Visualizing the York Minster as Papercraft

The use of paper as a mechanism for visualization is an ancient art form, making it a fitting medium for the display of heritage monuments and historic materials. Papercraft is an artform that employs paper or card as the primary medium for the construction of three-dimensional objects. It is a method of visualization that requires the creator to analyze and study a resource in great depth, and with technology of the 21st century it is possible to plan, build, and even imagine these models within the space of virtual reality. This paper outlines the process for creating a papercraft model of the York Minster beginning with the digitisation of the structure in Adobe Illustrator and ending with its reconstruction in paper format. Additionally, the potential for future enhancement of the model through digital means will be discussed.

Heritage papercraft models that are generally distributed to the public for download involve downloading relatively simplified templates that are then cut and glued together (see Ellwood 2018; SEAArch 2007). The process for visualizing a heritage resource as papercraft requires a significant amount of close analysis and artistic interpretation. Even the simplest of papercraft models require that the creator view the subject in great detail in order to note the distinct shapes, curves, and details of the resource. Those details then have to be adapted to paper format and made possible for reconstruction. Subsequently, any individual who takes on the challenge of creating a second-hand papercraft adopts this educational component as they fit the pieces together.

The approach for this project was to give an opportunity for varying levels of difficulty to be incorporated into the building of the model, while also leaving the color scheme as a blank canvas for the possibility of incorporating projection technologies in the future. This blank canvas also allows for a coloring element to be applied by other users. The York Minster was chosen as the topic for reconstruction because it exhibits extreme detail in its negative spaces including windows, doorways, and roof extremities, while also representing a central location to the city of York that is easily recognisable. The Minster is a heritage monument that was first constructed around 627 AD, and reconstructed in its present Gothic-style between 1220 and 1472 (History of York, n.d.).

The vision for the end product of this papercraft model was to be able to showcase the windows using a central light source within the model. Therefore, it was decided that the best approach to achieve this visualization would be to focus efforts of design and detail on the larger windows.

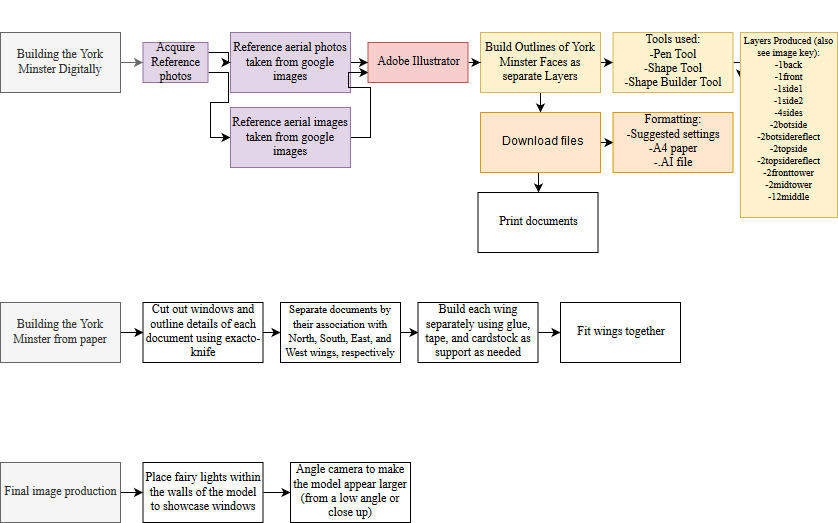

Figure 1. Model Workflow.

Methodology

The methodology for the production of this project involved three stages:

a) data acquisition and modelling in Adobe Illustrator,

b) printing, cutting and building, and

c) final image production.

This process can be seen in the model workflow above (Figure 1). ‘Data’ in this instance refers to the reference photos used to create the model within Adobe Illustrator. These photos were personally taken for each face of the Minster from the ground and from the tower. Additionally, aerial photos were sourced through google imagery to supplement for any areas that were not visible in the collected imagery.

