.54.3

This glass vase caught my eye over other objects as it seemed so delicate. I was intrigued to see how I could use the light to bring out different elements of the texture of the glass, its shape and its colouring. To do this we (photographer, Rory Carnegie and I) experimented with the background, using black or white, which helped to bring out tones like the blue seen in the photograph.

The shape of the small vessel was also attractive to me as I thought it would allow us to catch some excellent shadows and reflections of light. I particularly like the way that the light has hit the vase and allowed us to see the hairline fractures in the glass. We can also see how the glass moves from transparent to opaque in different areas as the speckling on the glass changes, which also adds a beautiful texture. This vase is a charming creation that has stood the test of time and allows us to see the skillset of the contemporary society as well as the fashions that have played into the design of the glass.

Engaging with objects from the Middle East and North Africa has allowed me to view museums as much more interactive spaces. I now visit and think about why the curators have organised what is on display in the way that they did, or why they might have positioned objects a certain way, and used light and angles to accentuate particular aspects of them. It has also helped me to learn more about the objects themselves. Rather than simply reading the captions about the facts of the objects, I can now learn about them from viewing them. This applies to the coins that were brought to the workshop as well as the stonework and the glass. This workshop aided in my studies at University where I studied History. I think it helped me to approach primary sources with more confidence and with a keener eye for detail.

