Messy Assemblages, Residuality and Recursion within a Phygital Nexus

Abstract

This visual essay is a reflection on the movement of objects and images within the phygital and, in particular, how different components of assemblages meet, mingle and sometimes experience ontological shifts, when an artist and an archaeologist, and their practices and apparatus, intra-act within a ‘phygital nexus’. Phygital objects are digitally defined but can be invoked, instantiated and brought into constellation with other entities both physically and virtually. A phygital nexus can be thought of as a no-place and an every-place where digital and physical worlds intersect; a space where novel, ‘messy assemblages’ can emerge. In our collaboration, we constantly subvert the phygital nexus to appropriate and remix components of multifaceted, multi-(im)material, and multi-temporal phygital objects that recall themselves - nested and extended assemblages of persistent (im)material artefacts and other residues - and refract them through both our distinct, and combined interdisciplinary, critical practices, to produce new ontological assemblages, further residues of an ongoing collaboration, which we map onto Gavin Lucas’ Grid of forces of assembly and disassembly.

This visual essay is a reflection on the movement of objects and images within the phygital and, in particular, how different components of assemblages meet, mingle and sometimes experience ontological shifts, when an artist and an archaeologist, and their practices and apparatus, intra-act within a ‘phygital nexus’. Phygital objects are digitally defined but can be invoked, instantiated and brought into constellation with other entities both physically and virtually. A phygital nexus can be thought of as a no-place and an every-place where digital and physical worlds intersect; a space where novel, ‘messy assemblages’ can emerge. In our collaboration, we constantly subvert the phygital nexus to appropriate and remix components of multifaceted, multi-(im)material, and multi-temporal phygital objects that recall themselves - nested and extended assemblages of persistent (im)material artefacts and other residues - and refract them through both our distinct, and combined interdisciplinary, critical practices, to produce new ontological assemblages, further residues of an ongoing collaboration, which we map onto Gavin Lucas’ Grid of forces of assembly and disassembly.

The residues and traces of this reflexive collaboration includes this essay and an assemblage of art/archaeology forms that comment, recursively, on both previous and subsequent assemblages, and our practices.

Visual Abstract

Introduction

This visual essay is a reflection on the movement of objects and images within the phygital and, in particular, how different components of assemblages meet, mingle and sometimes experience ontological shifts, when an artist and an archaeologist, and their contrasting practices and apparatus intra-act (sensu Barad 2007) within a phygital nexus (e.g., Gant and Reilly 2017). A phygital nexus can be thought of as a no-place and an everyplace in which the boundaries between what is physical and what is virtual are blurred, where digitally-defined objects (actants) are susceptible to transmutations and may be (re)deposited within multiple parallel or intersecting physical and digital assemblages (e.g. Reinhard 2019a), and are able to ‘jump’ almost anywhere in our digitally hyper-connected universe. In addition, phygital objects can be invoked, instantiated and brought into constellation with other practices (1) and entities both physical and virtual, and ‘messy’ assemblages can, and do, emerge from these interventions. Phygital transformations, moreover, may be multi-directional: digital objects can become physical and, conversely, material instantiations can be virtualised.

In our collaboration, we constantly subvert the phygital nexus to enable us to appropriate and remix components of multifaceted, multi-(im)material, and multi-temporal phygital artefacts that recall themselves - nested and extended assemblages of persistent (im)material artefacts (2) and other residues - and refract them through both our distinct, and combined interdisciplinary, critical practices, to produce new ontological assemblages, further residues of an ongoing collaboration. The residues and traces of this reflexive, team SHaG-like collaboration, has evolved iteratively as we each handed over work in progress to the other (Figure 1) to be enriched and developed (see Sillman, Humphrey and Green n.d.), and includes this essay and an assemblage of art/archaeology pieces that comment, recursively, on both previous and subsequent assemblages, and our practices.

Figure 1: Interlaced studios

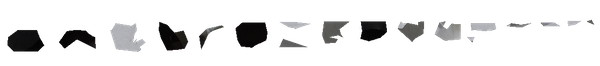

Figure 2: phygital Old Minster UV fragments collage

Assemblages and Residuality

The term ‘assemblage’ has many connotations. In art it refers to the combination of found and collected objects into a composition (e.g. Figure 2). In western tradition, it is commonly asserted to have begun with Picasso in 1918 and extends like collage as a methodology (e.g. Craig 2008) to take images and objects away from their proper function so as to see them for what they might be (Hamilakis and Jones 2017, 77-79). As Theodor Adorno would say “Art is magic delivered from the lie of being truth”. In archaeology, the concept of assemblage has traditionally had two main distinct, but overlapping, meanings. It can refer to “a collection of objects associated on the basis of their depositional or spatial find-context (e.g. midden assemblage) and a collection of one type of object found within a site or area (e.g. pottery assemblage)” (Lucas 2012, 193-4). However, Gavin Lucas, building on Manuel DeLanda’s assemblage theory, who draws, residually, on the philosophy of Giles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, has rearticulated the concept of archaeological assemblages to foreground their external relationships, such as their relations to their environment and other assemblages, as opposed to the internal configurations of their component parts, which are recognized as having a certain amount of autonomy, insofar as they can move between assemblages and recombine elsewhere in other spatiotemporal contexts.

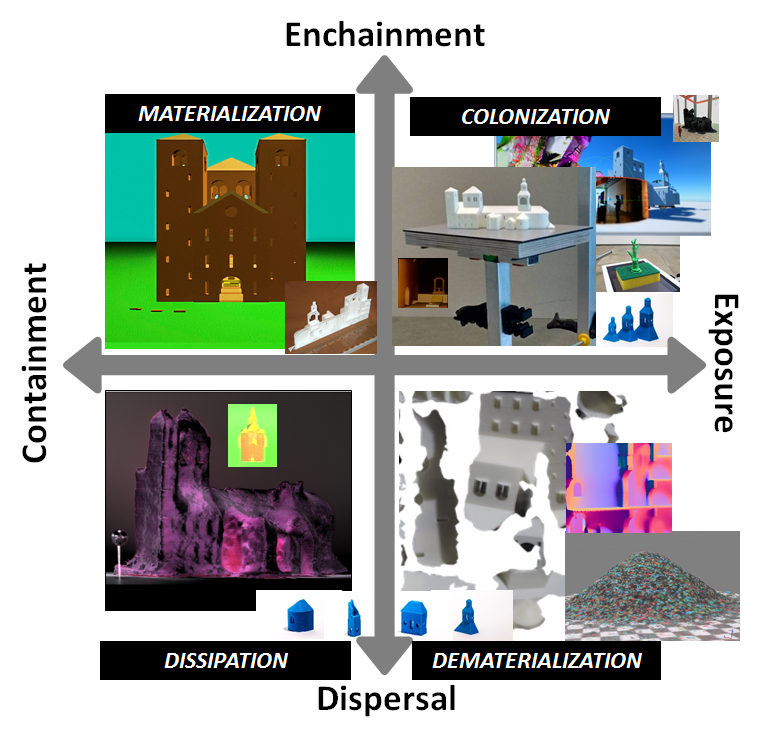

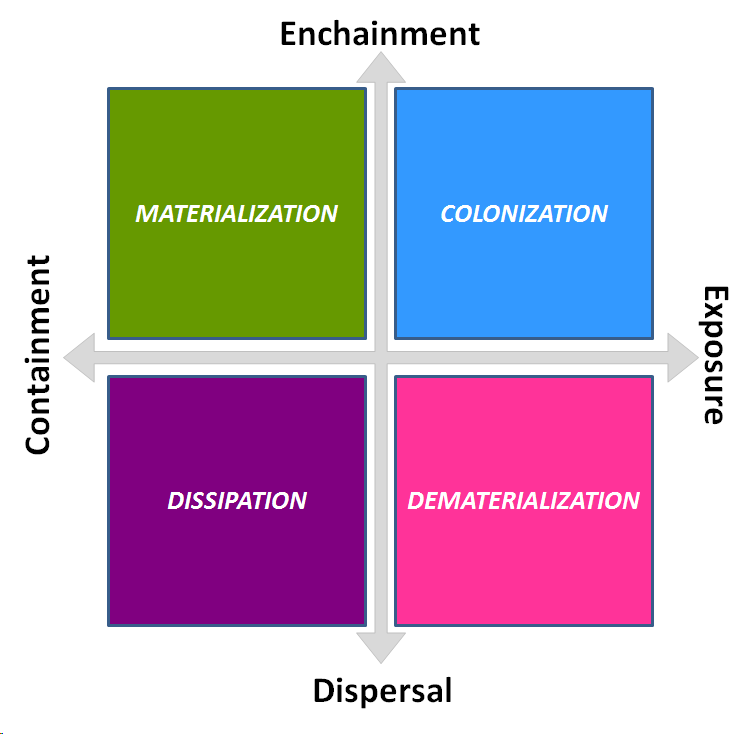

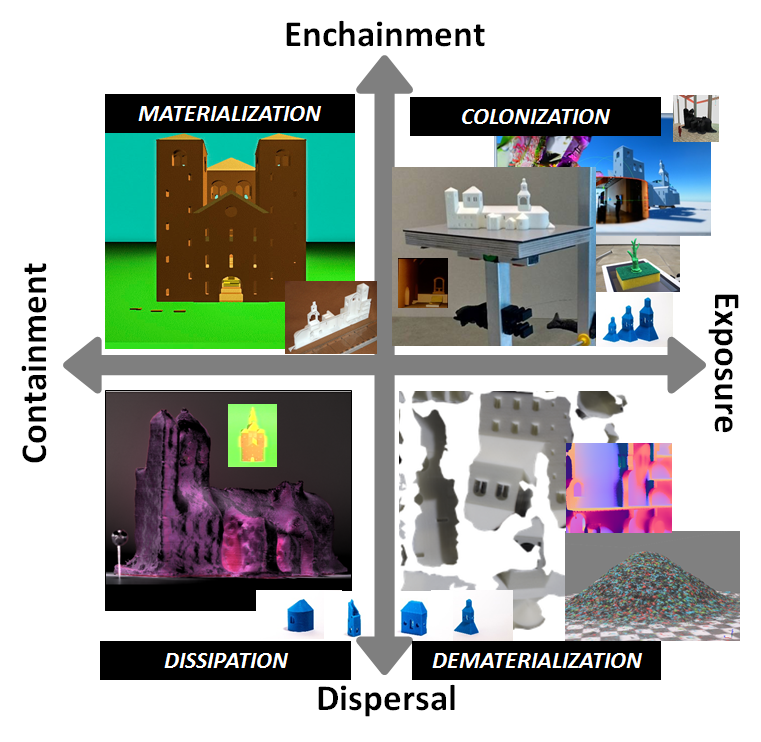

Figure 3: Modified Enchainment versus Containment Grid of Forces (after Lucas 2012, Fig. 16, p.213)

As Lucas (2012, 204) observes, ‘[a]lmost all, if not all, objects are strictly speaking residues of prior assemblages’. He deploys two analytical frameworks he describes as ‘grids of forces’ in order to inject theoretical depth into the study of archaeological assemblages: the first grid analyses permeability versus persistence, the second allows us to investigate the tension between the forces of assembly versus disassembly. It is this latter grid of forces operating on assemblages that our collaboration is currently most concerned with. Within this framework (see Figure 3) Lucas’ focus of attention is firmly on the tension between the processes of (re)materialization and dematerialization (Lucas 2012, p. 213, Fig. 16). However, Reilly (2015a) also foregrounded the two other active forces operating in the complimentary spaces of this framework. Colonization and dissipation also have vital roles to play within assemblages, principally in reconfiguring or extending them, particularly in the phygital. Colonization is shaped by the dual processes of enchainment (also described as coding, or citation) and exposure (or deterritorialization). This force maintains the material coherence of the assemblage even though it might be displaced, perhaps far away, in time and space from its original setting and meaning. However, the vastly accelerated rates of recursion and residuality enabled in the phygital nexus opens up the possibility of uncontrollable mutations and glitches, both miniscule and major, and other accidents of context or reproduction (e.g., Virilio 2003; Minkin 2016). Colonization can thus radically reconfigure the topology and boundaries of assemblages. By contrast, the entropic force of dissipation harnesses the twin processes of containment and dispersal, meaning that elements of an assemblage break up and disintegrate, but largely remain close to their original setting. Whether or not the assemblage is subject to the processes of containment or deterritorialization, persistent components that transfer into new contexts and assemblages can also be considered both ‘itinerant objects’ (Joyce and Gillespie 2015) and residuals.