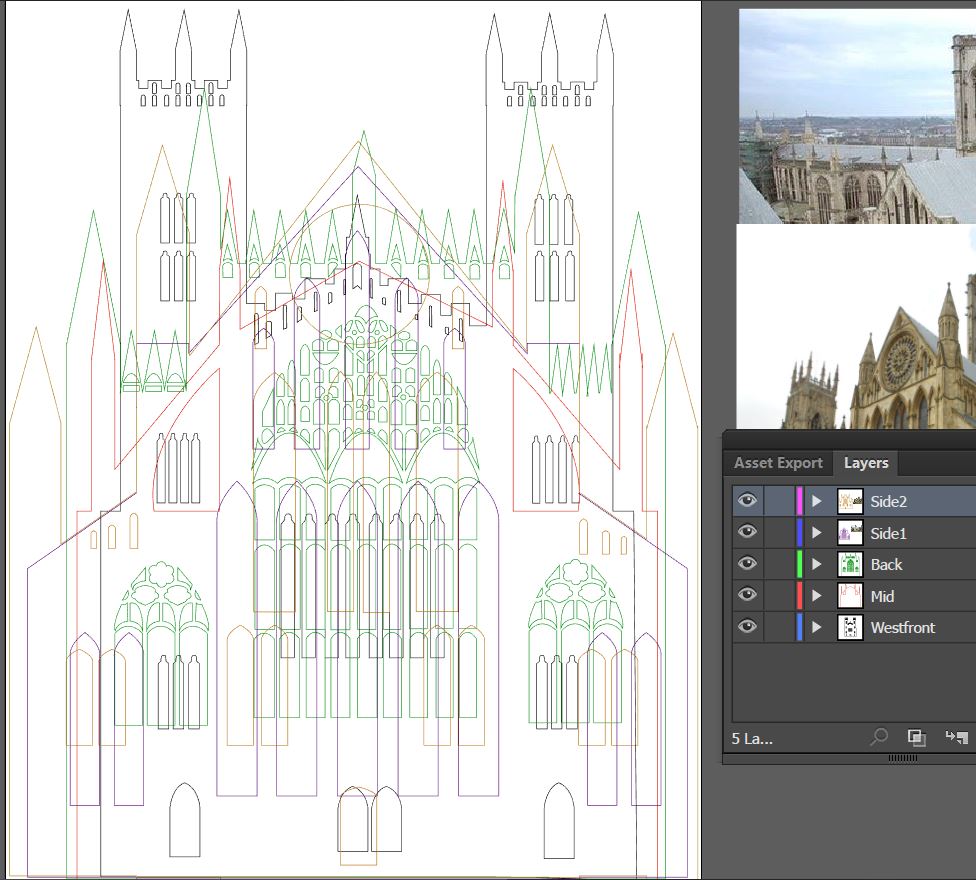

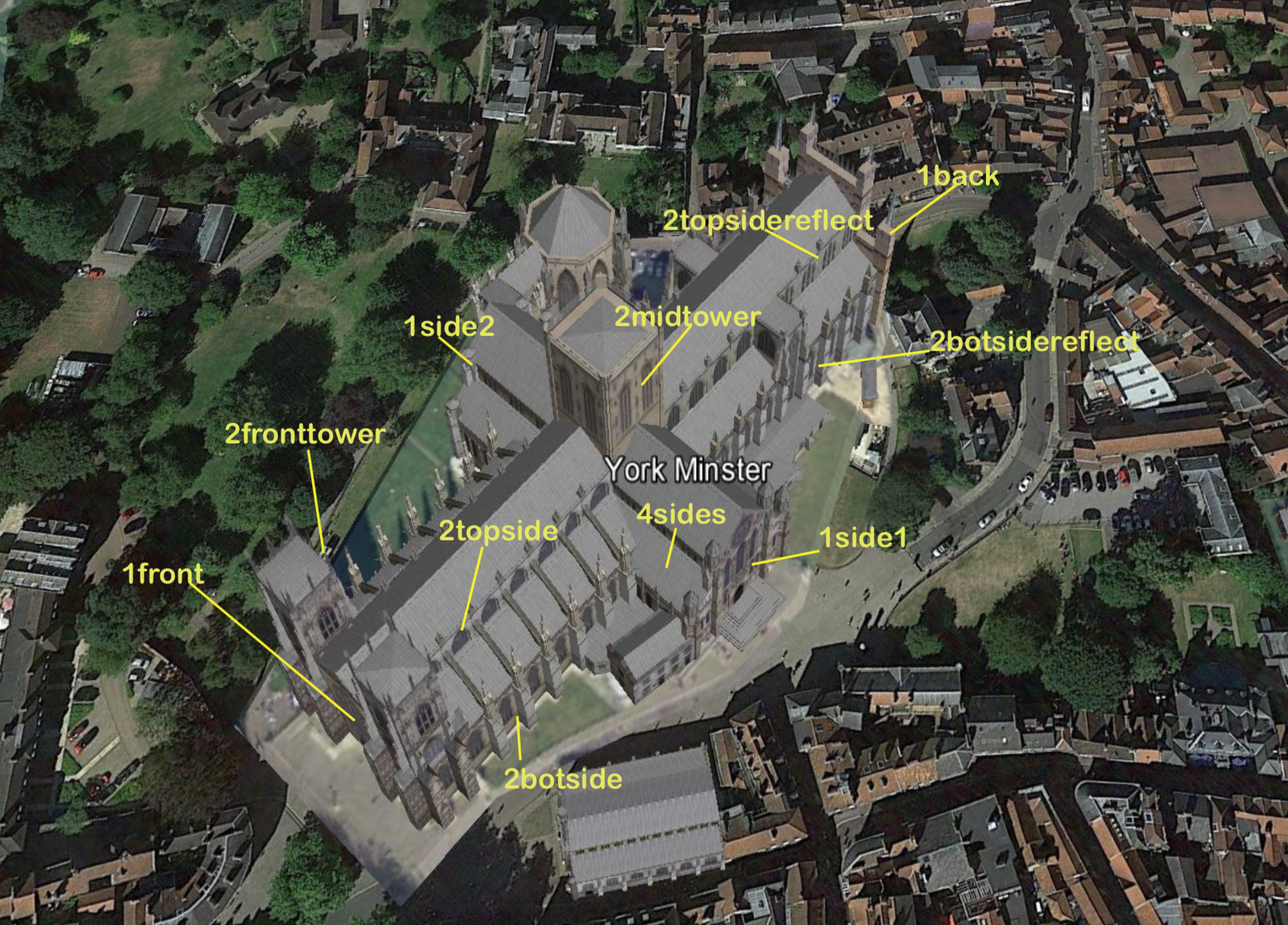

Adobe Illustrator was chosen to make the templates for the paper cutouts because of the programs ability to construct and merge together basic shapes on top of a pre-established A4 page layout. The tools used within Adobe Illustrator were the pen tool, shape builder tool, and rectangle/ellipse tool. Each face of the Minster was constructed on a separate layer with its own distinct color, and each layer was toggled on and off to ensure consistency in scale (Figure 3). Scale was first established through the modelling of the West-facing entrance of the York Minster. Because the roofing detail on the face of the entrance has the tallest point of the structure, it was used to fill the vertical extent of the page. Altogether, twelve separate layers were constructed for the model. These are listed in the workflow under “Layers Produced,” and the faces that they represent are visualized in the Figure 2 Image Key.

Figure 2. Image Key for Flow Chart. Base Image Courtesy Google Earth.

Figure 3. Progress screenshot showing the distinguished layers during the construction of the model in Adobe Illustrator.

