Contains Scenes of a Graphic Nature: Sympathy for the Devil. Second Response

Our Voices, Their Voices

The past decade has seen a reinvigoration of creative mediums for telling the past, and more and more investment by historical/archaeological researchers in creating or contributing to those narratives. The current explosion of historically-based comics and graphic novels find thoughtful companions in videogames, film and television, art exhibits and public installations, interactive and collaborative museums and heritage experiences, and more. Following a great deal of trailblazing and risk-taking (particularly given the intense anxieties surrounding the traditional publish or perish model of publishing in academia), artist-historians and –archaeologists (or collaborations between scholars and artists) are finally beginning to benefit from shifting values, including new platforms for publishing, licensing and sharing these out-of-the-box but incredibly powerful contributions to our understandings of the past (not least of which being this very journal, Epoiesen).

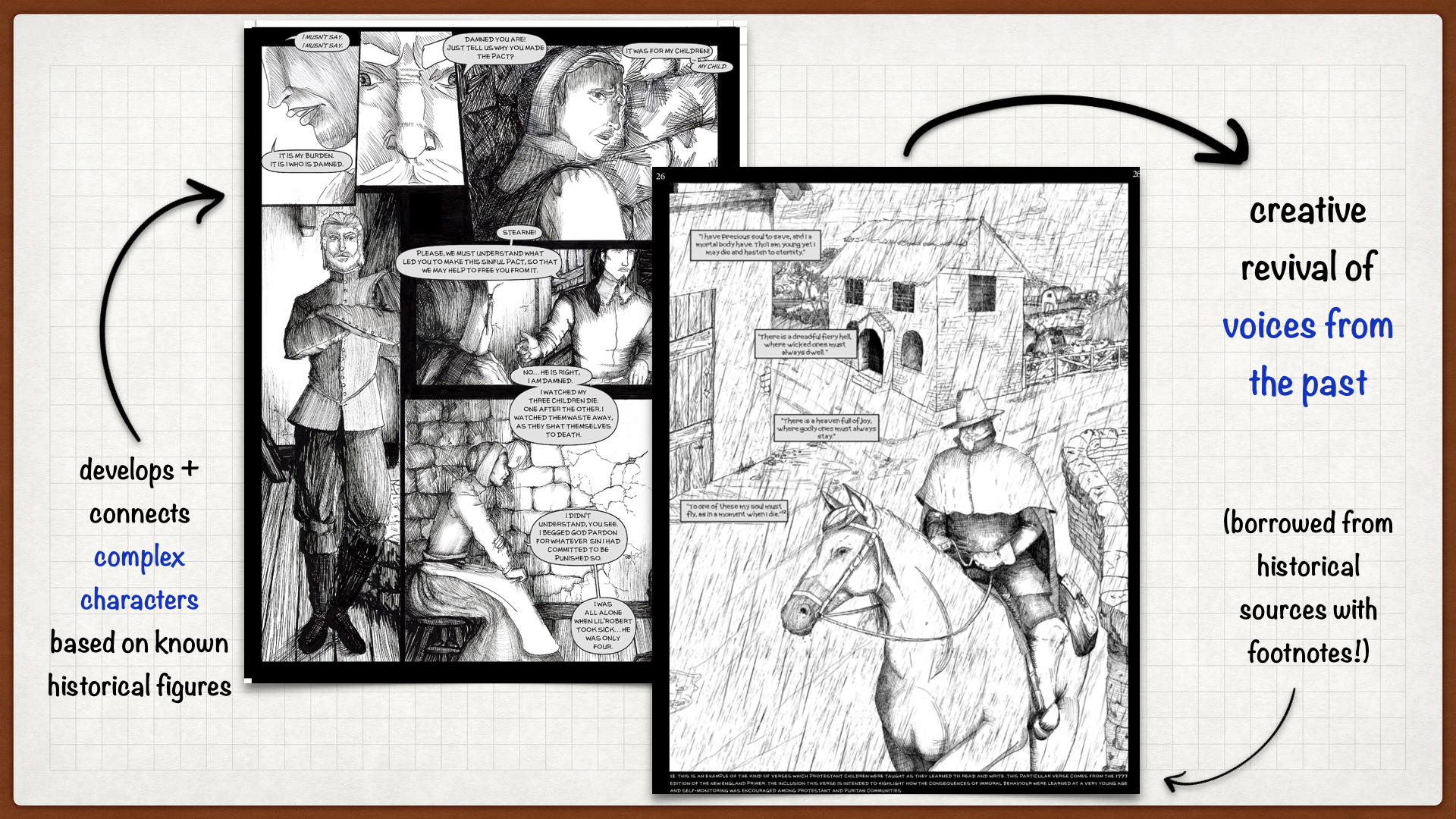

Laurel Rowe’s Sympathy for the Devil graphic novel, accompanied by the reflective tone of her article Contains Scenes of a Graphic Nature, then, perfectly embodies this shift in historical engagement, demonstrating careful and thoughtful weaving together of historical sources, figures, and settings, but also contemporary politics and practices in choosing whose voices we showcase, why and how. Recognizing that history is storytelling – and therefore that historians (and I would add archaeologists) are essentially authors – we can begin to reflect on the ways in which we are playing active roles in constructing narratives, characters, plots and outcomes through their interpretation and communication processes, including but not limited to writing.

Rowe, Sympathy for the Devil. Annotations by K. Cook.

This framing of history and archaeology as storytelling opens the door to a further layer of creative practice: how do we interweave the threads of past stories with our own, to better reflect and communicate our processes and our role in shaping those narratives we construct? To build on Gray’s First Response to Rowe’s article/graphic novel, considering the tensions between truth, construction, and representations, but also recognizing the complexity of discourses on subjectivity and ontologies, how do we make our processes not only more transparent for public consumption, but also do so without undermining the value of our work (an admittedly widespread fear)?

Our Perception, Public Perception

