The Melian Dilemma: Remaking Thucydides

Introduction: the Thucydides Paradox

There is a long-standing tradition of reading Thucydides’ work as a source of political lessons and/or an exercise in political education. This is grounded in Thucydides’ own claims for it as a ‘possession for ever’, inviting readers to compare the events he describes with present and future events which will, ‘because of the human thing’, resemble them. The problem is how this idea is realised in practice. Within historiographical traditions, Thucydides’ claim is assumed to extend to history in general, not just his own work, and taken to imply the usefulness of knowledge of the past as an end in itself, or at best as a source of crude analogies for present events. In political theory, on the other hand, Thucydides’ work is often read as a precursor of normative social science, ignoring its many rhetorical and literary complexities; the absence of statements that can be identified as normative political principles and so claimed as Thucydides’ intended lessons is remedied by taking the statements of characters in his account as expressions of Thucydidean political theory. The most famous example is the way that the claims of the Athenians in the Melian Dialogue are taken, without discussion, to be both the opinion of Thucydides and a true account of the world; hence the idea that he should be seen as the founder of ‘Realism’, establishing the theory that the world is anarchic and that ‘the strong do what they want’ (Morley 2018).

The Thucydides paradox is that in both cases the authority of a complex, ambiguous author is invoked to support a simplistic, reductivist version of his alleged ideas. The historians ignore the fact that Thucydides’ devotion to establishing the truth of past events is a means to an end, not the end itself, while the political theorists ignore the obvious fact that, as Thomas Hobbes had observed, Thucydides never offers precepts or explicit lessons (Hobbes 1629: xxii). The former group elevate historical specificity and ignore the general; the latter elevate the general and ignore the details – and neither group pays any attention to the particular and peculiar nature of Thucydides’ chosen forms of representation, but simply assume him to be writing more or less according to their own generic expectations (Greenwood 2006; Morley 2016).

The present project is part of a wider exploration of the potential for developing Thucydides as a resource for enhancing political literacy and understanding; not as a source of a few universalising principles or maxims that are assumed to explain events in simple terms (compare the ‘Thucydides Trap’ idea applied to relations between the US and China), but as an education in the complexity of the world and the unpredictable nature of events – and the extent to which humans are prone to cognitive bias in trying to think about such things. It seeks to explore the Melian Dialogue as a confrontation between two different world views, the powerful and the powerless, neither of which should be trusted, as well as a depiction of a situation in which counterfactual possibilities – the question of whether things could have turned out differently, and the question of what might have had to be different in order for things to turn out differently – are constantly raised or implied.

But it is not enough simply to offer a different interpretation of Thucydides – these are common enough, and the idea that the Melian Dialogue can be read as a critique of Realism is nothing new (Johnson 1994). The problem with contemporary evocations of Thucydides and his political message is not just that they present a version of his ideas that is simplistic and arguable at best. Equally problematic is the elitist dimension to this appeal to authority; the undeniable difficulty of Thucydides’ work is taken not as an incentive to explain and explore but as a means of establishing the writer’s own superior education and understanding, with the implication that true understanding can be gained only through lengthy engagement with the entire text and the tradition of scholarship. It is certainly the case that one problem with Realist readings of the Melian Dialogue is their failure to consider what happened to the Athenians afterwards – but does that mean that any reading of sections of Thucydides’ work, rather than the whole thing, is unavoidably flawed?

The challenge for any attempt at setting up Thucydides as a resource for political education is that his work is long, sometimes tedious, and often inaccessible; how can it be made usable, without stripping out the ambiguity and complexity that is (I would argue) the point of the exercise? One of the basic principles of this project is that Hobbes had the answer:

Digressions for instruction’s cause, and other such open conveyances of precepts, he never useth: as having so clearly set before men’s eyes the ways and events of good and evil counsels, that the narration itself doth secretly instruct the reader and more effectually than can possibly be done by precept. (1629: xxii)

‘The narration itself doth secretly instruct the reader’ – anticipating by nearly 350 years Hayden White’s insights into ‘the content of the form’ and the fictions of factual representation (1987); still more is this the case in those passages in Thucydides where he breaks from narrative to explore other means of communication. In the notoriously problematic speeches, we are not presented with the historian’s own account of the speaker’s character and ideas; rather, we are (or feel ourselves) addressed by the speaker, seeking to persuade us and perhaps at the same time inadvertently revealing something of themselves, and we are (or feel ourselves) placed in the same position as that speaker’s original audience, struggling to evaluate their words and decide on the right strategy (cf. Foster 2010). In the Melian Dialogue, we are presented with a tragic agon, bringing the arguments to life and pulling our sympathies backwards and forwards, with the painful knowledge of where this is actually going to end (Hardwick 2015).