For planning purposes and any potential future distribution of the project, the layer files were labelled based on the number of copies required for printing. For example, "2fronttower.ai" would require two copies and "4sides.ai" would require four copies. The layers are made publicly available from a downloadable google documents folder which can be accessed here: https://epoiesen.github.io/artefacts/yorkminster-papercraft/.

Templates were purposefully saved as .AI files, rather than .pdf, so that editing could be enabled if necessary.

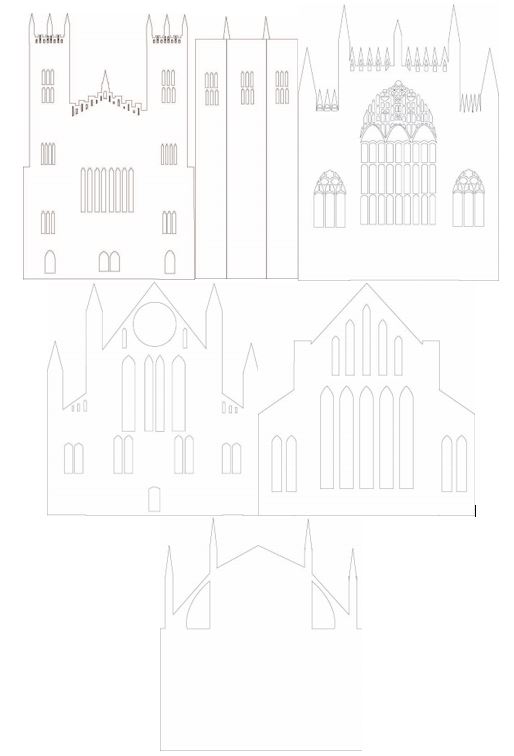

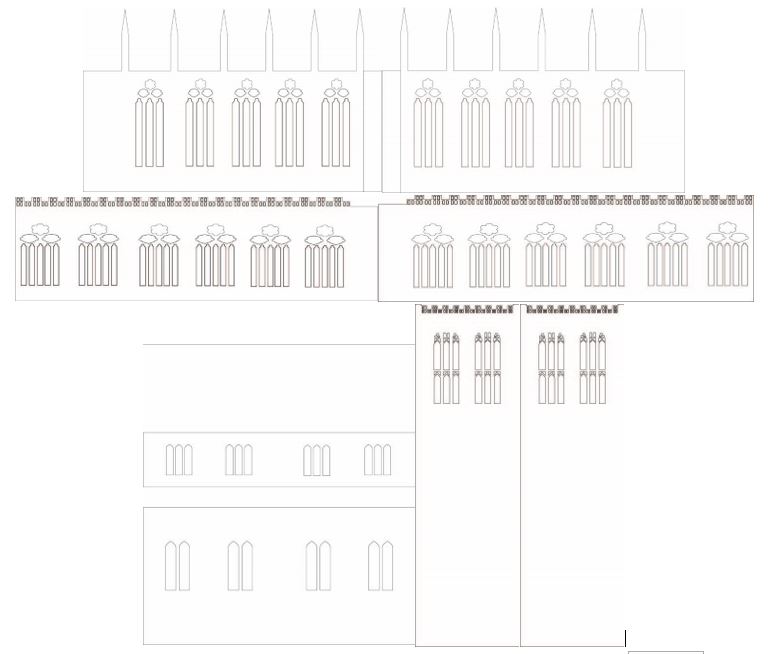

Once the layers were completed, they were printed onto A4 printer paper and then prepared for cutting. The template outlines can be viewed in figures 4 and 5. The tools used during the cutting and building process were a cutting board and an exacto-knife. This process of cutting the entire model took about 8 hours to complete in one sitting and in order to save time some of the curved details were reduced to straight cuts.