In every story, Rowe (2018) thoughtfully notes, there is an interplay “between the reader’s interpretation, storyteller’s agenda, and narrative”, and this interplay presents opportunities for playful and unconventional engagements. However, the position and perception of disciplines studying the past is facing considerable challenges today. It is not a coincidence that personal genetics tests, marketed as a route to your own heritage, and science-forward analyses of past environmental and health data are finding more public traction than oral histories, traditional ecological knowledge, and ‘other ways of knowing’. The politics of objectivity, also deeply connected to the emerging era of “fake news” and “alt-facts”, are leading to huge levels of paranoia that seem to run counter to the art and subjectivity of storytelling in history and archaeology.

The explosive controversy over BBC’s Life in Roman Britain in the summer of 2017 is particularly interesting for considering the connection between visual storytelling, in this case a children’s animated TV series, and the evidence, politics and perceptions of the past. After the short cartoon was released, featuring an ethnically-diverse (read: not white) family in Roman Britain, social media erupted with critiques about how the story was not representative of this period in British history. Historians, including Mary Beard, who leapt to the defense of the narrative, citing archaeological and historical evidence, received backlash and death threats in return. The ensuing debates came to be centered around the value of ancientDNA evidence, which has so far uncovered only limited evidence of an ethnically-diverse Roman Britain, and historical sources, which do confirm at least some ethnic diversity in this peripheral zone of the Roman empire, but also importantly the role of historians and the impact of contemporary politics. Widely viewed as the proliferation of political correctness, and the conflation of historical accuracy with representativeness (e.g. ‘if only a few Romans in Britain weren’t white, why bother showing them – shouldn’t we be depicting the majority?’), the debate about BBC’s Life in Roman Britain, now archived in expressive tweets and Facebook posts, reveal a great public distrust of the subjectivity of historical research and storytelling and political paranoia (not detached from more widespread political distrust today).

Is part of the problem in public perceptions of studies of the past, then, that we have yet to fully communicate or sell the public on the value of interpretation, subjectivity, reflexivity? And does the age of fake news and related emphasis on critical analysis of media open the door for greater interweaving of stories, evidence, and our methodologies/decision-making as researchers to allow for better public evaluation of our work (and in turn, the work of pseudoarchaeologists, etc.)? Storytelling is not a new part of history and archaeology; we have been narrating the past for as long as we have been interested in the past (aka since time immemorial). However, we are clearly not yet masters of this craft; further refinement and creative use of voice and point of view, in relation to time and structure, of the stories we tell is critical to the future position of studies of the past (see also Joyce 2002, Lamarque 1990).