Thucydides’ freedom from generic conventions and willingness to experiment with rhetoric and form in order to help his readers understand the world surely gives us licence to experiment ourselves. Tragedy is not the only thing that the Melian Dialogue brings to mind; as exponents of game theory like John van Neumann, Thomas Schelling and Yanis Varoufakis have recognised, it also resembles the world of the Prisoner’s Dilemma and other games (Morley 2015; Dal Borgo 2016). Turning it into a playable game also, potentially, overcomes the common obstacle to academic work having any ‘impact’; namely, if there is not already a natural audience or existing demand for what you have to offer, why should anyone be interested in having their assumptions unsettled? The aim is therefore to create a game that is sufficiently interesting and/or pleasurable to play in its own right, that can then help to lead the player towards a deeper understanding of the broader political issues.

Game Framework

The Melian Dialogue can in fact be imagined as several quite different sorts of games. One approach, that followed by game theorists, is to focus on the situation itself, and I have developed two card-based games focused on contests in which different sorts of imbalance are built in. Both games are interesting enough to play on a single occasion, as a basis for structured discussion afterwards, but only one of them would conceivably merit repeat plays for pleasure.

The main game focuses more on the text of the Dialogue and the decisions made by its protagonists; it turns it into a piece of interactive fiction, reminiscent of the ‘choose your own adventure’ genre, in which the player takes the role of either the Athenian commander or one of the leaders of the Melians, and works their way through a series of choices and their consequences. They encounter at least some of the words spoken by their opponents in the original, and face at least some of the same dilemmas – but also others, if their decisions lead them in directions which are only implied counterfactuals in Thucydides’ account. The range of possible outcomes is of course larger than the single historical result.

