Interactive Mapping of Archaeological Sites in Victoria: First Response

In January of 2012, just as I was starting my second semester in the PhD Archaeology program at UWO, I was introduced to Dr. William J Turkel’s History 9832B: Interactive Exhibit Design (https://williamjturkel.net/teaching/history-9832b-interactive-exhibit-design-winter-2012/) course. Bill as we all called him, was essentially a Mathematician intertwined as a Historian. This guy made history come alive by making, computing and digitizing stuff. His students, including me, drank from the magical well and we were all enthralled with our ability to make, and fail at making (sometimes several times), physical, digital and intellectual connections between the history we study and the user engagement of that history. It is this process that is so vital for history to become knowing. Along with a passion for Twitter, I learned that materiality can take on many forms, narratives and platforms, and in unison, becomes not only a means of making but also consuming knowledge. Transformative would aptly describe Bill, his course and every student’s mindset who have been lucky enough to come before and after.

The themes that now umbrella the exploration and application of making and knowledge creation through making, are transdisciplinary, co-creation, experiential learning, innovation, entrepreneurial spirt and creative impact. What Heckadon et al’s Interactive Mapping does, is manifest these notions into a tight practical cabling (see Wylie 1989; 2002), which punctuates a new era of knowledge creation and dissemination. Although the intention was clearly not a theoretical exploration but one of raw creative ingenuity and wayfaring through the mentorship of Dr. Katherine Cook and PhD candidate Beth Compton, Interactive Mapping provides a glimpse of where we must endeavor to theoretically ground this new methodological framework.

Tim Ingold in particular has introduced making and materiality as key pillars in his livelong pursuit to explain the exploration of the human condition as it relates to culture, society, and the material culture we leave behind from a landscape and object perspective (see Ingold 2007 as well as 2011; 2013). He posits that in the act of making and by manipulating as well as being manipulated by the materials we use to create, we create new knowledge (see Ingold 2007; 2011; 2013). Now Ingold didn’t actually discuss this process from a digital perspective, but he did indicate that we are not immune to the realities that the material we try to shape, whether digital or not, actually reshapes us through the making process. That is to say, transformative by any other word.

Matthew Crawford explores how our attention is intentionally fragmented as we are forced through consumption to snack on multiple sources instead of focusing on a single task (Crawford 2015). Yet Interactive Mapping weaves a convincing narrative through a multimodal approach. It is neither snackable nor singularly focused, but a blending of the two, which consumes and engages the user’s attention - but only at the right time. These are Ecologies of Attention, modes in which we intentionally consume and make-meaning of the world at the moment best suited to our needs (see Crawford 2015 as well as Reilly and Gant 2016).

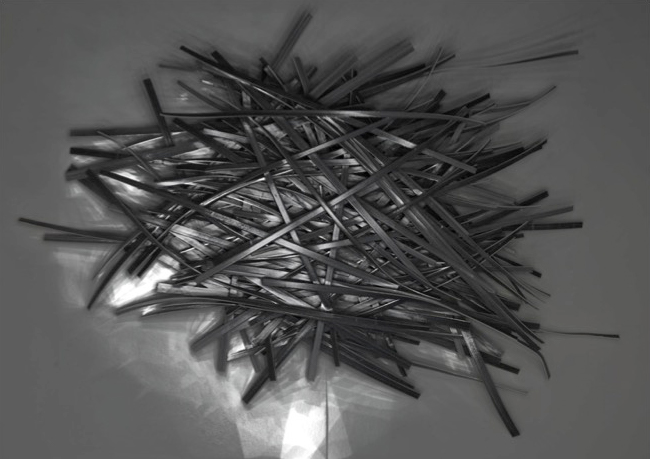

Figure 1 - Linear Phrasing, Gant, S. And Reilly, P. 2016. With permission of the authors.