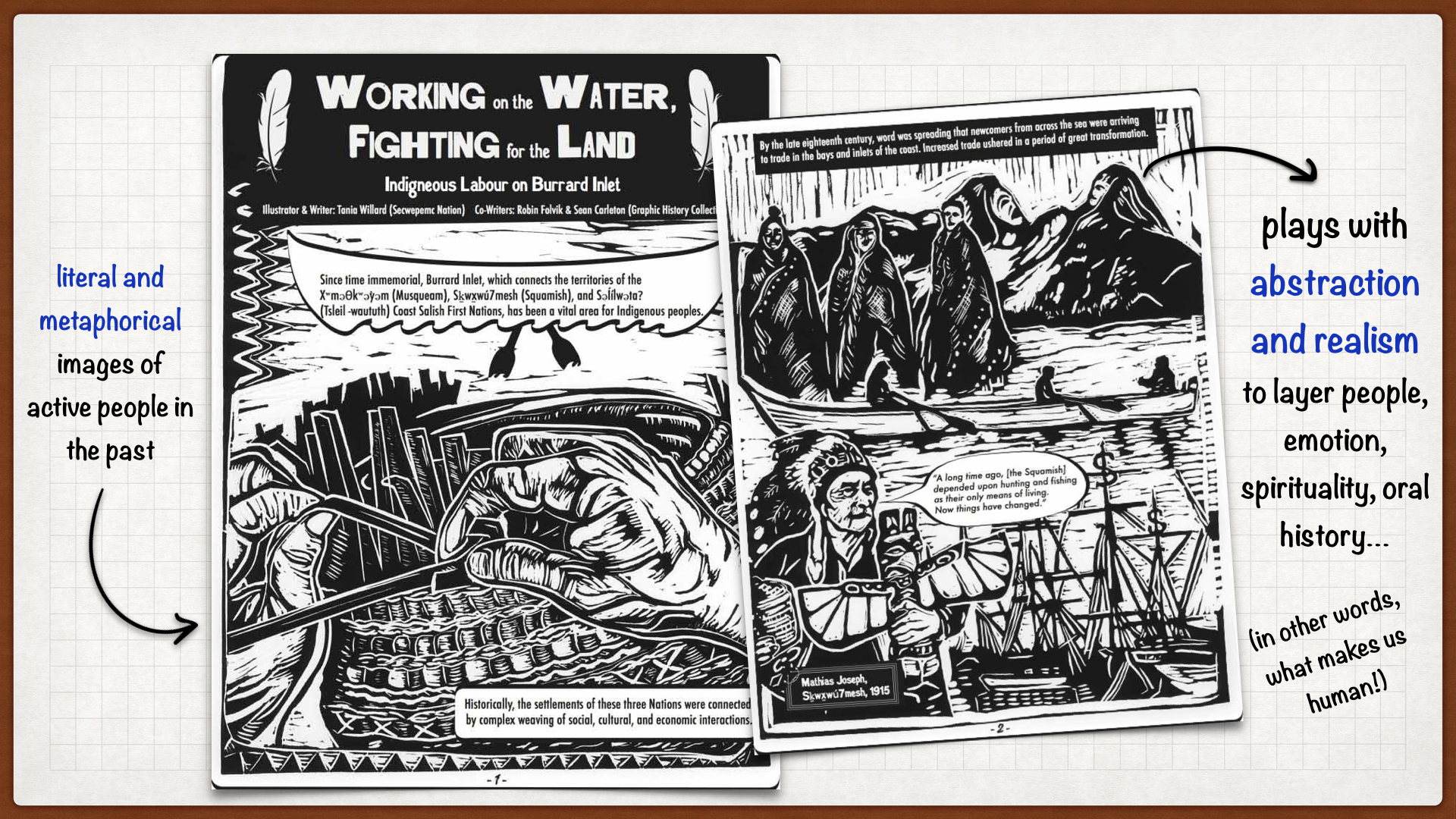

Tania Willard, Robin Folvik, and Sean Carleton, "Working on the Water, Fighting for the Land: Indigenous Labour on Burrard Inlet" in Drawn to Change: Graphic Histories of Working-Class Struggle (Toronto: Between the Lines, 2016), 31-32. Used with permission. Annotations by K. Cook.