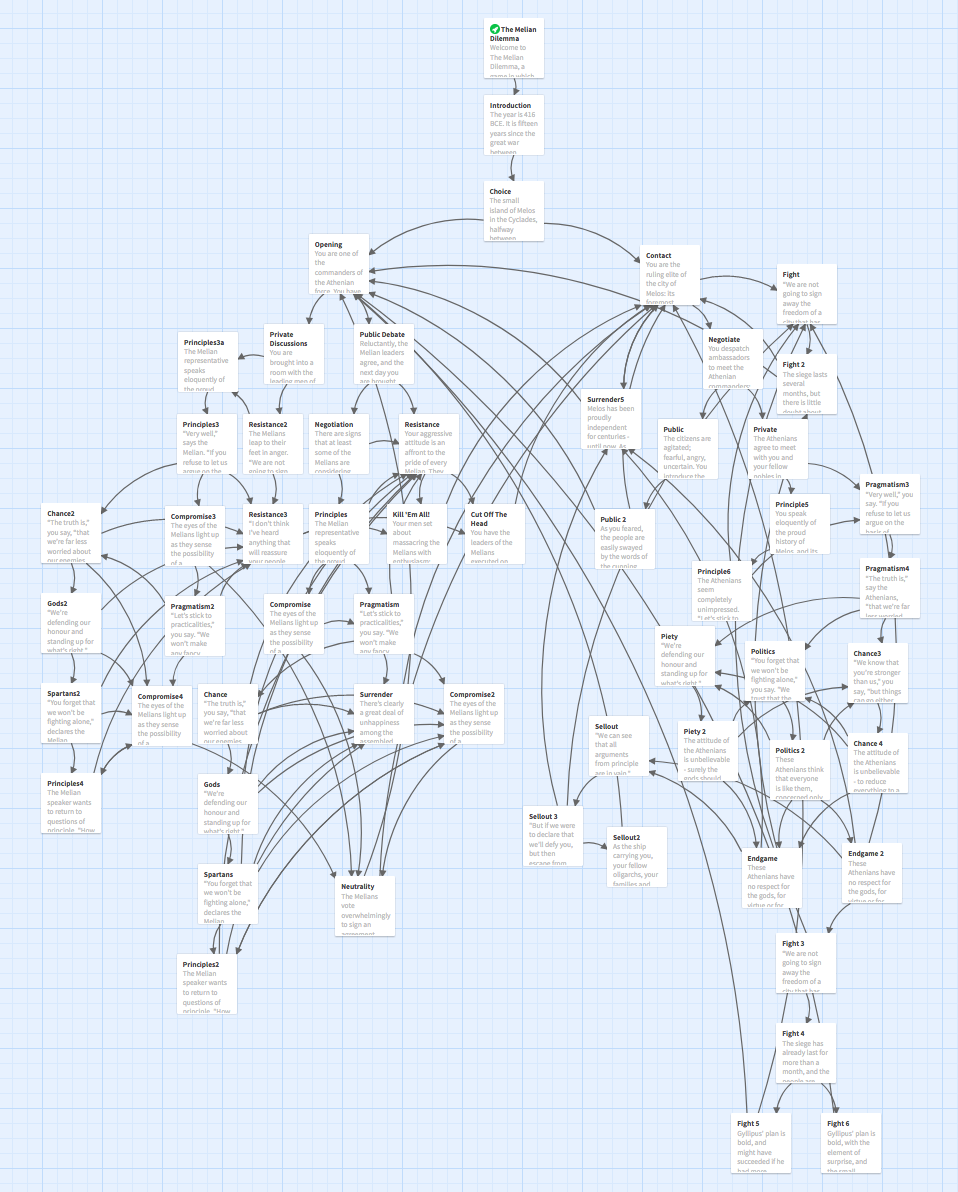

The obvious, if not inevitable, tool for constructing the game was Twine (version 2.2.1, using the default Harlowe format), which is designed specifically for the creation of branching narratives in which the player reads some text and then chooses between a limited number of options by clicking on hyperlinks which take them to new passages of text. Twine and its potential have been discussed and demonstrated in previous Epoiesen pieces by Juniper Coyne (2017)and Jeremiah McCall (2018), and I have little to add to their comments except to stress how easy it is to use. For the most part, the Melian Dilemma is extremely simple, relying almost entirely on simple hyperlinks between passages (the story map, with some narrative choices looping back on themselves, is rather more complicated, see figure 1).

Figure 1, Representing the Story Map within Twinery

There are just two respects in which I have taken advantage of the macros that can be added to Twine stories. The first is to introduce an element of randomness into the results of choices, using the (*either:*) macro, so that a player clicking on certain hyperlinks may end up in one of two different narrative arcs – reflecting the obvious truth that events are never wholly determined by the decision of one party, but that the opposition are also making critical decisions. The second uses the (set:) macro to create a variable that increases by 1 every time the player has another go at the Melian role; after a certain number of tries, the (if:), (else-if:) and (else:) macros allow the unlocking of new possibilities.

Design and Gameplay Issues

The development of the game involved two separate processes. The first was the modelling of the Melian Dialogue itself. I edited and adapted the text, having made the decision early on to use a compressed version which seeks to distil the essence of the most important exchanges and arguments, rather than asking players to work through the entire negotiation as originally written, and divided it into manageable sections (not least to avoid where possible players having to scroll down). In parallel, I constructed the underlying decision tree, to identify points where one might surmise a choice was made by one or other party, whether to adopt one line of argument or another or to respond to the claims of the other side – or, eventually, to break off discussion.

The second process was more complex and speculative: identifying the whole range of outcomes which would be possible if a player chose not to follow the same route as the historical actors. One starting assumption was that there is no specified goal, whether you are playing Athenians or Melians, and certainly historical accuracy is not required or prioritised (though of course one can always play the game historically, in which case you do tend to end up with the expected result, but perhaps with more insight into the factors which shaped the decisions of both sides). Rather, it is open to the Athenians to seek to avoid conflict if at all possible, or to the Melians to surrender rather than sacrifice the city in the name of sovereignty. Of course, the response that players can expect from the other side is historical – if you are playing the Melians, the Athenians will not suddenly relent and sail away.

As the more powerful side, the Athenians have much more freedom of action. If the player defines ‘winning’ solely in terms of the conquest of Melos, they will always win; the question is whether they feel comfortable with the values and assumptions they thus re-enact (or with the implication that it is this winning mentality that leads Athens into disaster in the future). Only if the player aims at finding a less bloody resolution do other factors come into play, including the use of Twine’s (either:) macro to create the possibility that e.g. the Melians might sometimes be persuaded to be more reasonable but will never wholly lose an inclination to defend their sovereignty.

The Melians’ basic choice is between surrender and death – arguably, they get to decide between different ways to lose (and different paths to that end). But there are three main additional possibilities. Two of these pick up on a point in Thucydides’ account that is sometimes overlooked: it is not the Melian people but their leaders who negotiate with the Athenians and decide that sovereignty is more important than safety, and this might imply that the fates of the people and their leaders might be different, rather than everyone perishing together. The third possibility is firmly excluded by Thucydides, and it is interesting to note that a limited Twitter poll suggested that most (60%) of respondents agreed with him, but a plausible historical argument can be constructed for allowing at least a small chance in the game that the Spartans will turn up to rescue Melos (cf. Morley 2019). This latter possibility is unlocked only after playing the Melian role several times; the point is not to create a challenging route to victory that a player might stumble across through luck the first time they play, but rather to emphasise the unlikeliness of such an outcome and raise the question of whether it is rational to gamble the fate of the whole city on that chance.