‘Residuality’ refers to the phenomenon of objects, fragments or materials that persist and reoccur in contexts other than those they originated in (e.g., Brown 1995; Lucas 2017).

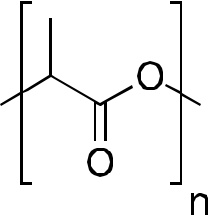

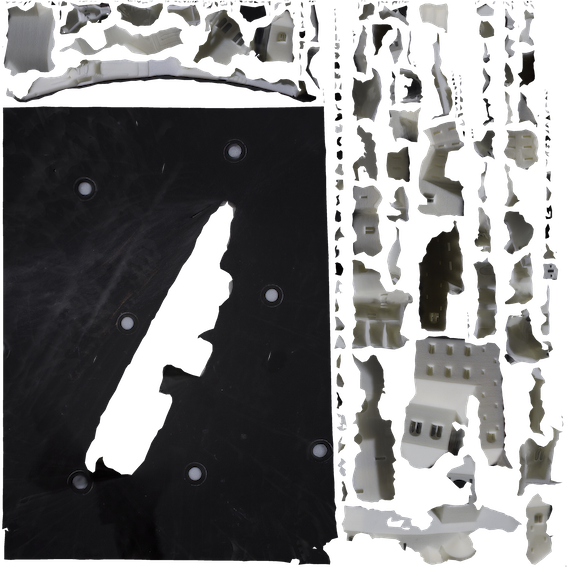

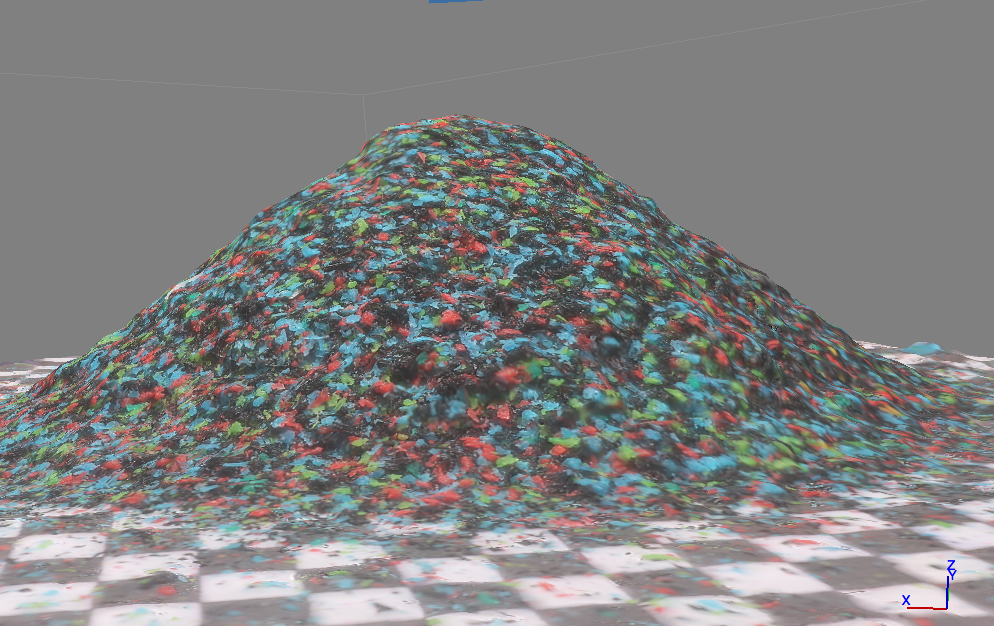

Figure 4: PLA spoil heap - a study in phygital Disassembly/Assembly

Residuality introduces an element of stochastic variability into assemblages as new relational properties, and alternative agentic impact may develop depending on the (re)configuration of their components (e.g., Figure 4) and the particular capacities and agencies of the elements from which it is composed (see Hamilakis and Jones 2017; Jones 2018, 23).

Some things last longer than others and may acquire quite extensive biographies. Pottery and plastics, for example, are particularly persistent and are constantly being dug up from one context and removed into new ones. Consider the sinking of a well. The excavator cuts through pre-existing deposits redepositing materials from earlier temporal horizons into subsequent, increasingly messy, assemblages and contexts containing (re)mixed, or reworked, components originating from multiple temporal horizons. In this shift of context some residual objects within the assemblage may experience ontological transformations. For instance, a flat, circular ceramic object may originally serve as a plate, but if it is broken its material residues - principally sherds - can start to disperse. Every residual object has the potential to become a fresh component of one or more subsequent new contexts in which the ceramic material might become, for example, pieces in a mosaic, or rubbish items in a pit, rubble in a trampled floor, packing material in a posthole, and archaeological evidence.

The residual objects outlined above are more or less materially persistent. Their shape may have been radically altered, but some of the original material they were composed of is still present. However, sometimes it is only the form of the object that persists, while the material in which it was previously instantiated is recursively replaced. Reilly (2015a), for instance, traces different objects made from the voids encountered at Pompeii (e.g., casts, effigies, pseudomorphs, skeuomorphs and 3D prints, amongst others). The recursive, or self-referencing, component here is the form of the original or prototype. Consider the maintenance of an ancient church. Over the centuries elements of the fabric and furniture of the building degrade and must be replaced. Probably every major minster still in use in Europe has a team of masons replacing elements of the persistent conformation we share with previous generations, but using freshly quarried stone.

