Assemblage Theory: Recording the Archaeological Record

Assemblage theory is an approach to systems analysis that emphasizes fluidity, exchangeability, and multiple functionalities. Assemblages appear to be functioning as a whole, but are actually coherent bits of a system whose components can be “yanked” out of one system, “plugged” into another, and still work. As such, assemblages characteristically have functional capacities but do not have a function—that is, they are not designed to only do one thing.

—Texas Theory Wiki [http://wikis.la.utexas.edu/theory/page/assemblage-theory]

An assemblage is an archaeological term meaning a group of different artifacts found in association with one another, that is, in the same context. An assemblage is a group of artifacts recurring together at a particular time and place, and representing the sum of human activities.

—Colin Renfrew and Paul Bahn. 2008. Archaeology: Theories, Methods, and Practice. Thames & Hudson.

As an archaeologist, I constantly deal with the archaeological record, the body of physical evidence about the past. As a musician, I wanted to create my own archaeological record, one that adhered to archaeological rules/definitions. The resulting effort is a 41-minute, 8-song set of electronic dance music: Assemblage Theory, under my recording name of “Cyphernaut.”

I took the name of the record from the eponymous book by Manuel DeLanda. [1] Published in 2016, DeLanda’s book fuses the work of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari with a new theory of social complexity. Simplified, society is made up of individuals, and even though people come and go, society persists through the grace of interchangeable parts. As seen in the first definition above, society does not function as a whole but is rather a system of harmonious units.

In archaeology, we talk about “assemblages”, groups of related, contemporaneous artifacts found together, that when interpreted as a whole are able to convey information, a narrative, or in the case of my music, a song, and a collection of related songs. If I am excavating the contents of a well, I first know the purpose of the well (a built space for water-gathering). I know that things I retrieve from the well were either intentionally deposited or accidentally dropped. The Law of Superposition states that things on top are more recent than things underneath in a given context, so that can help us determine what artifacts go with what from the well, albeit if there was still water in the well when objects ended up there, these artifacts could mingle together, ultimately settling near each other, providing an odd puzzle of artifacts to try to disentangle. Music is like this: we have a general container, which could be either a song or an album or a genre inside of which is a wealth of complex data ranging from time signatures and keys to instrumentations to arrangements, musical modes, and lyrical content.

Working from these two definitions of “assemblage”, I set myself some parameters prior to creating my first songs. I had done this before on my Punk Archaeology record, limiting myself to a maximum of three hours from a song’s inception to its final mix, and limiting myself to three takes for each instrument used on any given song. The result was very raw, very rough, and very Punk. For Assemblage Theory, I settled on a style (electronic/intelligent dance music, or EDM/IDM), and limited myself to royalty-free, public domain found-sounds natively recorded in a certain key and beats-per-minute (BPM). These limits served very much as research questions: when you excavate, you can either conduct “total excavation” or you can perhaps use your time and finite resources more wisely by conducting your archaeological investigation based on a set of queries or hypotheses.

Just as an archaeologist doesn’t create the context being excavated, I did not play a single note on the “archaeological record.” Instead, I discovered artifacts (sounds), piecing them together to create a narrative out of the assemblage of artifacts (songs), at last creating a sequence of assemblages within a site (the album). The challenge was in identifying sounds and then figuring out how they would go together to create something logical (if not listenable). One thing to bear in mind is that these found-sounds were created originally to go with other songs. For my project, I was pulling various sounds from disparate sources to create new songs of my own, thus following the Deleuzeian definition of “assemblage theory.” The sounds are interchangeable but serve the same function as individual building blocks to a cohesive whole of a song.