Using the Game

It should already be clear how far the game design is consciously didactic; it aims not to teach a specific lesson, but to highlight the issues and assumptions involved in choosing a goal and selecting between options, for either side, and the way that the situation sets limits on what either side can do. For the moment, those playing the game online are free to ignore such issues altogether, however much the text tries to prompt them, and to treat it simply as an intellectual exercise. In due course I plan to incorporate the game into a website which will make the issues more explicit, and potentially gather data about people’s responses (if only on the frequency with which people arrive at different outcomes).

Primarily, however, the game is intended to be used in the classroom or as part of a workshop; students (in the broadest sense) can either play the full version solo or in pairs and then join in a discussion afterwards, or the whole group can be led through a simplified version of the game (still in preparation) by a facilitator, so that the issues involved in each decision are discussed before each choice is made. In either case, students can then be asked to reflect on individual passages from the Melian Dialogue, to weigh up their arguments and assumptions and consider possible analogies with the present day; and the whole thing can be set in a wider context by viewing a video adaptation (see Might and Right) or short video lecture Thinking Through Thucydides. My colleague Lynette Mitchell and I are collaborating with The Politics Project, an NGO dedicated to enhancing political literacy in schools through workshops and digital surgeries (workshops), to create a set of three one-hour workshops built around this game as well as the two card-based ones – but the game can certainly be adopted as a resource by other schools and other non-profit organisations (we would simply like to be given credit, and receive reports of how it goes).

Again, it would be interesting to collect data on how players approach the game: on the first occasion this exercise was tried out with a non-academic group (from the University of the 3rd Age in Dartmouth, Devon), the ‘Melians’ started out relatively calm and reasonable, and became progressively more belligerent as the dialogue continued, as they felt trapped by Athenian intransigence. This does suggest wider potential for the game as an exercise in understanding negotiation and conflict, for example for civil servants and business people…

Play The Melian Dilemma, hosted on Philome.la.

An archived copy, as of February 6th 2019, can also be played via Github.

Works Cited

Coyne, Juniper. 2017. “Destory History”. Epoiesen DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22215/epoiesen/2017.4 link

Dal Borgo, Manuela. 2016. “Thucydides: Father of Game Theory”, PhD, University College London. Link

Foster, Edith. 2010. Thucydides, Pericles, and Periclean Imperialism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Greenwood, Emily. 2006. Thucydides and the Shaping of History, London: Duckworth

Hardwick. Lorna. 2015. “Thucydidean Concepts”, in C. Lee & N. Morley (eds.) A Handbook to the Reception of Thucydides, Malden MA: Wiley Blackwell, 493-511

Hobbes, Thomas. 1629. ‘To the Readers’, in Eight Books of the Peloponnesian Warre Written by Thucydides the Son of Olorus: Interpreted with Faith and Diligence Immediately out of the Greek by Thomas Hobbes, London: Henry Seile

Johnson, Laurie M. 1994. “The Use and Abuse of Thucydides in International Relations”, International Organization 48.1: 131-53. DOI: 10.1017/S0020818300000849

McCall, Jeremiah. 2018. “Path of Honors: Towards a Model for Interactive History Texts with Twine”. Epoiesen. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22215/epoiesen/2017.16 link

Morley, Neville. 2015. “The Melian Dilemma: Varoufakis, Thucydides and Game Theory”, The Sphinx Blog 27/3/2015 link

Morley, Neville. 2016. “Contextualism and Universality in Thucydidean Thought”, in C. Thauer & C. Wendt (eds.) Thucydides and Political Order: Concepts of Order and the History of the Peloponnesian War, Basingstoke & New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 23-40

Morley, Neville. 2018. “Thucydides: the Origins of Political Realism?”, in M. Hollingsworth & R. Schuett (eds.) The Edinburgh Companion to Political Realism, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 111-123

Morley, Neville. 2019. “They Win Again?”, The Sphinx Blog 24/1/2019 link

White, Hayden. 1987. The Content of the Form: Narrative Discourse and Historical Representation, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Cover image and masthead courtesy Neville Morley.

'The Melian Dilemma: Remaking Thucydides' is shared under CC BY-SA.

'The Melian Dilemma: Remaking Thucydides' is shared under CC BY-SA. The 'Melian Dilemma' game is shared under CC BY-NC-SA.

The 'Melian Dilemma' game is shared under CC BY-NC-SA.