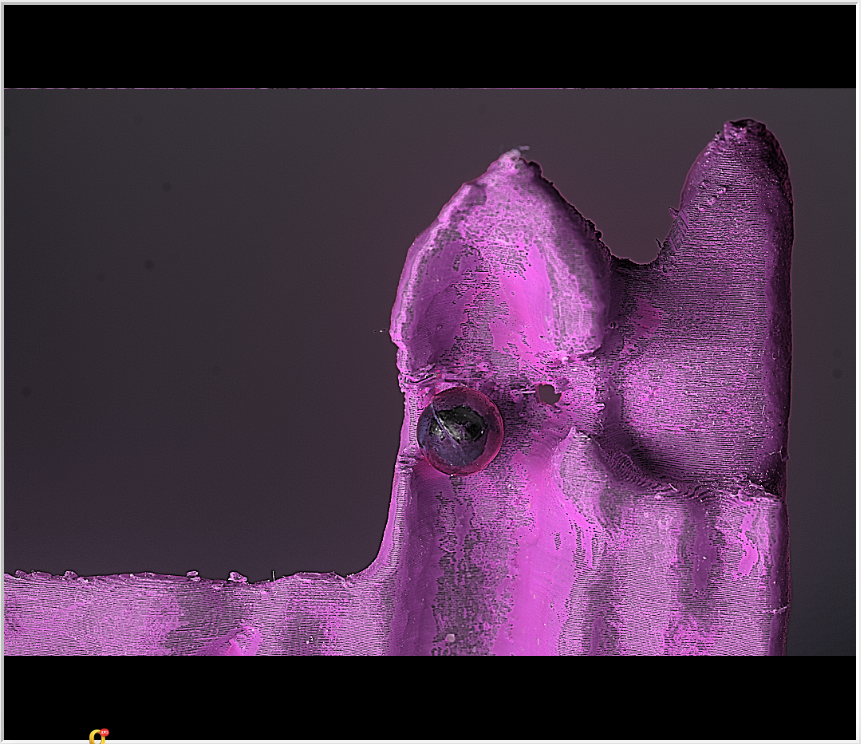

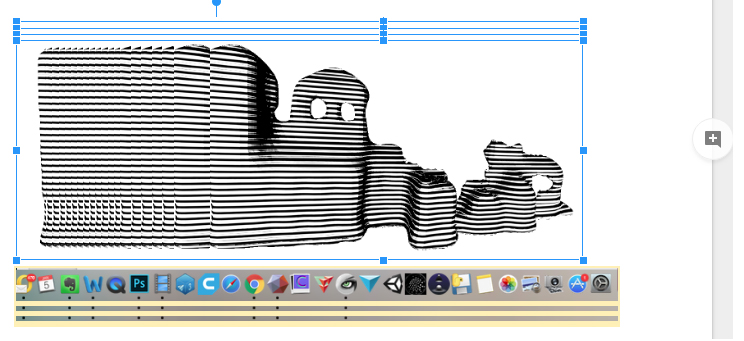

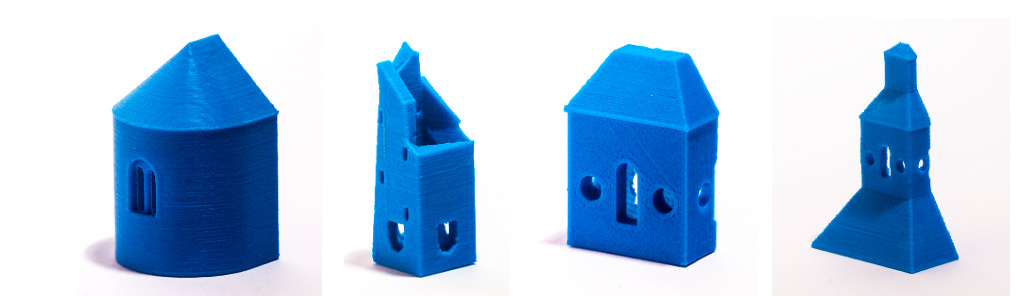

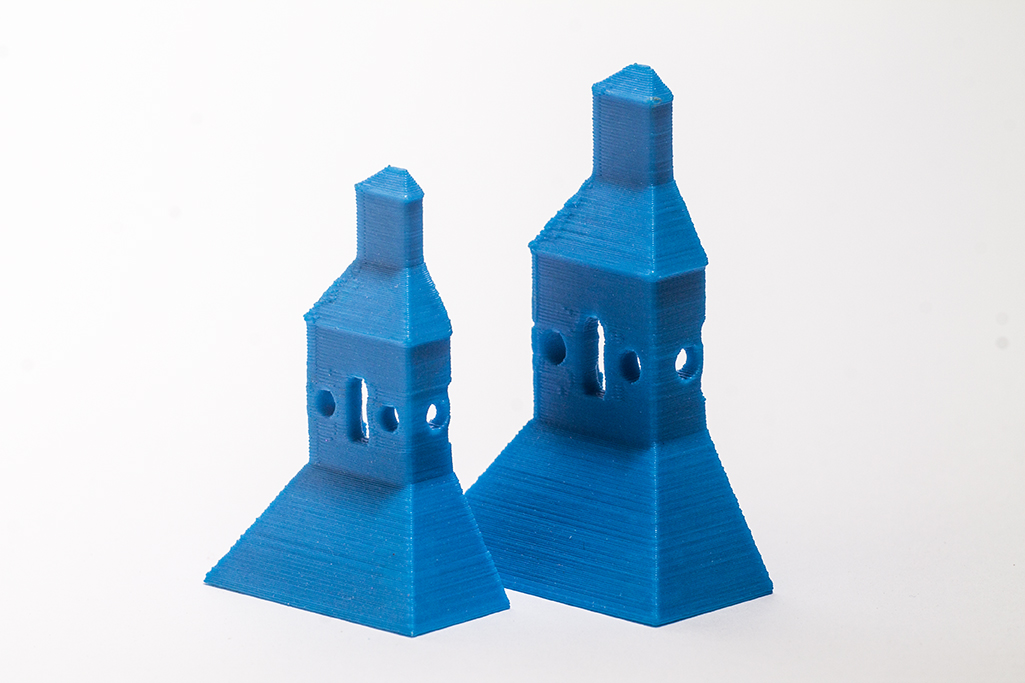

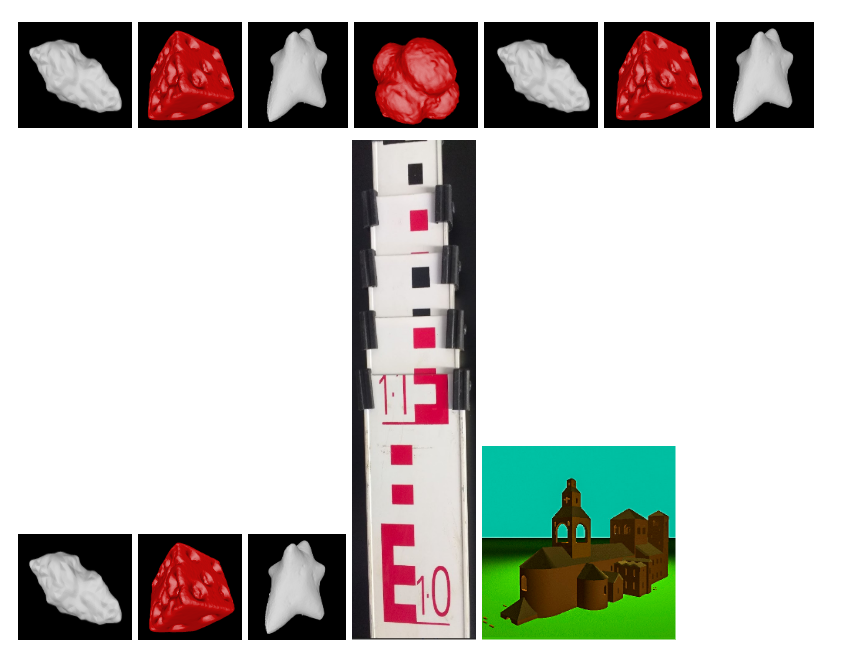

Figure 5: PLA reprint iteration 3. Figure 6: UV fragments II

Phygital assemblages can be both, or either, residual or recursive in nature, since phygital objects are easily replicated, aggregated, augmented, resampled, processed, or transcoded into other formats, and can be redeposited in different materials and at different scales (e.g., Figures 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 & 9). Moreover, dimensions can be flattened (e.g., Loyless 2019), and planes turned (e.g., Figure 9), recalling the strange loops and paradoxes of the recursive structures and processes that fascinated the likes of Gödel, Escher, and Bach (Hofstadter 1979).

Figure 7: Hack Minster Hoard

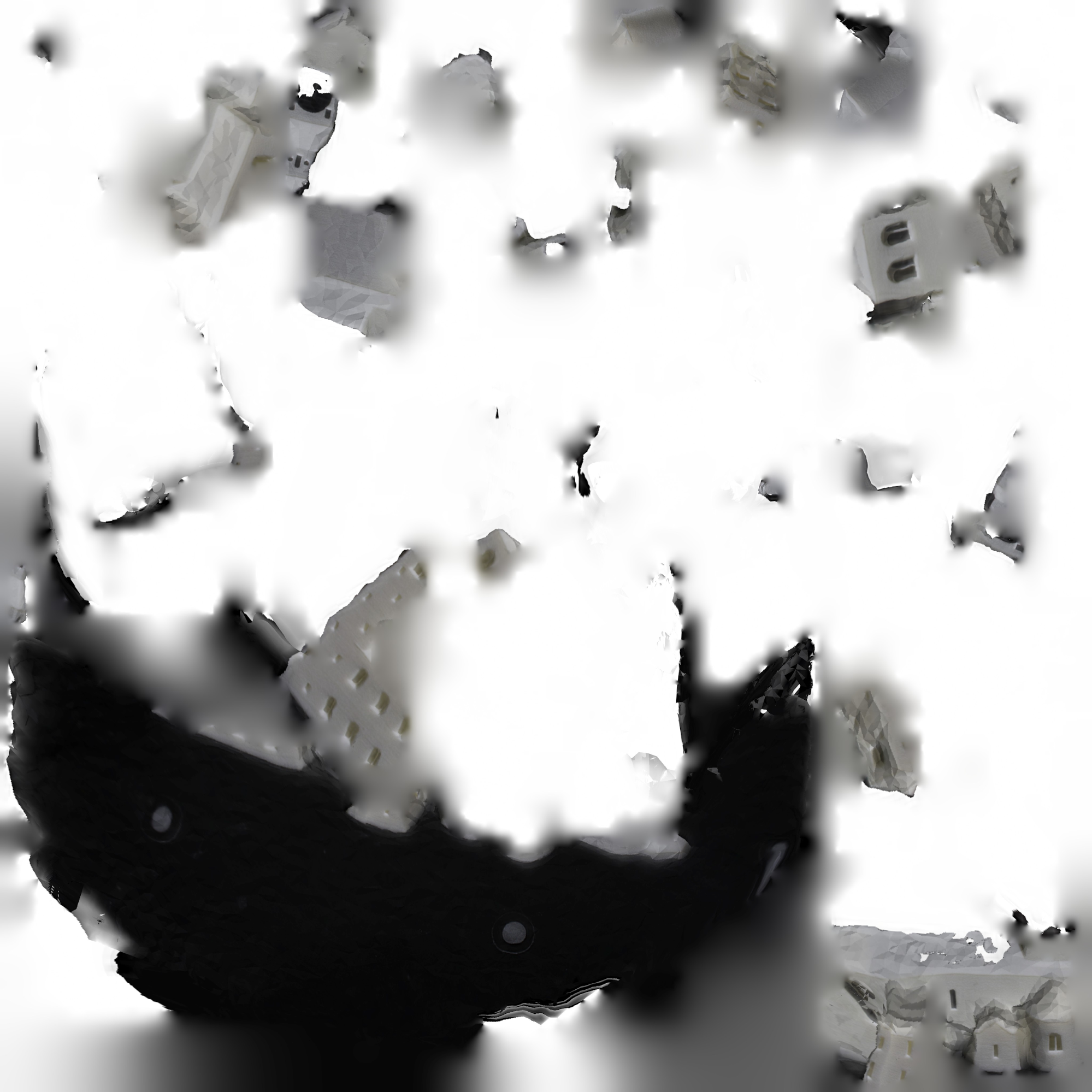

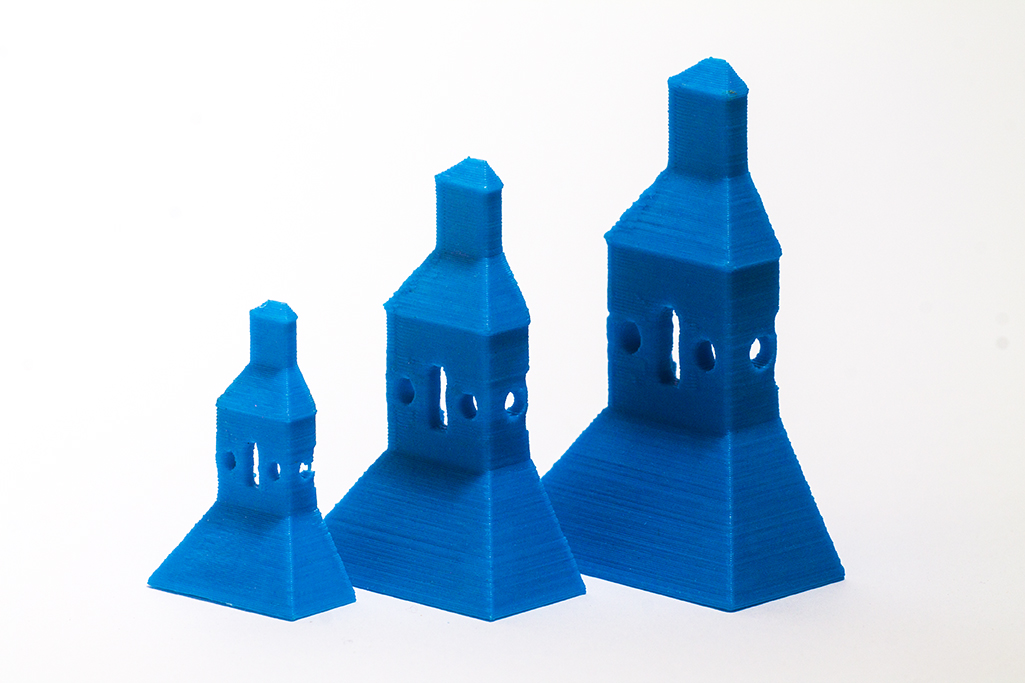

Figure 8: Scale as recursion +/- 1

Figure 9: Stair of churches

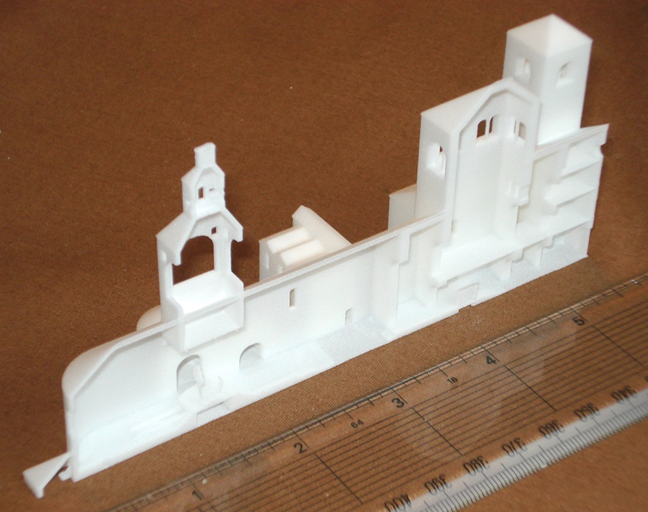

Thus extended, these phygital assemblages are susceptible to new kinds of exploration and analysis, and may be productively recontextualized, reiterated, (re)materialized, reconceptualized, re(con)figured, and (re)discovered. For instance, a digitally rendered edifice may at one moment shrink away as the virtual explorer flys - angel-like - around it, but in the next instant the virtual pedestrian explorer can be enveloped by the interior of the same so-called ‘solid’ model. Both journeys can also be endlessly transformed by adjusting lighting schemes and the resolution used. Equally, the identical digital solid model definition code may produce a 3D material print. Here too myriad perspectives disclose themselves and new registers of intra-action emerge. At one end of the scale, such a physical model might be 3D printed as a hand-holdable and discoverable plastic miniature which could furnish a small-scale diorama. At the other, it is also theoretically possible to 3D fabricate the same digitally defined assemblage in almost any material (e.g. Figure 10), or indeed multiple, or composite, materials, at any scale, including life size (Reilly 2015b; 2015c).