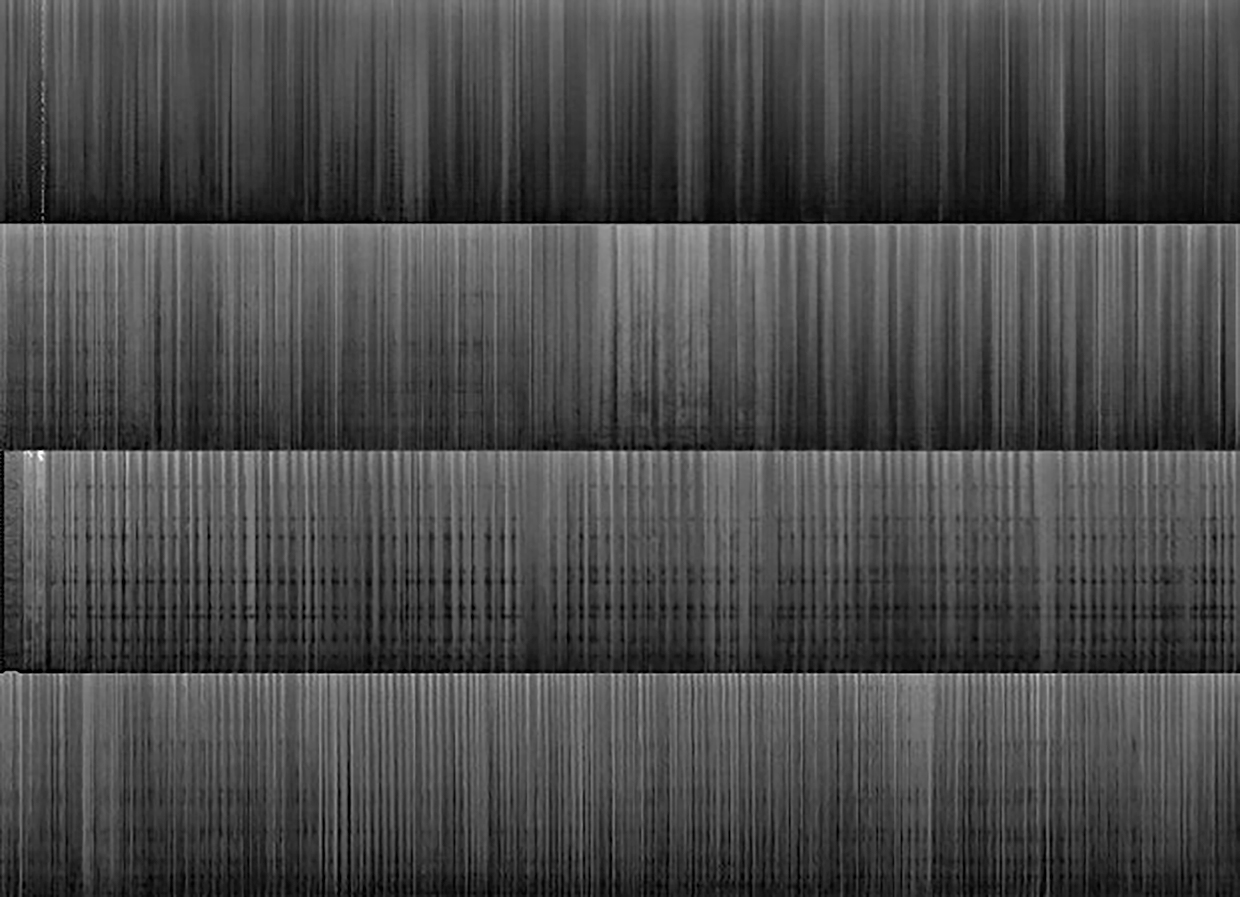

Recently Stefan Gant, Artist and Senior Lecturer in Drawing and New Media at the University of Northampton, and Dr. Paul Reilly (who some consider the "father of virtual archaeology"), presented at the 2016 TAGSoton on their collaborative, co-creation, experiential and innovative art/archaeology project Different expressions of the same mode: apprehending the world through practice, and making a mark (see Reilly and Gant 2016). As with Heckadon et al’s Interactive Mapping, where sound, landscape and materiality played an important role in both the creation and consumption of archaeological meaning-making, Gant explored the materiality of archaeological landscapes by the direct vertical filming and audio recording the real-time excavation of the Iron Age Hillfort of Moel-y-Gaer, Bodfari, Vale of Clwyd (Reilly and Gant 2016). Gant visually and audio recorded every trowel movement as the site was excavated. In a phenomenological symphony of sound and visual textural trowel strokes, the stratigraphy and the materiality of the landscaped dictated the cadence and gestures that was recorded (see Figure 1) (Reilly and Gant 2016). The outcome was not only a Sonic Stratigraphy (see Figure 2), but a "rematerialization" of the act of making archaeology (see Reilly and Gant 2016).

Figure 2 - Sonic Stratigraphy (Series S), Gant, S. 2014-16 (Digital Sonograph. With permission of the author.

Heckadon et al’s Interactive Mapping is transformative because it employs an entrepreneurial approach in facilitating and combining multiple required outcomes into a single substantive deliverable. One would assume that Dr. Cook had the means, opportunity and vision to ensure UVic Anthropology courses could feed into each other. Beth Compton, a research colleague from Western University and Sustainable Archaeology in Ontario, provided the inspiration as Bill Turkel has in the past, to empower students with little or no making experience to explore, fail and eventually construct new knowledge by digital and physical means. Lastly, the Royal BC Museum took a chance and allowed a student inspired, focused and executed pop-up exhibit to be launched under their patronage. An auspicious combination of opportunities which requires foresight, strategic thought and the wishful intention to make it happen.