What could their voices look like?

In archaeology and history, we have long taken the image of people for granted, including their role as active agents in the stories that we tell about the past. From book illustrations and to museum dioramas, representations of people in the past have been heavily critiqued for the problematic frameworks and limited visual vocabulary (see for instance Gifford-Gonzalez 1993, Moser 1998). This has stimulated a period of experimentation that has pushed forward visual representations of the past to not only draw people into existence, but has challenged us to give them voices, agency, and emotion (and ultimately, humanity). From Colleen Morgan’s critical but often playful use avatars, gifs, and other digital media to the Graphic History Collective’s collaborative poster series highlighting “the histories of Indigenous peoples, women, workers, and other oppressed people who are often overlooked or marginalized in mainstream historical accounts”, there is an ever-growing library of visual storytelling, infused with compelling people and powerful voices.

The resurging popularity of graphic novels and comics has been seized by scholars and researchers, such as archaeology-artists like Hannah Kate Sackett and John G. Swogger have been particularly prolific in their production of scholarship-driven comics. Like Rowe’s Sympathy for the Devil, the graphic novel/comic medium is proving to be extremely effective for public consumption of the past (see also Barletta and Lo Manto 2018). The flexibility of length, colour and black and white formats, and, most recently, digital publication provides seemingly infinite applications of visual storytelling for a range of price points, audiences and motivations. More importantly, the seamless integration of realism and abstraction allows authors/artists to play with metaphor, analogy and symbolism to develop a range of historical characters, with depth of emotion and experience, to highlight the diversity of perspectives, voices and agency of people in the past.

One of the most evocative uses of visual storytelling to bring people to life is the Working on the Water, Fighting for the Land: Indigenous Labour on Burrard Inlet, illustrated and written by Tania Willard (Secwepemc Nation) with co-writers Robin Folvik and Sean Carleton (from the Graphic History Collective). The layers of imagery carefully crafted into this story are so complex and detailed that I have to credit the students of a recent course on Storytelling in Archaeology that I taught at the University of Victory for helping me to recognize all the ways in which metaphors, analogies, symbolism and other visual nods to culture, oral history, emotion, spirituality, and humanity are seemingly built into every square millimeter of this comic to present an all-consuming and powerful narrative of the past. From anthropomorphized mountains and European ship masts that morph into dollar signs, objects and landscapes, and people themselves, are intricately woven together to tell an extremely complex and important story in a way that is meaningful and thought-provoking. At its core are people that live, breath, and transform the story (and history more broadly). The communication of so very much with so very little text is masterful and to this day fills me with deep reverence.

What could our voices look like?