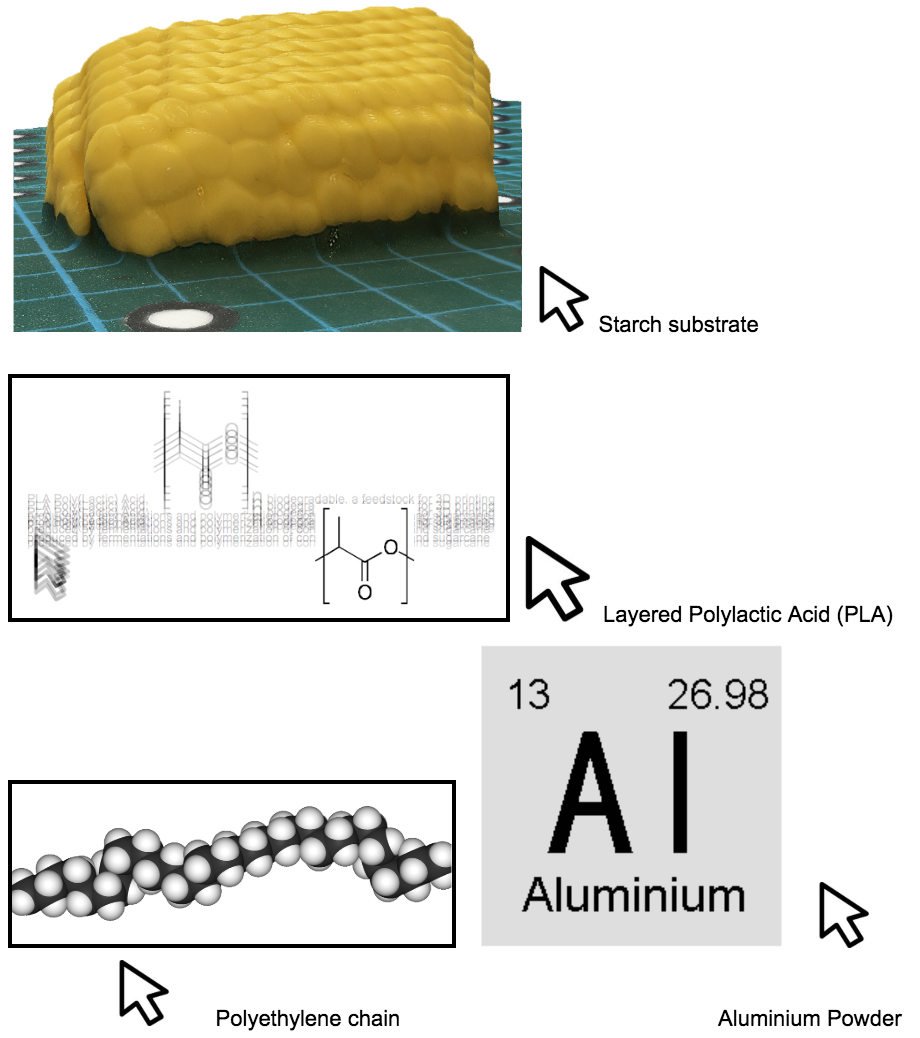

Figure 10: 3D printing deposits

Figure 11: Plastic Print derived from aggregated images of the Devil's Chair, Avebury (Louisa Minkin 2015, with permission)

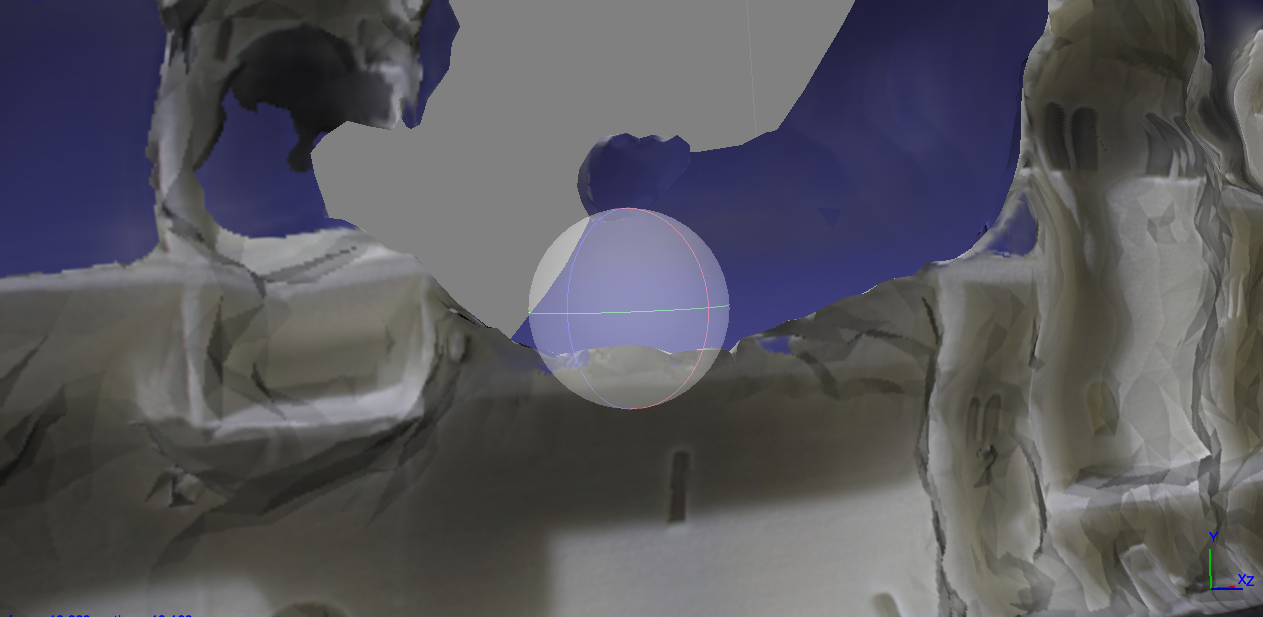

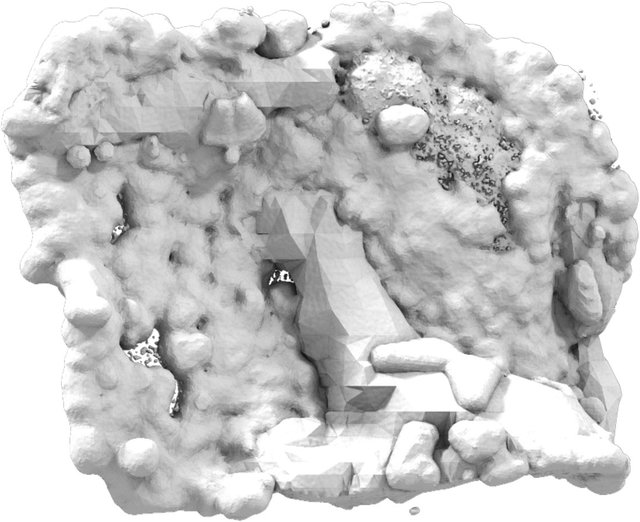

Many other ontological transformations abound in the phygital and can occur in very rapid succession. Consider Louisa Minkin’s Plastic Print derived from aggregated images of the Devil’s Chair, Avebury (2015). For this piece (reproduced in Figure 11), Minkin aggregated images taken by tourists adopting the same pose at this iconic megalith over many years to produce a 3D material ‘souvenir object of uncertain spatio-temporal status’ (Minkin 2016, p.122, & figure 3, p.123). This disturbing temporal-frankenstein-like simulacrum is also a phygital coloniser. Reversing the same technology flows, born-digital physical instantiations can break back into the virtual realm via computational photography, such as photogrammetry (Figure 12 & 34) or Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) (e.g., Figure 13), and a rapidly expanding assemblage of other scanning technologies. Such apparatus has been characterised by Jeremy Huggett (2017) as ‘cognitive artefacts’ that encapsulate hidden recursions of the practices, techniques, calculations, and interventions that help us explore, reveal, capture, and characterise archaeological objects (see also Jones 2002; Latour and Woolgar 1986). Black-boxes or not, such instruments (of colonisation) are now commonplace in both archaeological (e.g., Beale and Reilly 2017; Graham 2018; 2019; Jones and Díaz-Guardamino 2019) and artist practice (e.g., Beale et al. 2013; Minkin 2016; Petch 2019; Dawson in press). However, all DSLR images and digital scans are based on point measurements and no matter what resolution is adopted they are still only digital surface samples, and consequently always considerably less than the original subject under examination (Carter 2017). When such point readings are interpolated into meshes for 3D renders or 3D printing a significant proportion of these sampled data are discarded algorithmically. In other words more detail is being lost with each new recursive rendering, print or scan. We also explore this phenomenon in our collaboration which presents itself in second or third generation print-outs as a gradual softening of form as once sharply defined conformations are digitally eroded (e.g. compare Figures 5 and 17).