Some pottery-rich excavations (including two that I have worked on) include pot-menders and conservators who are able to, with great patience and care, piece together sherds—sometimes found meters apart—to create the original vessel. My job as the producer in the studio was to do the same thing with the sounds I’d found, but in this case, taking sherds from many different pots to create an entirely new vessel. The pieces served the same function—to create a pot—and the resulting creation also served the same function as the original vessel (to hold liquid), yet the outcome was wholly outside of the imagination of the pot’s original maker. I would love to be able to find the creators of the original sounds I’d found and then play back my song, which uses their creations in an unanticipated way. This is a weird kind of archaeology then, begging the question of whether or not our archaeological interpretations based on found evidence are actually (or partially) correct. Just because we can use artifacts from the same context to tell a logical story does not mean that the story we tell is correct.

In the case of my music, I knew I was making something new based on older material, telling a new story from disparate elements sharing a key and BPM. In hindsight, I created my own assemblages from which I could create new songs as opposed to working with sounds from one song found in some long-abandoned studio, piecing them back together to make something approximating what the original artist intended. What I have made, however, is perhaps reflective of how societies are made if one follows DeLandas’ assemblage theory thesis. Societies and their cities are made up of individual, interchangeable components that share similar characteristics yet are also different from one another when viewed at a fine grain. Together this mix of old and young, indigenous and colonist, combine to make their habitable space evolve. New York City, where I work, is always under construction yet is itself very old. New people arrive every day, and the city persists and changes, yet always maintains a distinct New York City feel. When I consider my songs in this context, what I am doing is archaeological, trending more towards an evolution from old to new, combining things in complex, unintended ways, to arrive at something recognizable yet never-before-heard. Perhaps I have stopped being an archaeologist and am instead an archaeological force. The end result of this song, and this collection of songs, is itself an artifact, and perhaps even a site. Deconstructing it into its individual parts (tracks) can lead back to various sources, a melting pot of sound.