Arthur Laidlaw

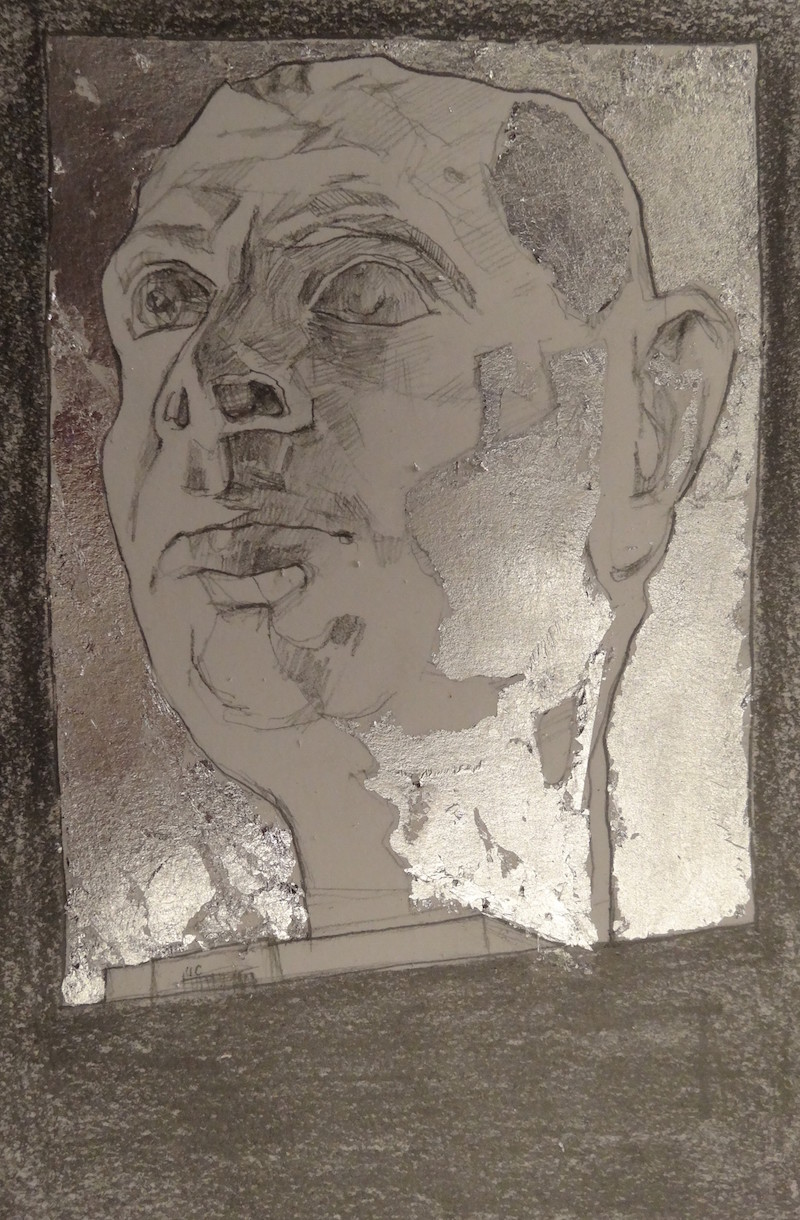

participant; drawing

Limestone male head, Petrie Museum, UC16493

Looking around the Petrie Museum, I was struck by the superficial recognisability of so many of the objects in the collection. I wanted to investigate the idea that our ‘modern’ representatives in politics, law, and business are still chillingly similar to those of two thousand years ago. The white, male, aristocratic figure in my unidentified ‘portrait bust’ looks down his nose at the viewer in just the same way Jeremy Hunt or another member of Theresa May’s cabinet might today. It seems as though nothing has changed since the tyrants of ancient Greece – and perhaps, looking at the slippery leadership politicking that followed the direct democracy of the Brexit referendum last year, nothing has.

Over the last eight years, drawings, photographs, and objects of the Middle East have fundamentally shaped my work as an artist. To prepare for my exhibition, Razed: Syrian Ruins, I first began by re-examining records of Syria and the surrounding countries that I made while travelling in the Middle East in 2009. However, as the work developed and following my day spent at this workshop, the influence of objects in publicly-accessible collections, and the way that those objects were curated, became increasingly important. The paintings were an attempt to reconcile these two worlds: the personal experience of a country, directly shaped by its landscape, culture, and people – and the public experience of a place, indirectly shaped by our retelling of events when we return home, media coverage, political rhetoric and, of course, appropriated objects in museums around the world, robbed of their original context.

Muna Mitchell

participant; photography

Jug, Petrie Museum, UC19402

Amazing, inspiring, engaging! A few words to describe my memories of the day I spent at this workshop at the Petrie Museum. As a non-archaeologist of Middle Eastern origin I was not going to pass up on the opportunity to roam around this stunning collection and create new memories built upon our shared past. I won’t lie: the baklawa was also a pull!

It was such a privilege to spend the day surrounded by these objects that had made their way in many ways to London. The experts were so generous with their time and knowledge; their patience helped me to start to understand the objects in the museum. I did feel completely out of my depth and faintly terrified that others in the group seemed very artistic. What drew me to my object? I think I did what any human does when faced with uncertainty and clung to an object I was familiar with and at least I knew what it was used for! And that little jug was very beautiful! The idea of photographing my object appealed to me as it provided me with a stepping stone to creating a wonderful memory and it freed me up from the worry that my lack of creative ability would spoil my end product.

It is almost inevitable that non-expert visitors to any museum will stroll past displays with very little connection being made in spite of the fact that as a visitor you clearly had the intention of wanting to interact with the museum and its objects. Providing a relaxed and informal environment at the museum enabled us to respond to the objects; teasing out those connections through writing, drawing and photography ensured that we came away with a much deeper understanding and many happy memories.

Aditi Nafde

participant; photograph

African red-slip ware flagon, Great North Museum, from Carthage (no accession number)

I was drawn to this object because of its beautiful, traditional shape and design which seemed instantly recognisable as something from Roman North Africa. I was intrigued, however, by its imperfections. In the process of examining these, I turned the pot around and upside down and its shape became increasingly less recognisable and less familiar. It turned from a pot to a goblet: from a North African Roman object to something that looked to me almost medieval (I am a medievalist). The process of casting deep shadows onto it in the photographs further de-familiarised the object. This prompted me to ask what an object is if it is incomplete or if it is viewed in different ways and how far the way we view an object affects the object itself. The project as a whole has encouraged me to challenge my usual desire to understand objects in their historical contexts and to think more about the effects of their present manifestations.