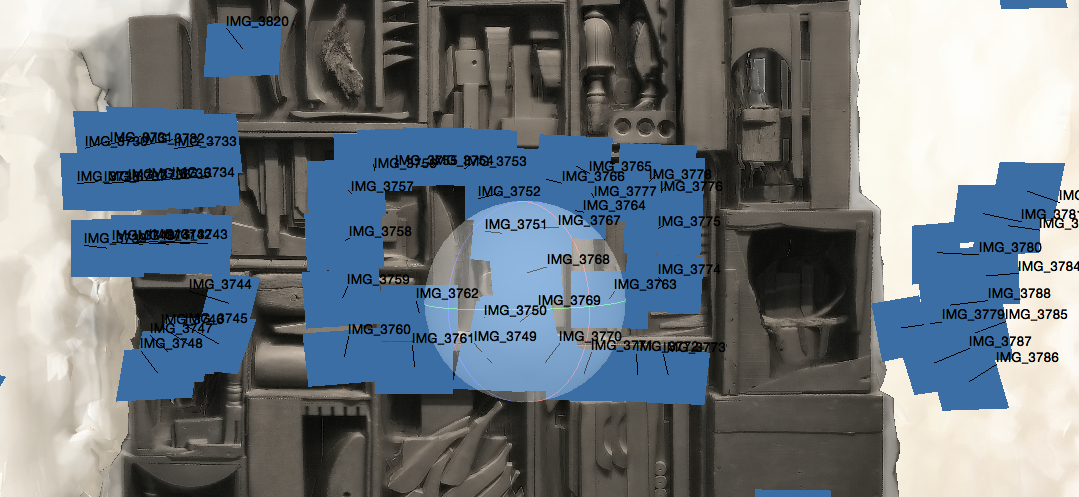

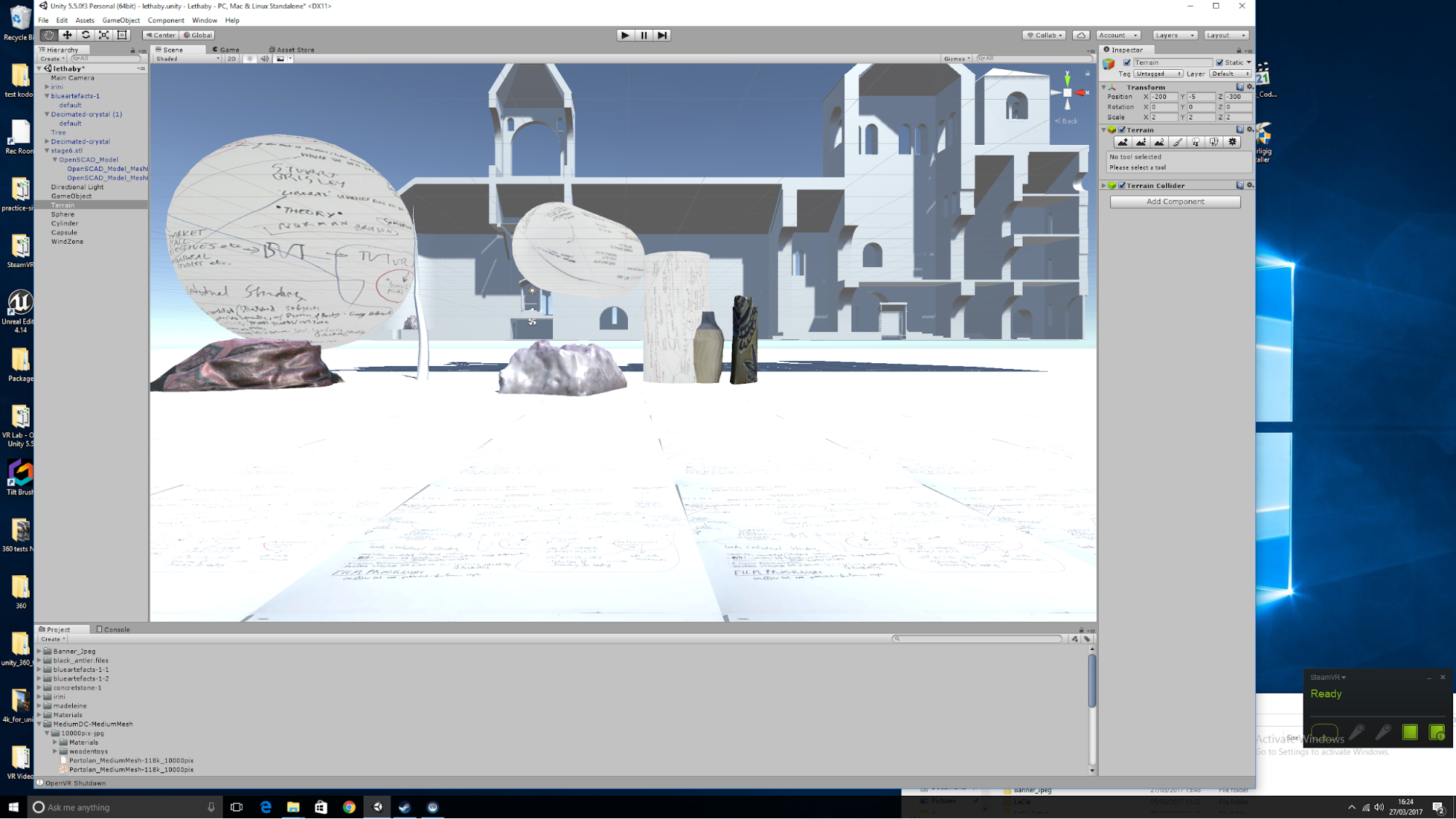

Figure 12: Double assemblage

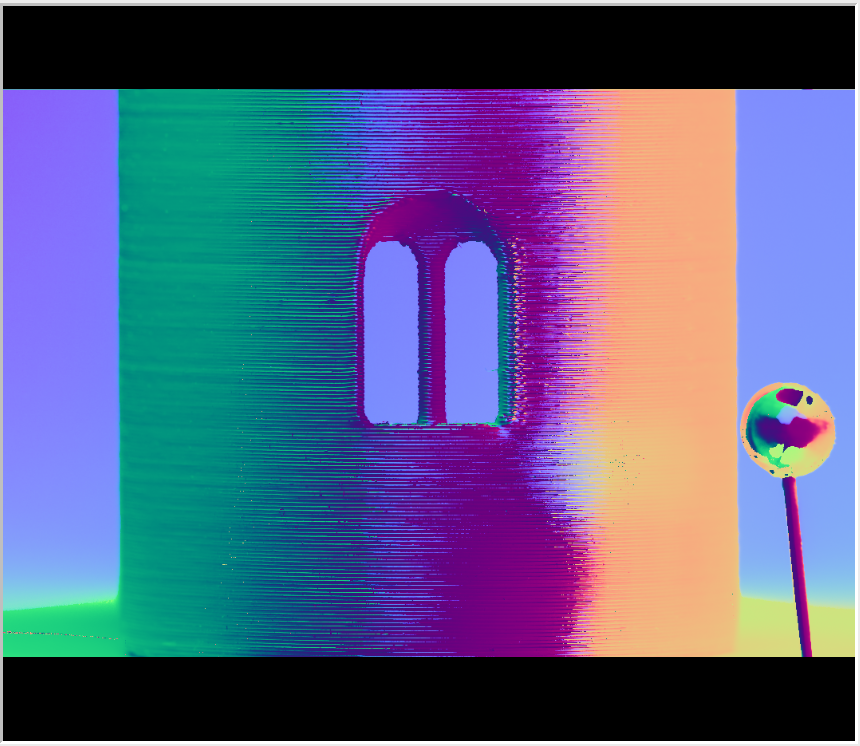

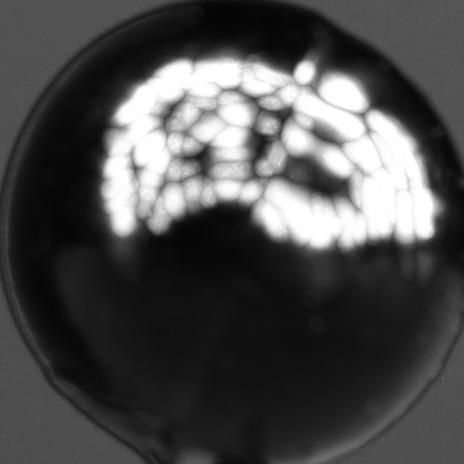

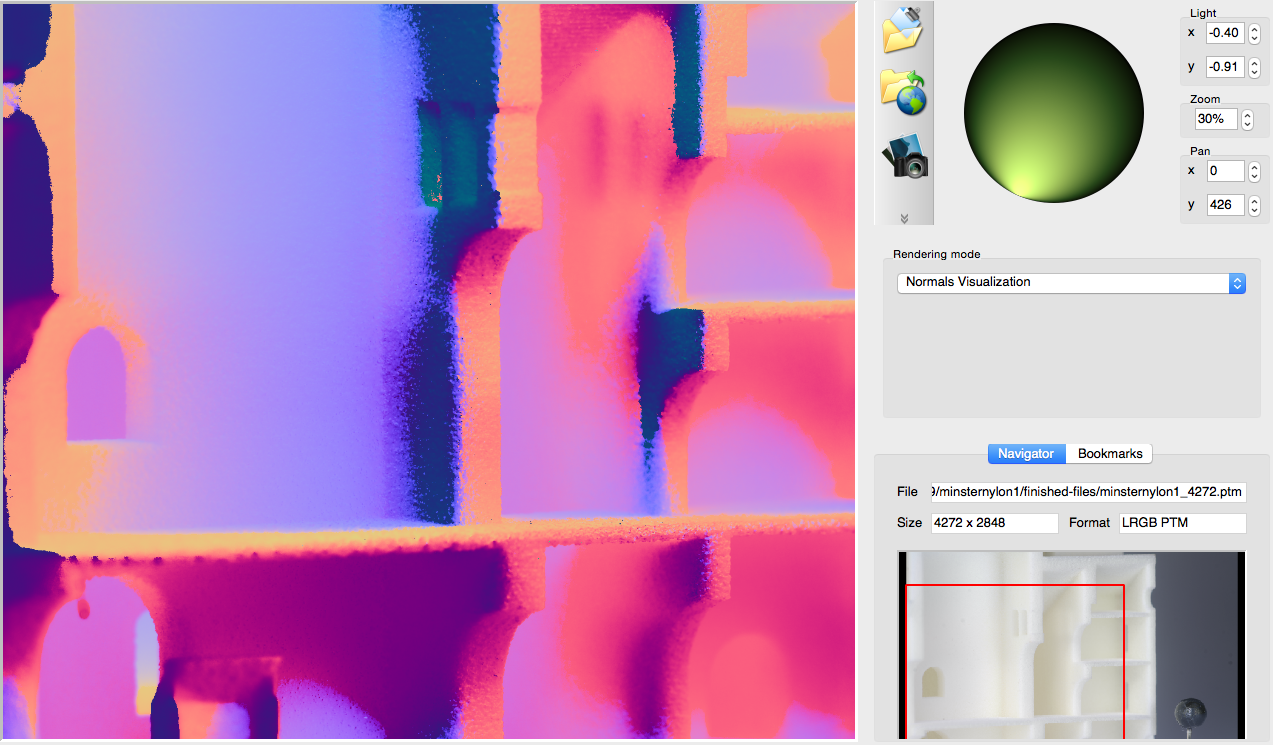

Figure 13: Triple spoof chameleon architecture: interior RTI image of a 3D print of an archaeological Constructive Solid Geometry (CSG) modelled re-imagination of a building annihilated in CE 1093/4