How to Make A Sonic Assemblage

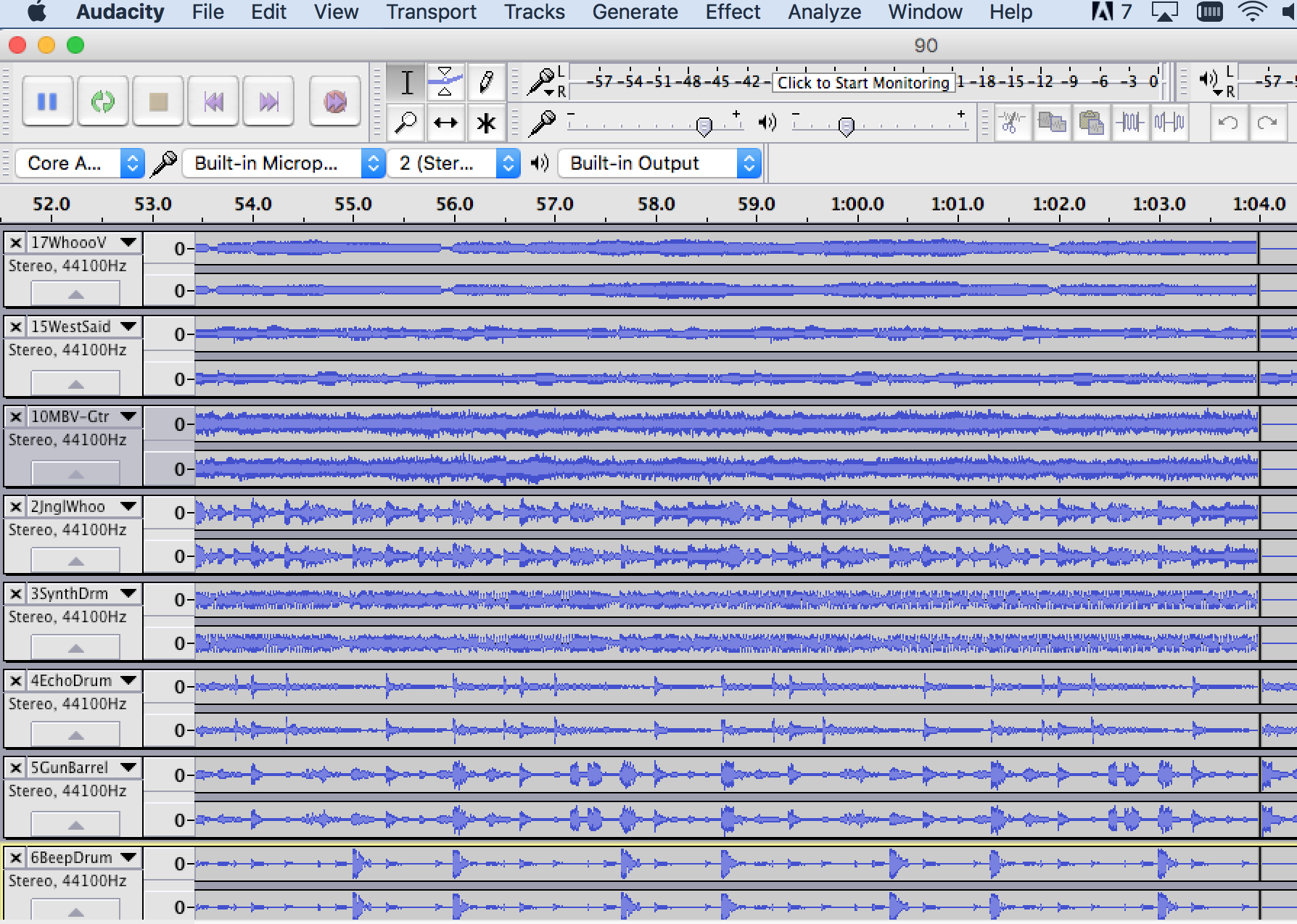

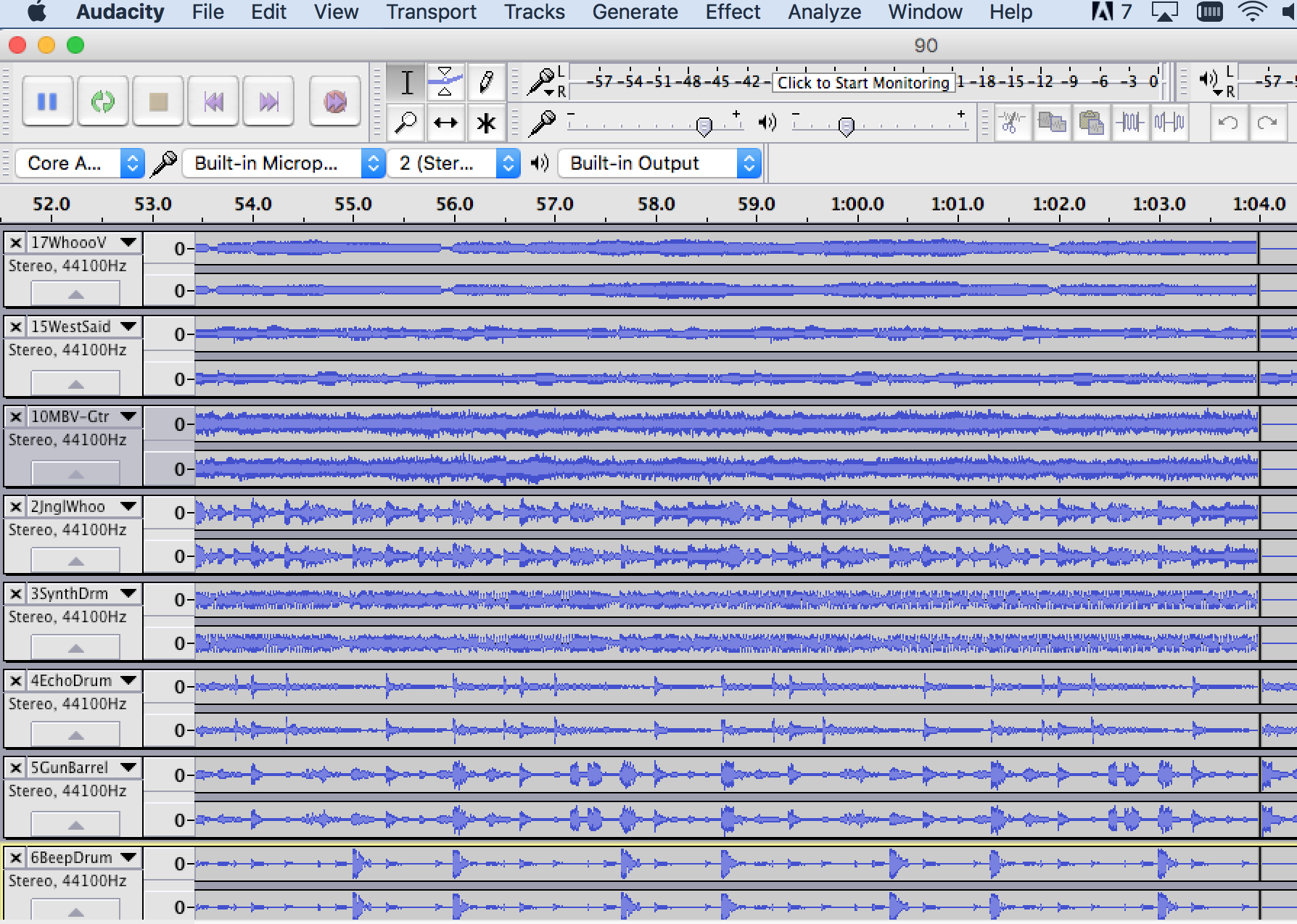

The second song on Assemblage Theory is “Daft Valentine”, so-named because it features guitars reminiscent of Kevin Shields of My Bloody Valentine, and vocals similar to Daft Punk. To build this song, I found 17 separate, unrelated tracks that were 90bpm in the key of G. I saved them together in a folder and then imported the lot into Audacity, a cross-platform, free-to-use audio software tool that has a very flat learning curve. I decided to limit the song to a maximum of five minutes, and then looped each track to fill that space via copy-paste. This creates a visual block of sound (audio in Audacity appears as waves on a graph, see Fig. 1). Playing all 17 tracks together yielded cacophony, so I listened to pairs of tracks together to discover what sounded good. Following that, I began to “carve” the block of sound like a sculpture, removing parts of tracks here and there until a song emerged, and in some cases deleting tracks entirely as the song took shape. I’m a pop traditionalist, so most of the songs I made have an intro, verse, chorus, bridge, and outro, yet they still sound interesting because of the disparate sounds used.

Figure 1, audio in Audacity represented as waves on a graph.

