Interactive Mapping of Archaeological Sites in Victoria: Second Response

Introduction

The Interactive Mapping of Archaeological Sites in Victoria project is a wonderful example of campus/community collaboration. The extensive collection and welcoming atmosphere of the Royal BC Museum became a space where undergraduate students in heritage and archaeology from the University of Victoria displayed their hard work. Members of the community were on site to benefit from the students' critical thinking and creation of a physical computing project all beautifully wrapped up in the form of a map. Those of us who teach with the ‘maker’ technologies described by Heckadon et al. often seek those exemplary projects to showcase the benefits of hands-on, creative learning, and I think the students here provide us all with such an example. Below I highlight why this project is such a success by focussing on several lessons that the students learned along the way. Although they gloss over these lessons in the midst of describing their creative process, I believe that, in the long run, it will be these lessons that stick with them.

Being Open

The students encountered the benefits of open access and the limitations imposed when knowledge, in this case archaeology records, is kept out of the public eye. The use of Audacity, a free downloadable audio editor, enabled them to include soundscapes (created by their peers for another museum exhibit), and other open source files that they themselves edited, compiled, and added to their map. In researching the histories of the three excavated sites, however, the students found it harder to locate details as these excavations were performed by private firms and therefore are not readily available as publications. Chances are that details provided in these unpublished reports may have greatly enhanced the project, allowing the students to make better claims about their subjects, and to “act as better stewards of cultural heritage” (Kansa & Kansa, 2013), but the students worked around this by thinking carefully about the material that was available to them, and how best to represent this for their audience.

Cultural Sensitivity

Thinking critically about open access is a necessary skill for anyone going into the cultural heritage sector. While having material accessible to them may have helped them gain information that was useful to their project, the students also recognized that there was a need to remain sensitive and aware of the needs of the population whose history was being put on display. As Kim Christen has repeatedly pointed out (2011, 2012), being open is not always desirable for indigenous communities, and the students recognized this when deciding to 3D print materials that represented features of the landscape of each of their three excavations sites instead of attempting to model the archaeological artefacts themselves. Recognizing that culturally sensitive practices mean understanding the needs and desires of Canada’s indigenous communities rather than simply putting their history on display is a lesson from which we can all benefit. Further still, inviting discussion of these decisions regarding the 3D printed objects on their maps with members of the public (children and adults alike) brings these ideas out into the open.

Interface Design

Anyone who has created an installation or display for the public knows that it's not an easy task – designing one that is interactive is even more difficult. Having worked with MakeyMakey’s several times myself, I know exactly the issues of trying to get your audience to do two things at once (touching the star at the bottom of the map with one hand, and reaching out with the other to locate the excavation sites). For the students, design and aesthetics were things they integrated throughout the process: having a map at the center of their exhibit was not enough. They thought carefully about how to best incorporate the copper tape into the map, and had clear spoken instructions about how the map should work (see the video). Skills like this are not easy to acquire in university classes where essay-writing and textbook reading are the main foci. Creating an exhibit that was tested in public gave them the opportunity to envision how these things might work on a larger scale – be it in a museum, a library, or at a conference – and how others can learn from the user-friendly features they designed.

Repurposing

A large part of tinkering is taking something and using it for an unintended purpose. If you take a look at this MakeyMakey video, you’ll see it’s largely used for games and music – as a way to make conductive items (fruit, metal, humans) into keys on a keyboard. The students took this gaming device and repurposed it, making it a part of a larger educational display. By hiding the MakeyMakey behind their map, they also changed the focus of what usually happens when you use this tool (inevitably, people pick up the micro-processor to see how it works and want to connect it to everything around them), and made the information piece – the map itself – into the platform for interaction. They also repurposed the map: turning it from a way-finding tool to a multi-sensory experience for learning about archaeology. This type of out-of-the-box thinking helps to hold the public’s imagination (Ciolfi & Bannon, 2002), and these students did all of this in a few weeks, with a tiny budget and some inspiration.

Learning to Fail

In any hands-on, creative project, there needs to be room to fail. Failure is rarely rewarded in academic settings, and this is unfortunate because it's usually when the learning happens. Hackadon et. al. noted that they had hoped to include a series of lights that would showcase the excavation sites as the recorded information and soundscape about them was being played. They tried several times – both with MakeyMakey (finding out this tool’s limitations) and with copper tape and batteries (which they believed was not secure enough for them to base altering the map on), and finally decided that they would do without. They failed to get a part of the map to work the way they intended, but they learned so much in the process: simple circuitry, conductivity, and their desire to put interactivity and aesthetics above an aspect of their project which might not work. They accepted this failure and moved on, but still decided to write it up as part of their process. In doing so, they didn’t just fail, they learned to fail in a way that demonstrated to themselves and others the benefits of trial and error.