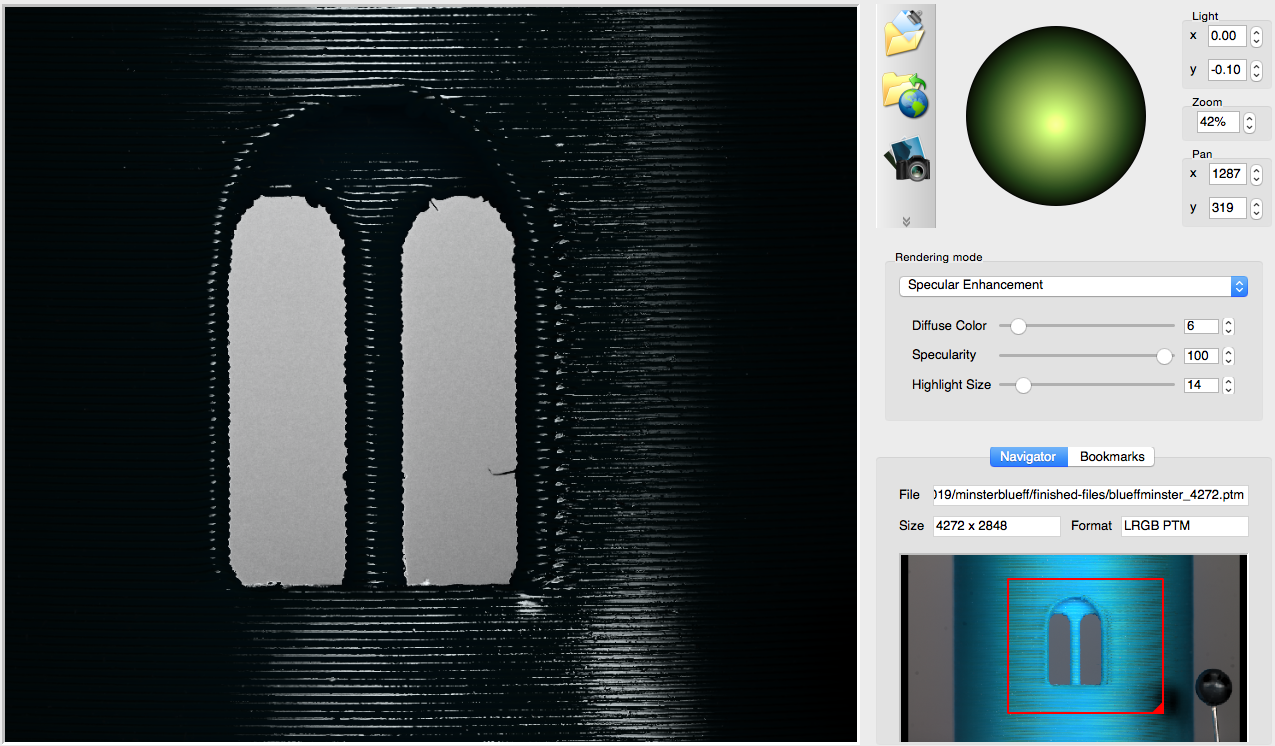

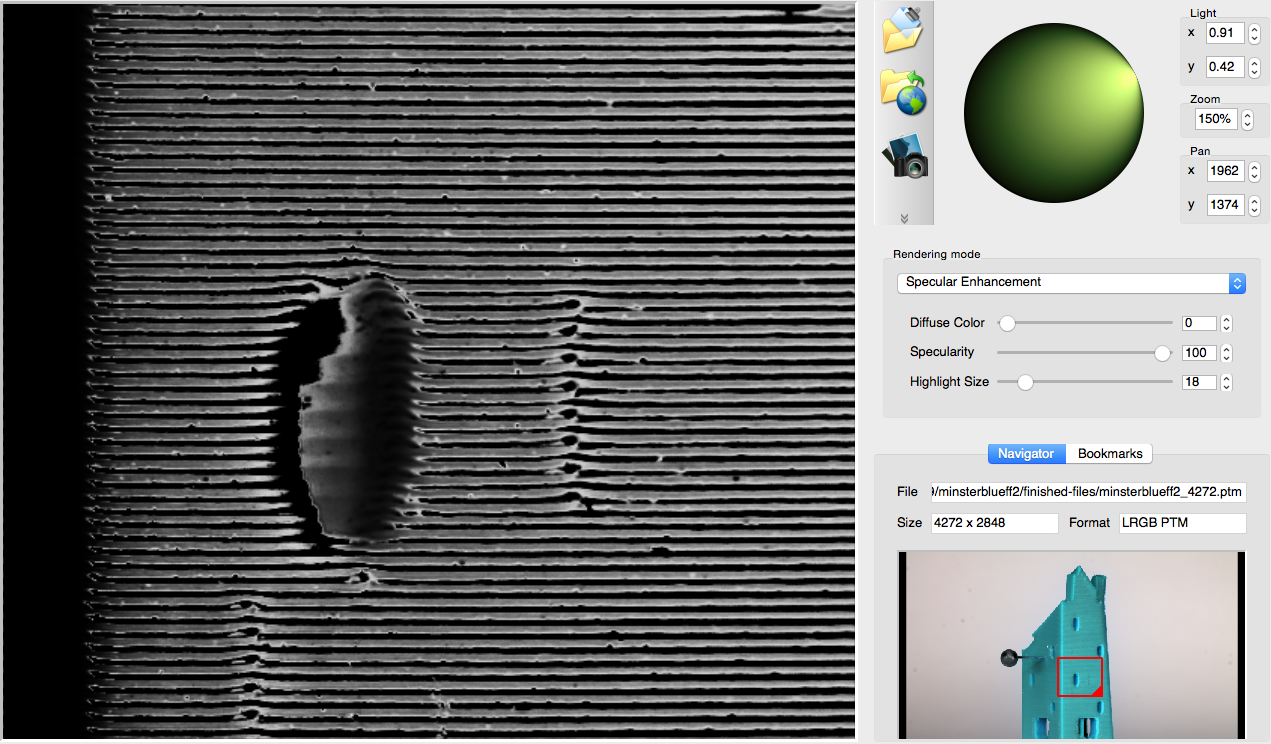

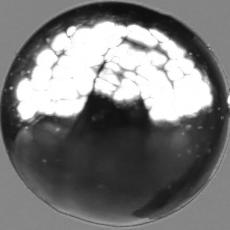

Many of RTIs featured in this essay virtually (re)presence a 3D printed re-imagination of the digital Old Minster of Winchester. RTI is a computational photography technique in which known lighting information derived from multiple digital photographs is mathematically synthesised to build a model of the subject’s surface shape and properties (3). However, as Andy Jones and Marta Díaz-Guardamino (2019, 213) make clear, “[i]t would be a mistake to assume that RTI images were simply photographs; they are ontologically complex composite constructed images, with a certain kinship to the photographic”. In a sense, the initial geometry and surface properties of the object of study retreat, or dissipate, into residual ‘surface normals’ and morphing shadows as the RTI algorithms generate a kind of mathematical mirage, yet another recursion accompanied by another ontological shift, and representing a second or third order ‘spoof’ of the initial geometric re-imagination (Figure 13).

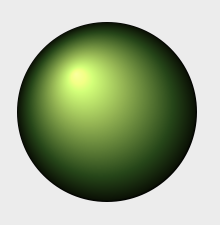

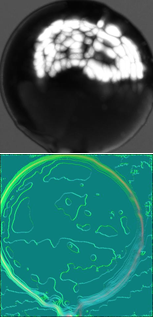

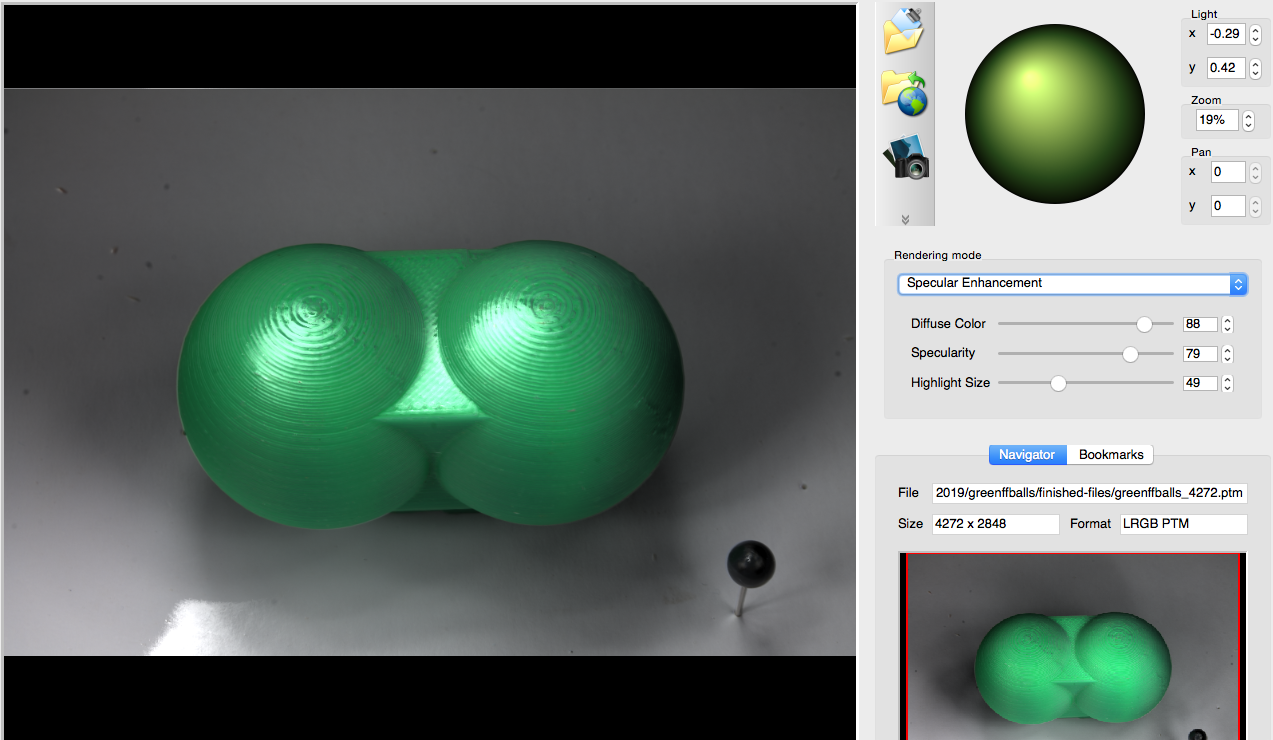

As viewer, subject and RTI parameters playfully intra-act, the on-screen mirage is continually reinvented, chameleon-like, producing a stream of surrealist visualisations, radically altering our apprehension of light, space and surface(4). For example, applying specular enhancement to a previously dull matt surface has the effect of shining harsh raking lights across a now shiny surface, producing almost haptic highlights and shadows (e.g., Figure 14), which can often reveal surface information that is not immediately disclosed under direct empirical examination of the original physical object or, indeed, the individual initial digital photographs. Key to the production of RTIs is the inclusion of a highly polished sphere in the assemblage; the highlights produced on the sphere by each differently positioned flash of the strobe are used to derive the surface geometry of the subject of study.

As viewer, subject and RTI parameters playfully intra-act, the on-screen mirage is continually reinvented, chameleon-like, producing a stream of surrealist visualisations, radically altering our apprehension of light, space and surface(4). For example, applying specular enhancement to a previously dull matt surface has the effect of shining harsh raking lights across a now shiny surface, producing almost haptic highlights and shadows (e.g., Figure 14), which can often reveal surface information that is not immediately disclosed under direct empirical examination of the original physical object or, indeed, the individual initial digital photographs. Key to the production of RTIs is the inclusion of a highly polished sphere in the assemblage; the highlights produced on the sphere by each differently positioned flash of the strobe are used to derive the surface geometry of the subject of study.

Figure 14: Specular RTI Balls

Jude Jones and Nicole Beale (2017) have foregrounded the performative nature of RTI and, indeed, another significant set of performative recursions is captured through the mirror-surface of the sphere with every strobe of the flash. During each of these entangled intra-actions, the 3D object, the camera, the flash, the reflective sphere itself, and the photographer (archaeologist/artist) mark one other with residual traces of light. In fact, the recursive reflections caught in the surface of the sphere create the total assemblage’s spontaneous and co-authored signature. The entangled traces of light embedded in the RTI may also be conceptualised as auto-archived paradata(5) (Bentkowska-Kafel, Baker and Denard 2012) recording the circumstances, environment, relative position, poses, and the condition of all the actants and their intra-actions in this emerging polynomial assemblage as it unfolds from frame to frame (Figure 15).

Figure 15: Meeting the assemblage halfway performance with auto-archived paradata

In summary, by placing assemblages within a phygital nexus, we open up fresh possibilities for digitally creative disarticulations, repurposing, and disruptive interventions (see Bailey 2017), offering phygital ‘acts of discovery’ beyond the spade, pencil, brush, leaf or the screen (see Edgeworth 2014), and in so doing unleash new potential for novel and, perhaps, productively provocative conceptions of residuality and recursion.

In the next section we develop our case study: the extending phygital assemblage of the Old Minster of Winchester.

Initial residues and recursions of the Old Minster of Winchester

In CE 1092, the Anglo-Saxon cathedral of Winchester known as the “Old Minster” was probably the most imposing building in pre-Norman Britain. However, in 1093/4, the Old Minster was completely obliterated to make way for the construction of the Norman complex we can still visit today. A substantial part of the site of the Old Minster was excavated by archaeologists in the early 1960s who discovered that this once imposing ecclesiastical edifice had been entirely dismantled down to, and including, its foundations (Biddle 2018; Kjølbye-Biddle and Biddle forthcoming). Indeed, by 1963, the only trace of the Old Minster was it’s footprint and some rubble, captured by the robber trenches left and subsequently buried after the Old Minster’s foundations had been removed at the end of the 11th century. A decade after these excavations had closed, the principal archaeological investigators wanted to convey the scale and form of the Old Minster to the general public in an easily accessible way. They turned to what was then cutting-edge digital technology and, in 1984-6, several software encoded models describing distinct phases in the development of the Old Minster were created and rendered using IBM proprietary experimental solid-modelling software to produce the first digital recursions (Reilly 1989; 1992; 1996).