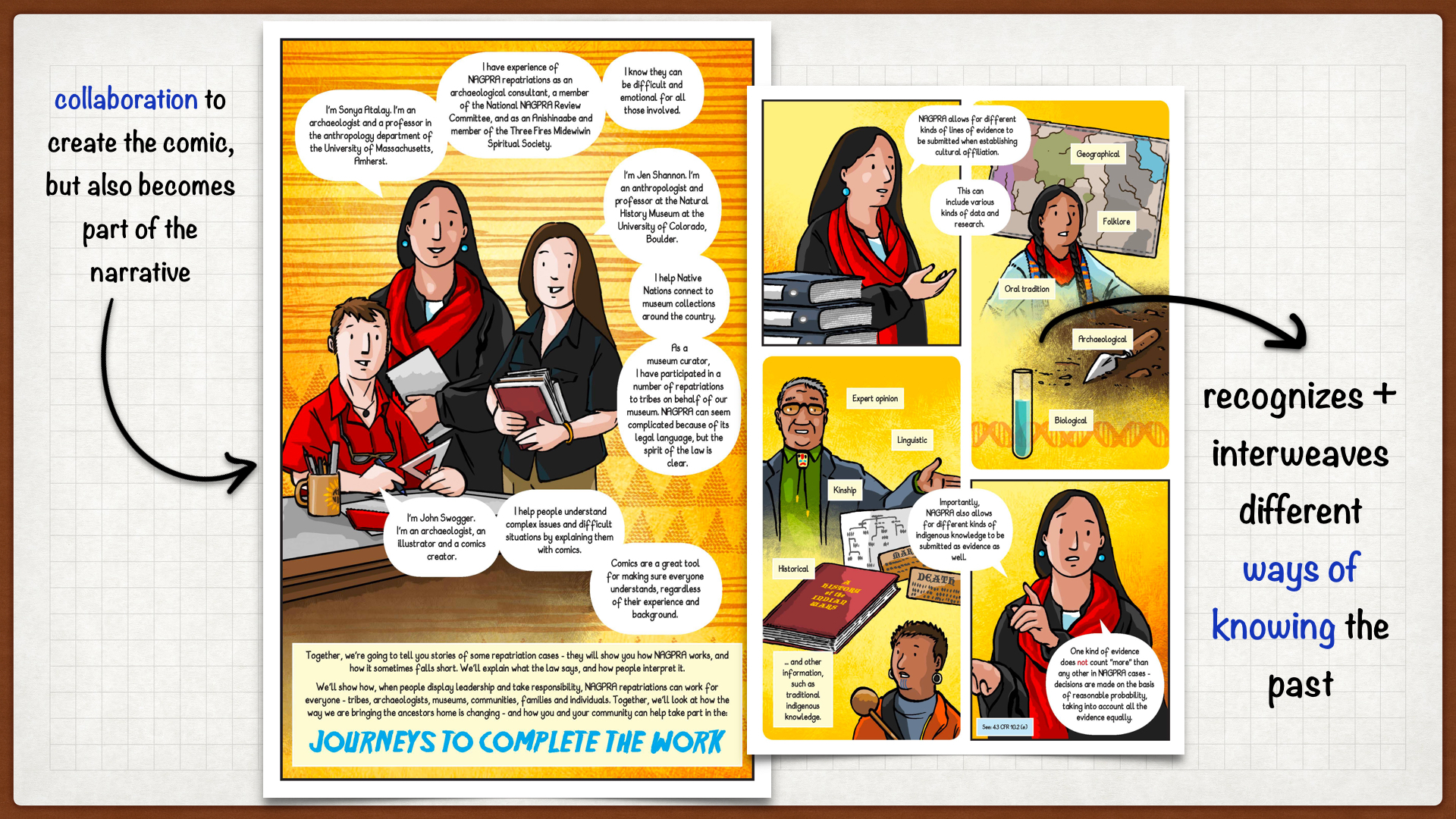

Perhaps the most valuable way to think about presenting our own voices in graphic formats is to conceptualise is a visual rendition of Sonya Atalay’s ‘knowledge braiding’, the active interweaving of many truths in interpreting and presenting the past (Atalay 2012, 2016:55). And in fact the comic book Journeys to Complete the Work undertaken by Sonya Atalay, Jen Shannon, and John G. Swogger with Shannon Martin, William Johnson, Sydney Martin, George Martin, and the Ziibiwing Center of Anishinabe Culture and Lifeways does just that – weaves together contemporary and past stories, people, and methodologies into an engaging story about the complexities of repatriation, law, and collaboration from diverse perspectives. The transparency of heritage and archaeological practice, mediated by different points of view and voices visualized in this comic, transforms the mainstream (colonial) narrative of the past. The story, which could be a very dry, objective overview of heritage law, is given life through the representation of emotion, trauma, voice, and power. It uses politics, emotions and conflicts to move the story forward and better explain why this issue is so important today but also why the multiple lines of evidence can be so complex to work with.

Atalay et al. 2017, Journeys to Complete the Work. Shared and modified under CC-BY-NC-SA. Annotations by K. Cook.