Conclusion

If you're lucky, you've experienced it: that one lesson that you won’t forget. Whether it was in kindergarten, high school, college, university, or just out in the world, this lesson stood out because you were allowed to experiment. You set yourself a goal, saw it through, and taught yourself many things along the way. And perhaps you were given an opportunity to present your work so that you experienced the impact made by your project. Those of us that are privileged enough to go on to teach others should all be aiming for our lessons to be the one, and, as Hackadon et al. demonstrate, Katherine and Beth succeeded. Such fortunate students, such lucky instructors.

Works Cited

Christen, K. "Does Information Really Want to be Free ? Indigenous Knowledge Systems and the Question of Openness." International Journal of Communication, vol. 6, 2012, pp. 2870–2893. Retrieved from: http://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/1618

Christen, K. “Opening Archives: Respectful Repatriation.” The American Archivistvol.74, Spring/Summer 2011, pp. 185–210. Retrieved from: http://digitalnais.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/Kimberly_Opening_Archives.pdf

Ciolfi, Luigina and Liam J. Bannon. “Designing Interactive Museum Exhibits : Enhancing Visitor Curiosity through Augmented Artefacts.” in ECCE11 - Eleventh European Conference on Cognitive Ergonomics. Catania, Italy, 2002. Retrieved from: http://echo.iat.sfu.ca/library/ciolfi_museum_exhibits_augmented_artefacts.pdf

Kansa, E. C. & Kansa, S. W. "We All Know That a 14 Is a Sheep: Data Publication and Professionalism in Archaeological Communication." Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies , vol. 1 no. 1, 2013, pp. 88-97. Retrieved from: Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.1.1.0088

Cover Image "Image taken from page 84 of 'A Text-book of Coal-Mining ... With ... illustrations'" British Library

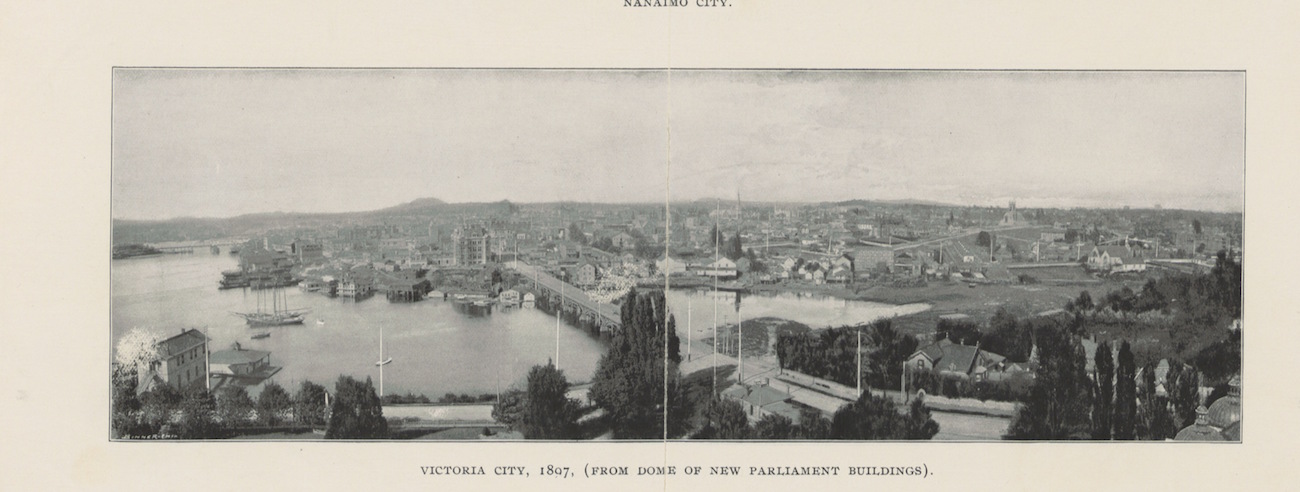

Masthead Image "Victoria City, 1807, (From Dome of New Parliament Buildings). Image taken from page 25 of '(The Year Book of British Columbia Compendium.) Compiled from the Year Book of British Columbia ... To which is added a chapter ... respecting the Canadian Yukon and Northern territory generally'" British Library