I can guarantee that anyone given the same set of 17 tracks to use over the course of a five-minute song will come up with a different narrative than mine. The individual sounds will be recognizable, but mixed together will create something new and interesting. I have made all 17 of the tracks I used in “Daft Valentine” available here (32 MB ZIP file) should you want to try.

Returning to archaeology for a moment, what we see when we make songs out of the same sound-artifacts is that people can perceive things differently, and can create their own stories out of identical ingredients. Song-making becomes a reflexive exercise, just the same as interpreting data found on a site. When we share that data with others on the team, and with the wider network of people who might be ancillary to the project, we can compare notes and work towards an understanding of what the archaeological record is trying to tell us.

I hope you enjoy Assemblage Theory (on Spotify), and I would love to hear your own creations/remixes of "Daft Valentine" should you be intrepid enough to try.

References

Discography

Reinhard, Andrew. 2019. Assemblage Theory (electronic). https://open.spotify.com/album/5kuFeBnBguoqvEgbXEDGIZ?si=-O5aJOmwRvCD2ZHTJWYGGQ

Reinhard, Andrew. 2016. Punk Archaeology (punk/hardcore). http://andrewreinhard.com/punk-archaeology/

DeLanda, Manuel. Assemblage Theory. 1 edition, Edinburgh University Press, 2016. ↩︎