The building of the model required consistent reference to photos of the Minster, in addition to card stock supports for the thin A4 paper. To combat time constraints, it was decided that the most detailed pieces would be the focus of the build. These included the Eastern (back) window, the east wing, the middle tower, and side 1. Full pages of card stock paper were used as central support for the frame of the model, and small strips of card stock were used as corner supports to connect pages together. Once the east wing, tower, and side 1 were completed and pieced together, it was decided that this stage of building point would be an acceptable stopping point for proper visualization to occur.

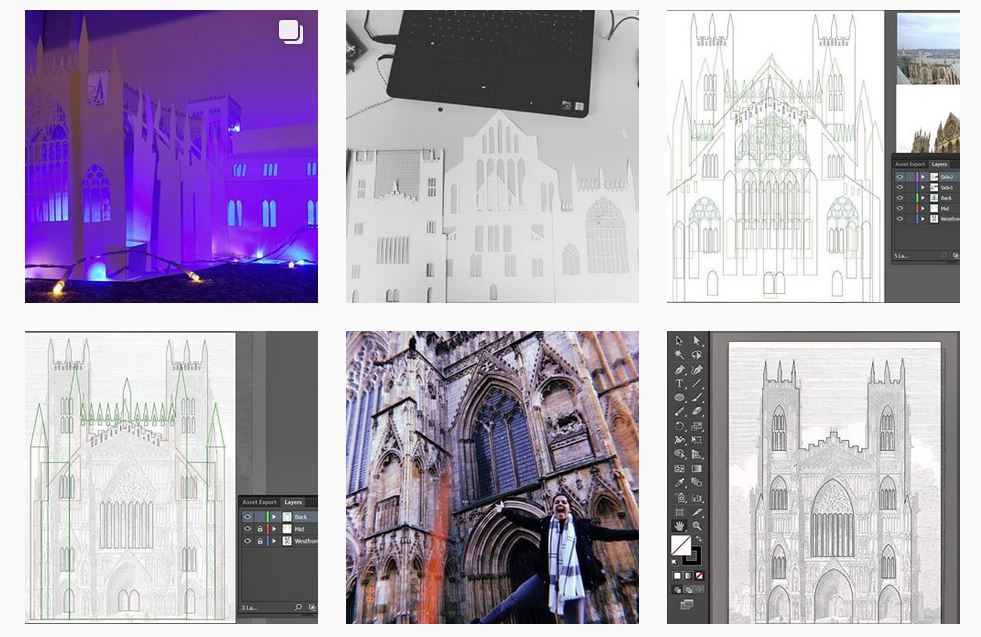

In order to achieve the desired lighting for presentation of the model, two small strings of blue and white lights were purchased to be placed within and along the exterior of the model. The blue lights were woven within the windows and the central tower of the model, while the white lights were laid on the outside of the model. To achieve a clean white background for photography, the model was placed on the floor under the desk, and the only light source used in the photo was that of the model lights. This set up process can be viewed in figure 6.

The final display images of the model are shown in figure 7 below. These angles were chosen as they highlight the detail of the back window, capture the central tower, and create the effect of a scale larger than reality.

Figure 4. Left to right: 1front, 2fronttower, 1back, 1side1, 1side2, 12middle.

Figure 5. Left to right: 2botside, 2botsidereflect, 2topside, 2topsidereflect, 4sides, 2midtowe.

Figure 6. Setting up the model for photographing.

Figure 7. Final visualization of the York Minster Papercraft Mode.

Changes to be Made

With the issues of time constraint and budget, the quality of the model lacked in certain areas. A4 printer paper is quite thin and therefore difficult to work with when creating a standing model. If budget allows, it would be preferred to print the model layers on a thicker card stock paper. This way, the additional support and gluing would not be necessary, and a significant amount of time would be saved in the construction of the model. Another issue with the design of the templates is the thickness of the lines and the time it takes to carefully cut each individual window. During this process, decisions were made to create sharp cuts on the windows rather than following the exact outline in order to save time. If the lines were drawn at a thinner width, these decisions would be made less obvious when looking at the built model.