Whether or not this one small course based project was an experiential opportunity to put into practice, intentional or not, Wylie’s notion of archaeological cabling (see 1989; 2002), it has done so. Wylie suggests that multiple theoretical threads when woven together, create a substantially stronger "cable". Interactive Mapping consists of shades of Ingold for making, materiality and meaning-making. Crawford for intentionality, Reilly and Gant in terms of phenomenology and Turkel for experiential learning among other things. Call it a confluence of ideas, practices and intentions that has now manifested itself into a new mode or cabling of thinking about our archaeological past.

References

Crawford, M.

2015 The World Beyond Your Head: On Becoming an Individual in an Age of Distraction. Penguin: Toronto.

Gant,S. and P. Reilly

2017 Different Expressions Of The Same Mode: A Recent Dialogue Between Archaeological And Contemporary Drawing Practices. JVAP, Taylor and Francis Online (Routledge). https://doi.org/10.1080/14702029.2017.1384974

Ingold, T.

2007 "Materials Against Materiality". Archaeological Dialogues 14.1: 1-16.

2011 Being Alive: Essays on Movement, Knowledge and Description. Routledge: London.

2013 Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. Routledge: London.

Reilly, P., and Stefan Gant

2016 "Different Expressions of the Same Mode: Apprehending the World Through Practice, and Making a Mark". TAGSoton, Theoretical Archaeology Group Conference. Southampton, UK.

Wylie, Alison

1989 "Archaeological Cables and Tackin: The Implications of Practice for Bernstein's Options Beyond Objectivism and Relativism". Philosophy of the Social Sciences 19.1:1.

2002 "Archaeological Cables and Tacking: Beyond Objectivism and Relativism" Thinking from Things: Essays in the Philosophy of Archaeology pp161-167. University of California Press: Berkeley.

Cover Image "Metamorphosis insectorum surinamensium - caption: 'Butterfly and Caterpillar'" British Library

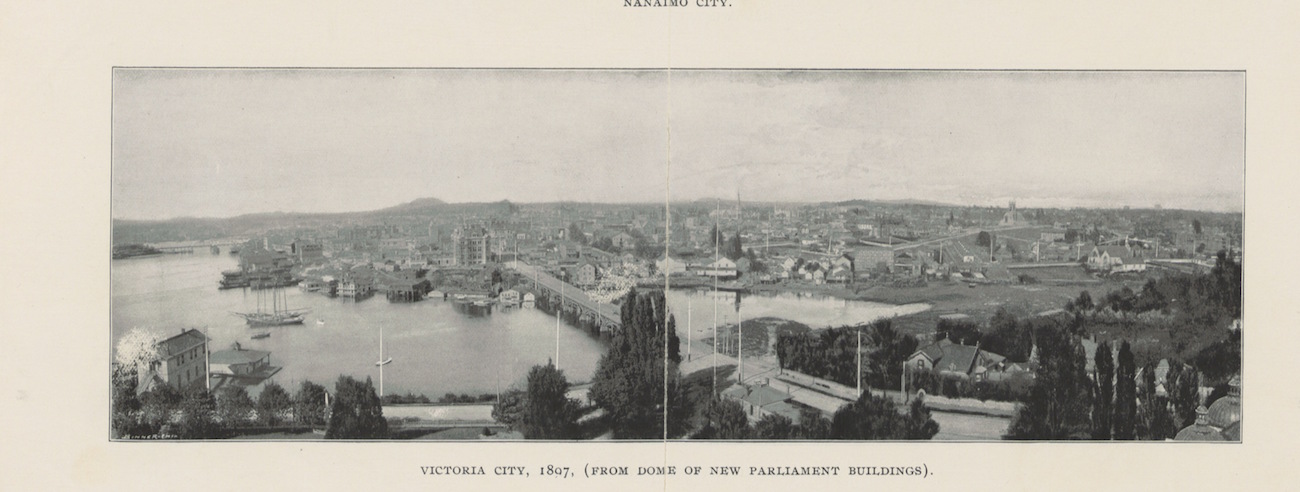

Masthead Image "Victoria City, 1807, (From Dome of New Parliament Buildings). Image taken from page 25 of '(The Year Book of British Columbia Compendium.) Compiled from the Year Book of British Columbia ... To which is added a chapter ... respecting the Canadian Yukon and Northern territory generally'" British Library