Expanding the Old Minster Assemblage into a Phygital Nexus

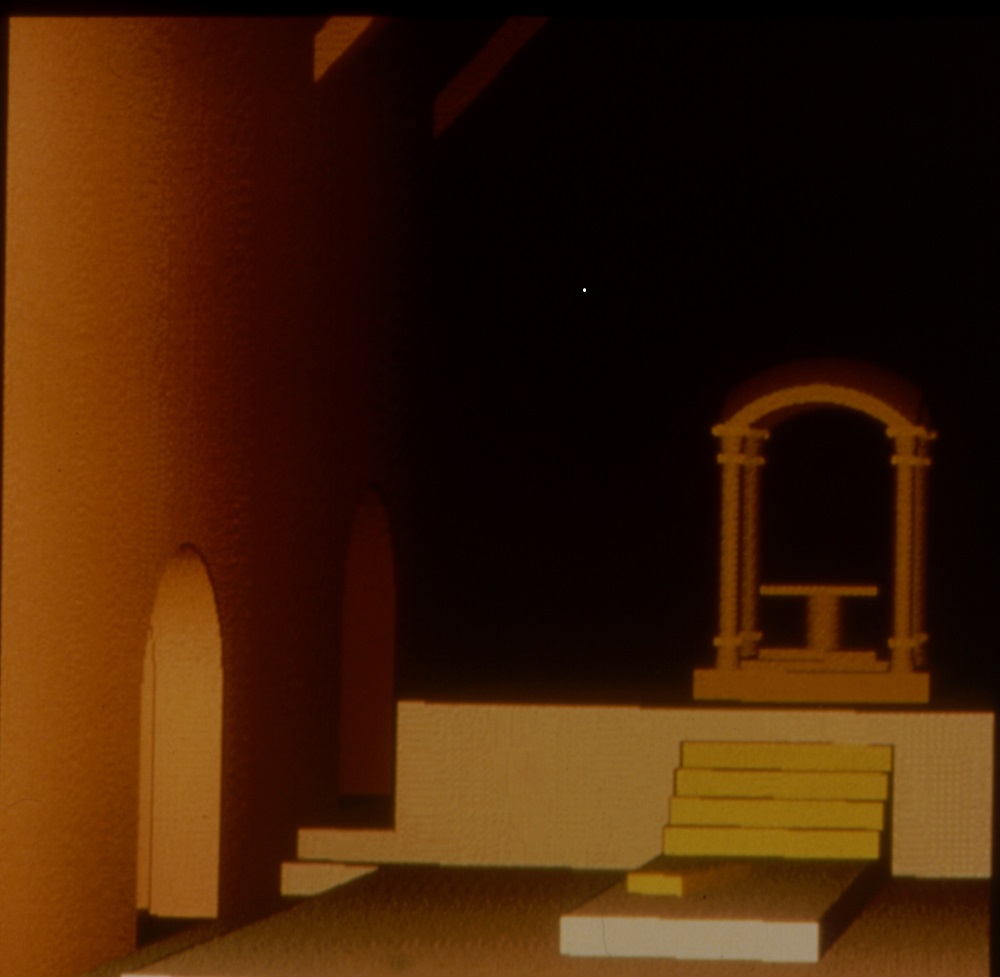

By recursively generating single view static images (‘frames’) from incremental simulated viewpoints (e.g. Figure 16) the world’s first computer-animated virtual tour of an archaeological re-imagination emerged. Versions (further recursions) of The Old Minster, Winchester ‘movie’ were shown on TV and exhibited at the British Museum, others were encoded in PAL, NTSC, and SECAM and distributed initially on VHS, U-matic and Betamax video cassette (tape) formats, and later using CD and DVD formats burned into the next generation of material substrates.

Left, Figure 16: Old Minster frame, 1984/5. Right, Figure 17: Lossy Old Minster PAL-U-matic-VHS copy

Figure 18: Re-imagined final phase c.1092 Old MInster CSG model using OpenSCAD, 2015

Unfortunately, the only surviving residue of the first minster movie is a JPEG3 recursion of a VHS PAL tape video, which itself was copied from a U-matic video tape master. It serves to remind us that while the initial geometric definition of the re-imagined Old Minster may have been orthothetic in nature (Stiegler n.d.), each instantiation, re-registration (e.g. scan, JPEG photographs, video, or 3D print) and, more often than we might realise, every time such digital instantiations are compressed for transmission a degree of digital decay or entropy is introduced (e.g., Figures 17, 21 & 22). With each new codec decoding/encoding recursion the video image resolution was decreased, and more information dissipated through the inherent lossyness of each successive encoding (see Horowitz 1998; Cubitt 2014, 249).

Figure 19: Initial phygital Old Minster, 2015.

However, as technology advanced, the experimental software, hardware and distribution media standards that the digital Old Minster model was built on became obsolete, and the models retreated into the background. Actually, the makers thought them to be lost. However, in 2015 residues of the digital Old Minster in the form of the original proprietary model definition files were rediscovered buried within layers of unsupported experimental code and recovered (6). Fortunately, although the models were written in a dead language, these seminal virtual artefacts could be restored and reaccessed by translating them into a modern orthothetic definition using open source code (7) (Figure 18). Such open code and digital technology offers many new and productive affordances for exploring and recontextualising the digital Old Minster. For example, besides supporting virtual settings in interactive graphical contexts (e.g., programbits.co.uk/minster/minst.html), the same digital objects can be explored in VR (e.g., Figure 29) or materialised in different and multiple materials as 3D prints (Figure 24), effectively moving the setting off the screen and onto the stage as it were, and giving substance to digital objects which would otherwise be, as Monika Stobiecka (2019) wryly puts it, ‘deprived of their matter’. Critically, in this latest ontological shift, we gain multisensorial, multimodal, and embodied experiences with tangible objects of increased cognitive depth.

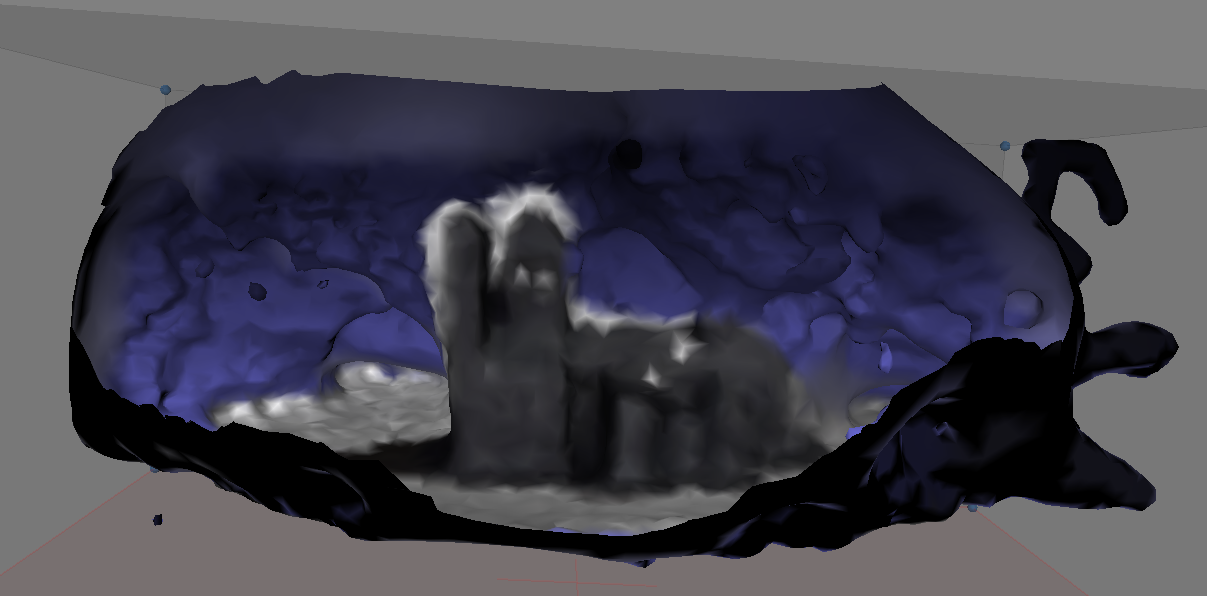

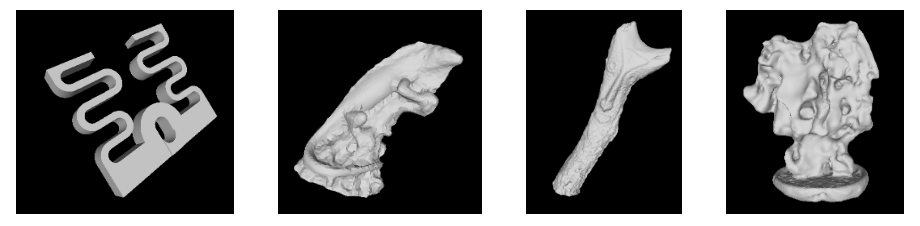

The digital Old Minster is thus an expanding, constantly morphing, ontological assemblage of (im)material digital objects within our phygital nexus. To recap, its geometric properties were initially presented virtually, that is on screen using ray-casting algorithms, but decades later the same geometry was instantiated as a material 3D print. As we have already observed, 3D prints, like any other artefact, can be photogrammetrically (re)captured or scanned and (re)virtualised as, for example, point-clouds or mesh recursions which can in their turn be (re)deposited and recontextualised (e.g., Figures 20, 21, 22, 23 & 24).

For the remainder of this visual essay we will intra-act with several ontological assemblages drawn from the phygital nexus of the digital Old Minster.

Figure 20: Phygital Old Minster Synthetic Sundial (RTI GIF 3D )

Figure 21: Old Minster section RTI Mirage (RTI and RTI GIF detail)

Figure 22: Dissipating Phygital Old Minster v.3 (RTI GIF 3D print)

Figure 23: Messy Ontological Assemblage Collage

Further Recursions and Residues: Exhibitions

Throughout this collaboration, our interdisciplinary (art/archaeology) conversation about assemblages has been, and continues to be, syncopated with exhibitions in which we attempt to distil some of our insights into art forms, and yet further recursions and residues from prior assemblages. Like the assemblages we feature, our commentary is messy, as we interject our reflections using a combination of text and collaging.

Sightations, TAG 2016, Southampton (19.12.16 –21.12.16)

Curated by Joana Valdez-Tullett, Helen Chittock, Kate Rogers, Eleonora Gandolfi, Emilia Mataix-Ferrandiz, and Grant Cox

The Sightations exhibition (10) at the Theoretical Archaeology Group conference held at the University of Southampton in December 2016 provided an important focal point where art and archaeology practices could come into constellation. The work featured by Ian Dawson was called ten (Figure 24).