Public Outreach

Social media has become an important addition to public outreach and education in the field of archaeology, and many individuals within the community are devoting significant effort towards reaching online communities to foster engagement with a worldwide audience (Watrall 2002, 169; Richardson 2013, 4). With the impact of new methods of data sharing and collaboration, archaeology is able to be experienced, shared, and archived in new and accessible ways (Jeffrey 2012, 553). Within all of these social networks, blogs, and multimedia pages are communities of archaeologists that can be reached through targeted titles and tags.

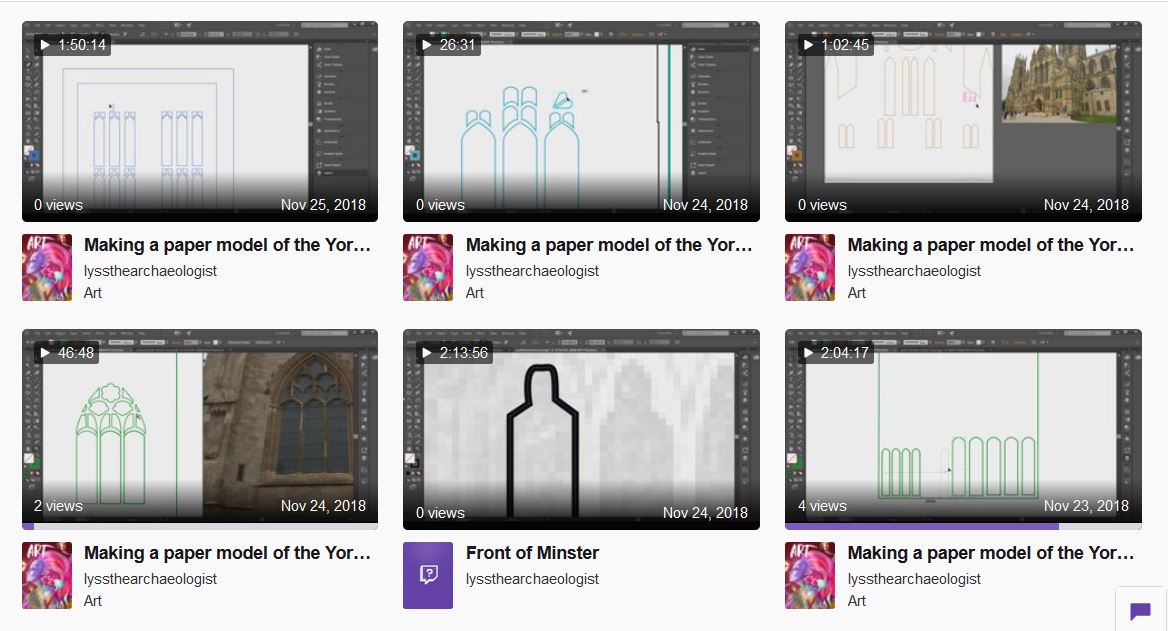

Throughout the duration of the project, various methods of public outreach were incorporated. These included a live twitch.tv streaming of the adobe illustrator and building processes, as well as photo and video updates on archaeology blogs created on Instagram and Tumblr (figures 8 and 9). Live streaming the building process allows for the audience to interact with the creator, ask questions about the process, and to be inspired and learn from the methods of building being presented. Similarly, the process of blogging provides viewers with updates on projects presented in a casual and relatable format that is easy to understand and engage with (Rocks-Macqueen et al. 2014, 6). This method of sharing allows for content to be freely accessed and engaged with.

The York Minster Paper Craft Model was created with the intention of reaching three specific audiences on social media platforms: Archaeologists/digital archaeologists, Papercraft enthusiasts, and the community of York. These communities were targeted through specific hashtags—such as #DigitalArchaeology, #York, #Papercraft—on all platforms, including links to the twitch.tv stream with each post.