Andrew Parkin

curator at the Great North Museum

Participating in the RetRo project was a positive and inspiring experience for both staff and visitors at the Great North Museum: Hancock. The workshops provided opportunities to approach Roman objects from the collection in a variety of different ways, some of which were new to those taking part. The project allowed for detailed examination of a range of artefacts from the collection, including pottery, glass vessels, coins and sculpture, and encouraged creative responses to them. It was gratifying to see those taking part challenged to produce written and visual work, such as photographs and drawings, based on this range of material. In addition the presence of experts from different disciplines – photography, visual arts, creative writing and Roman archaeology – inevitably enriched everyone’s understanding of the objects.

From a curatorial perspective the sheer range of responses to a relatively small range of artefacts was very interesting and encouraging. The project opened my eyes to the possibilities of using creative writing or working in different media such as embossing designs on tin foil or using silver leaf to pick out key features of an object in an illustration. The scope for reacting to the collection in diffuse ways has always been there. RetRo served to bring out some new responses and extend our knowledge.

Florence and Louise Thandiwe Wilson

participants; drawing

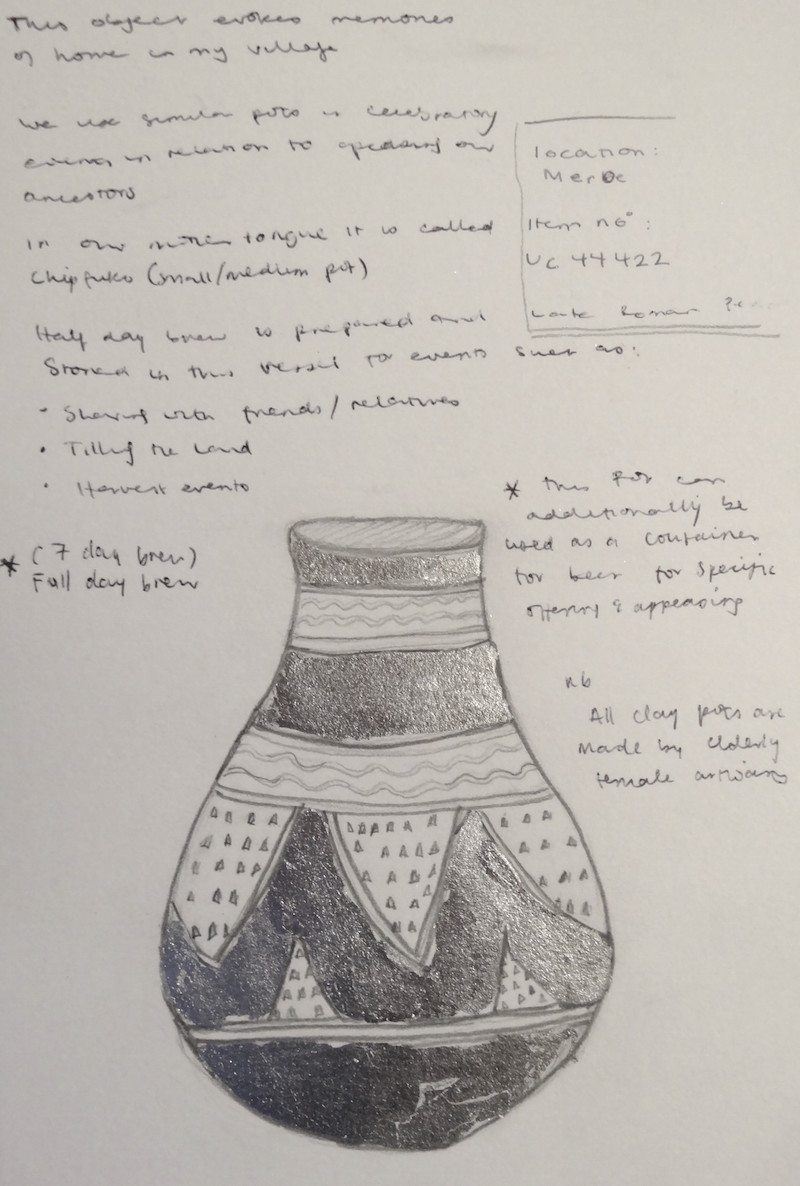

Ceramic flask from Meroe, Petrie Museum, UC44422

Florence: This object evoked memories of our village in Mazvihwa, Zimbabwe. Its appearance and decorative emblems are similar to pots we use. Such clay pots are made by elderly female artisans. In our mother tongue, these vessels are called ‘Chipfuko’. There are two occasions when a mildly fermented drink is stored in these pots. An overnight brew is prepared in these pots to be shared with friends and relatives, this is drunk casually but most often whilst tilling the land. A seven-day brew is stored in these containers for offerings and appeasing our ancestors.