The interlacing of past and present, history and historian will also be explored in the upcoming graphic novel Wake: The Hidden History of Women-led Slave Revolts by Dr. Rebecca Hall, with art by Hugo Martinez. In a recent (and very successful) crowdfunding campaign, Hall noted that women in slave revolts “was the point of [her] academic work. The work has been published, it received a number of awards, but it is buried in academia… The point of this graphic novel is to get this story out to people. It’s too important to just be hidden in a history book that only graduate students will read.” Notably, the project uses the craft of graphic noveling to tell invisible and underrepresented stories of women in the past but also to tell her own story in looking for those stories, bending and repeating panels or sections of panels to draw connections and overlap the contemporary with multiple layers of the past. The example panels that have been released so far demonstrate incredible potential for drawing audiences into the complexity of the relationship between our voices as researchers, the voices of people in the past, and mainstream heritage. Interestingly, the crowdfunding campaign itself, and the ensuing media attention, has in many ways also become a platform for highlighting the realities of historical research, academic structures and public engagement, through Hall’s openness about the debt, lack of support and need for another fulltime job in order to support this incredibly significant work. The project’s perception-bending impact, then, is twofold: 1) drawing attention to the strength and contribution of women in slave revolts, which often go unrecorded/unreported; and 2) shifting public understandings of what it is to be a historian today (particularly showing that historians are not irrelevant figures closed up in mahogany clad offices with cushy jobs but rather subject to widespread problems with job security/stability, equity, and inclusivity).

And perhaps this is the greatest contribution that creative engagements with the past allow for: the flexible interplay of past(s) with the present, the transparent entanglement of the voices of others and with our own voices, and the annotation of captivating narratives with evidence and methodology. Where the linearity of traditional text-based writings limits the fluidity and productive abstraction of research, we can experiment with visualizations, media, and other forms of creative storytelling to colour outside the boxes of mainstream history and challenge our own notions of the past, but also those of diverse public audiences.

References Cited

Atalay, Sonya (2012). Community-Based Archaeology: Research with, by and for Indigenous and Local Communities. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

Atalay, Sonya (2016). Engaging Archaeology: Positivism, Objectivity, and Rigor in Activist Archaeology. In Transforming Archaeology: Activist Practices and Prospects, edited by Sonya Atalay, Lee Rains Clauss, Randall H. McGuire, and John R. Welch, pp. 45-60. New York: Routledge.

Atalay, Sonya, Jen Shannon, and John G. Swogger (2017). Journeys to Complete the Work. Stories about repatriations and changing the way we bring Native American ancestors home. https://blogs.umass.edu/satalay/repatriation-comic/

Barletta, Emiliano and Alessio Lo Manto (2018). Archaeology & Comics. Ex Novo: Journal of Archaeology. http://archaeologiaexnovo.org/2016/archaeologycomics/

Gifford-Gonzalez, Diane (1993). You Can Hide, but You Can’t Run: Representations of Women’s Work in Illustrations of Paleolithic Life. Visual Anthropology Review 9(1): 3-21.

Tania Willard, Robin Folvik, and Sean Carleton, "Working on the Water, Fighting for the Land: Indigenous Labour on Burrard Inlet" in Drawn to Change: Graphic Histories of Working-Class Struggle Toronto: Between the Lines, 2016.

Gray, Brenna. 2018. “Contains Scenes of a Graphic Nature: Sympathy for the Devil. First Response”. Epoiesen. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22215/epoiesen/2018.8

Joyce, Rosemary A. (2002). The Languages of Archaeology: Dialogue, Narrative and Writing. Blackwell.

Lamarque, Peter Vaudreuil (1990). Narrative and Invention: the Limits of Fictionality. In Narrative in Culture: the Uses of Storytelling in the Sciences, Philosophy and Literature, edited by C. Nash, pp. 131-153. Routledge.

Moser, Stephanie (1998). Ancestral Images: The Iconography of Human Evolution. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Rowe, Laurel. 2018. “Contains Scenes of a Graphic Nature: Sympathy for the Devil”. Epoiesen. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22215/epoiesen/2018.5

Cover Image "Image taken from page 10 of 'Lullabies of Many Lands collected and rendered into English verse by A. Strettell. With ... illustrations, etc'" British Library

Masthead Image Rowe, Sympathy for the Devil, pg 4