Figure 8. Screenshot of twitch.tv live stream video.

Figure 9. Screenshot of project progress updates on Instagram.

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

The papercraft process does not have to stop after the building is complete. There has been previous research conducted, such as that of Stu Eve, in augmenting papercraft models with 3D and virtual reality overlay. Eve’s research of “Augmenting a Roman Fort” incorporated a virtual experience of various Romanesque scenes that one could view when pointing a smartphone or tablet at the papercraft model of a Roman Fort. By clicking on various buildings within the interface, one could learn about the history and use each individual structure. Stu comments on this experience by stating “For me that is one of the beautiful things about AR, you still have the real world, you still have the real fort that you have made and can play with it whether or not you have an iPad or Android tablet or what-have-you” (Eve 2011). This process of creating augmented reality for heritage visualization could also be applied to the York Minster papercraft model. Possible projected scenes included in this project might reference various activities that went on around and inside the structure, or even an interpretative animation of the building process that occurred in 637 AD (History of York, n.d.).

When building a cultural heritage item for an audience, interactivity is one of the most important factors if the objective is to gain interest and inspire. It is easy to glance over 3D models on a computer screen, but when one is involved in the manifestation of a product and see it come together with their own eyes, a sense of ownership and meaning is incorporated into the object being created. This was my experience throughout the process of constructing the York Minster model. The time, effort, and interaction with audiences during the various phases of construction enhanced my appreciation not only for the art form of papercraft, but also for the history of the Minster and the understanding of the stylistic choices made during its construction so many years ago. The field of archaeology is becoming cluttered with 3D models of artifacts and monuments because of how easy it is to produce them. While these models play an important role in keeping a digital record of the past, they fail to engage with audiences and more importantly they fail to credit the thought processes and efforts that went into constructing the original objects. These past ‘efforts’ are what give an object meaning, and without a visual representation of that effort, it becomes just another image on the screen.

The value of this resource comes from its accessibility and owes its potential for success to current media tools that allow for archaeologists and heritage enthusiasts to share their experiences on the internet. The ability to observe the model building process, interact with the builder, and then download the files to create your own model makes it easy for anyone who is interested in the art form to be a creator and participate in the history of the object. The history of the York Minster and other heritage sites do not have to remain in the past, and instead their narratives are continually being built upon and shared through archaeology and visualization.

References

Ellwood, N. (2018). King’s Manor – The University of York, Department of Archaeology. [online] Nickellwood.co.uk. Available at: http://www.nickellwood.co.uk/projects/kings-manor-york-papercraft/ [Accessed 29 Nov. 2018].

Eve, S. (2011). Augmenting a Roman Fort. [online] Dead Men's Eyes: Augmented Reality and Heritage. Available at: http://www.dead-mens-eyes.org/tag/roman/ [Accessed 29 Nov. 2018].

History of York. (n.d.). York Minster. [online] Available at: http://www.historyofyork.org.uk/themes/york-minster [Accessed 29 Nov. 2018].

Jeffrey, S., 2012. A new digital dark age? Collaborative web tools, social media and long-term preservation. World Archaeology, 44(4), pp.553-570.

Richardson, L., 2013. A Digital Public Archaeology?. Papers from the Institute of Archaeology, 23(1), p.Art. 10. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/pia.431

Rocks-Macqueen, D. and Webster, C. (eds) Blogging Archaeology. E-book: Landward Research. 20-35. Available at http://www.digtech-llc.com/s/2014-Blogging-Archaeology-eBook-35vc.pdf

Watrall, E., 2002. Digital pharaoh: Archaeology, public education and interactive entertainment. Public Archaeology, 2(3), pp.163-169.

Cover Image York Minster, courtesy Alyssa Loyless

Masthead Image "Bulley, Eleanor. 'Great Britain for Little Britons. A book for children' p45."British Library Flickr