Thandiwe: This experience was an excellent example of reframing heritage. My mother’s (Florence’s) experience of object interaction was entirely different to my own; she had an intimate understanding of traditional knowledge that correlated strikingly with this pottery. By discussing the resemblances, she was able to relate to an ancient object from a different region of Africa through her memories and her cultural practices.

It is vital to facilitate community engagement. Conservation is not simply an aesthetic arrangement; it is a necessity for those who have a profound cultural, historical or emotional investment with collections. Museums and workshops that encourage sustainable relationships by using their exhibits as interactive repositories for communities who have such ties, are invaluable.

Amy Wood

MA student helper; photograph

Key, Petrie Museum, UC7822

During this project, I responded to many objects in different media, but my favourite was a photograph of a key. The key first interested me as it was so easily recognisable and, despite its history and the stories it holds, it is so comparable to modern day life. I wanted to highlight the texture of the key without it feeling heavy and photographing it kept it clean and minimal, showing the wear and the use on the object. Engaging in such a tactile way with objects from the Middle East and North Africa was amazing and experiencing a museum in such a hands-on way provided space to really explore them. Being able to touch and create around the objects made me invest in the objects; I found myself really stopping and examining objects I would have otherwise passed over. This experience did change how I viewed objects from the Middle East and North Africa as I was able to find connections to areas I had previously studied, as well as learning new information about the objects themselves.

Conclusion

Zena Kamash

Although people have responded in a variety of different ways, dependent on a whole range of factors, such as their background and previous knowledge, it is clear from the responses that each person who has written here came away from the workshops with new perspectives on the role that museum collections might play in their lives. As noted in the introduction, these reflections work across several scales from individual object, to collection, to community.

For many people, their object choice was driven by aesthetics and what, at first, seemed familiar or recognisable from the past; objects that people could understand from their present experiences. This was, then, challenged by engaging with the objects in alternative ways – thinking about the feelings of an object, turning it upside down, noticing a hairline crack in a camera flash – which sometimes altered these objects and created a relationship that was different from that first moment of connection. Through these engagements the objects and the new memories created of them, disrupted linear time, creating objects that have both the familiarity and comfort of the present and the challenge and distance of the past. New light, and shade, was cast on the objects for many people, both literally and figuratively, opening up unexpected views and engagements.

“Museum Selfie” by Arthur Laidlaw and Yasmeen al Khoudary, Petrie Museum, UC56003.

Several responses reflect on the nature of museum collections: how those collections came into being, how they are displayed and how visitors respond to them. Notable here is that the workshops gave people an opportunity to pause and to look actively and to carry that experience of pausing and of looking into their current ways of engaging with museum collections, both as visitors and as curators. There is a sense that collections that may have once felt out of reach, now feel more interactive and more accessible.

The importance of people also comes through strongly in the responses. For some this was a realisation that archaeology, superficially the study of objects in the past, is actually a study of people in the past, through their objects. For others, the objects related not just to people in the past, but also to people in the present and future, both personally and politically, provoking memories and emotional responses. Creative engagements with past objects on the RetRo project have shown the potential to empower the disenfranchised, to encourage quiet voices to speak more loudly. We could not have hoped to do more than this in our collaboration.

Acknowledgements

The greatest debt of thanks goes to everyone, specialists and non-specialists, who came and participated in the RetRo project, for sharing their time and their stories. My sincere thanks go to the staff of both museums, who welcomed us into their spaces and let us disrupt their usual schedules. Finally, thanks to Shawn Graham for creating Epoiesen and his help and support in the editing and production process.

Cover Image Andrew Parkin

Masthead Image Zoe Glen