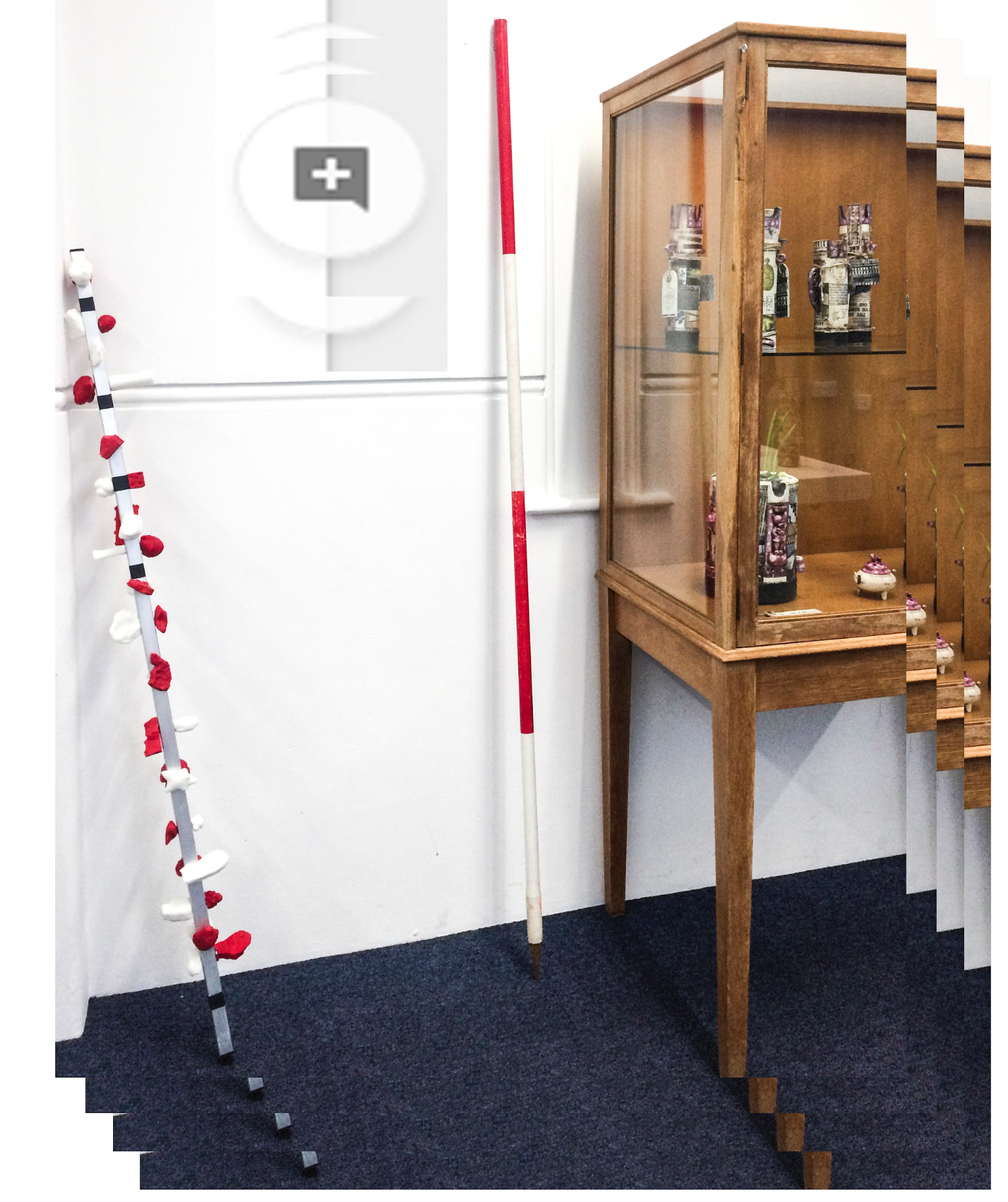

Figure 24: ten (Ian Dawson, 2016, Aluminium, fused filament 3D prints and ranging rod)

Despite being exhorted by an artist ‘not to over analyse it’, it is difficult for an archaeologist not to respond to ten other than as a treatise on archaeological excavation recording. At a distance, the succession of red, white and black marks, evenly distributed down the length of the square-profiled aluminium bar, shouted out ‘levelling staff’ - a surveying companion on many excavations. The juxtaposition with the 2m red and white ranging rod, typically used as a photographic scale on site, reinforces this reading. Looking closer, the archaeological excavation narrative really seems to come alive as the ‘graduation marks’ resolve themselves into well-known artefacts, physical memories, waymarking temporal horizons, being registered by the staff (Figure 25).

Figure 25: ten temporal horizons

Figure 26: (Im)material Old Minster (Winchester) 2016 continued (Fused filament 3D print and printed photographs on paper)

In the same room, Paul Reilly’s featured work was called: (Im)material Old Minster (Winchester), 2016. This piece also alluded to time depth and persistence (Figure 26). The little white mono-material 3D print, fabricated via the web using shapeways.com in 2016, was accompanied by two 2D colour prints of the same digital object as it was rendered 30 years previously, each residual artefact, from different time horizons, a recursion embedded in a shared, but fleeting present, beckoning new residual assemblages to emerge.

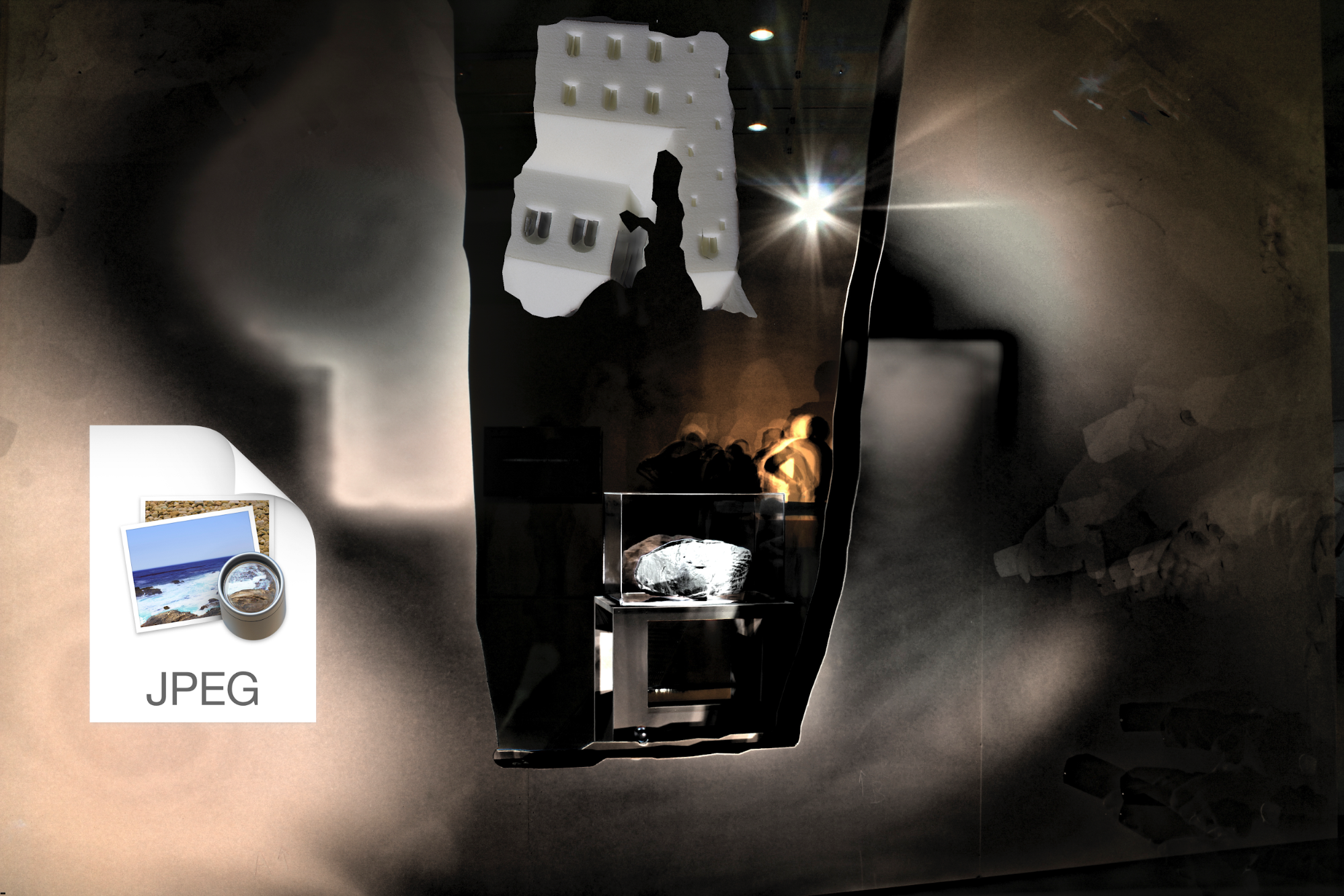

Annihilation Event, Lethaby Gallery London (22.03.17- 29.03.17)

Curated by Louisa Minkin and Elizabeth Wright

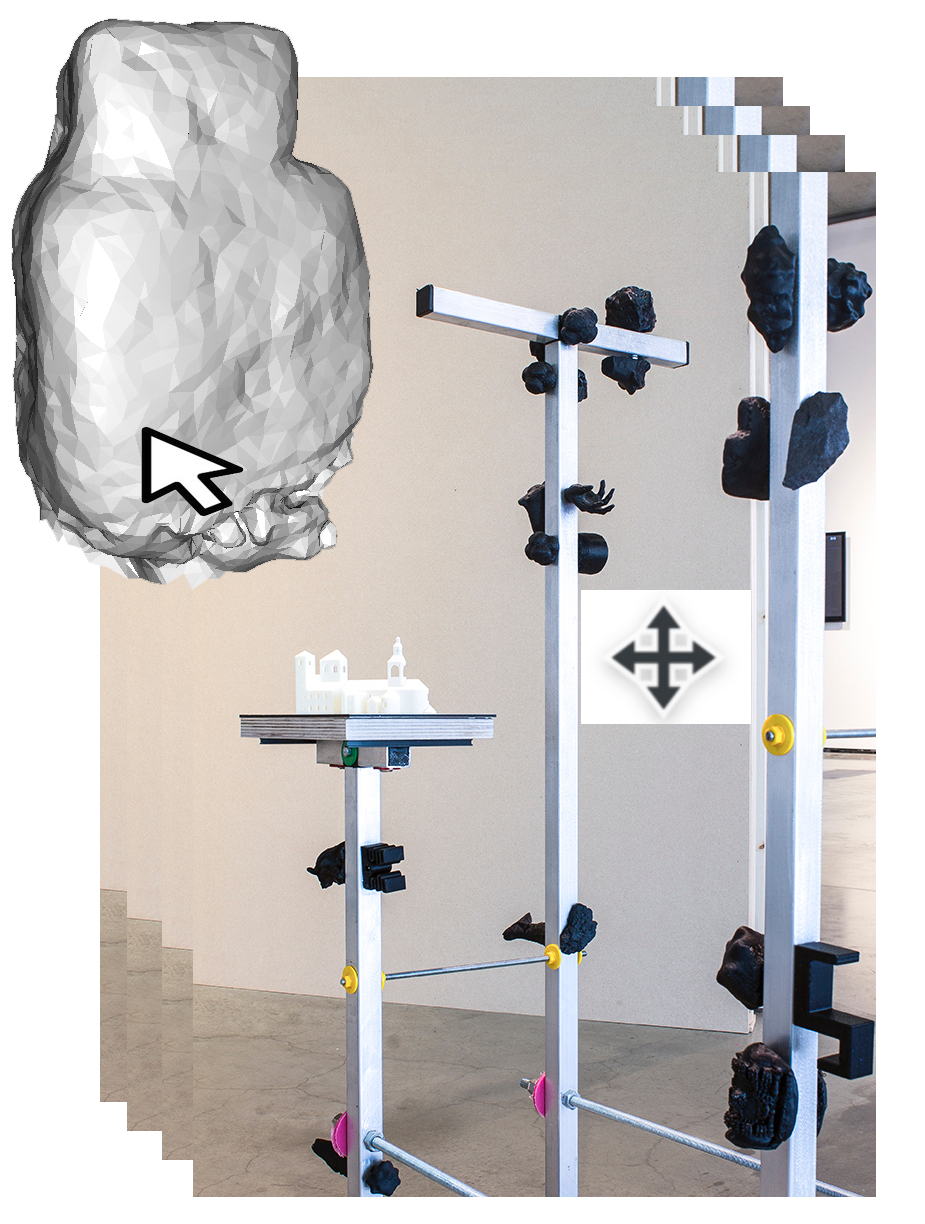

The next opportunity to develop our conversation, was the Annihilation Event, held in the Lethaby Gallery, UAL, London. The assemblage was billed as having “no singular origin, but many strands and streams ... a project about copies, prints, scans, derivations, reconstructions, casts, and virtual models”. The work we featured was titled Digital Old Minster, the archaeology of a digital file (Paul Reilly & Ian Dawson, 2017, Aluminium and fused filament 3D prints). Here aluminium bars affixed with residual 3D printed objects frame the plastic Saxon minster in a rather gothicesque assemblage of gargoyles and flying-buttresses.

Figure 27: Digital Old Minster, the archaeology of a digital file, 2017 (Paul Reilly & Ian Dawson, Aluminium, fused filament 3D prints)

Figure 28: Material prints embodying immaterial code introduce the (im)material grey zone

Figure 29: Recursive Assemblage (exhibition space). Screengrab from Unity VR build, Annihilation Event, 2017 (Louisa Minkin, with permission)

Figure 30: Recursive Assemblage (guest exhibits) Screengrab from Unity VR build, Annihilation Event, 2017 (Louisa Minkin, with permission)

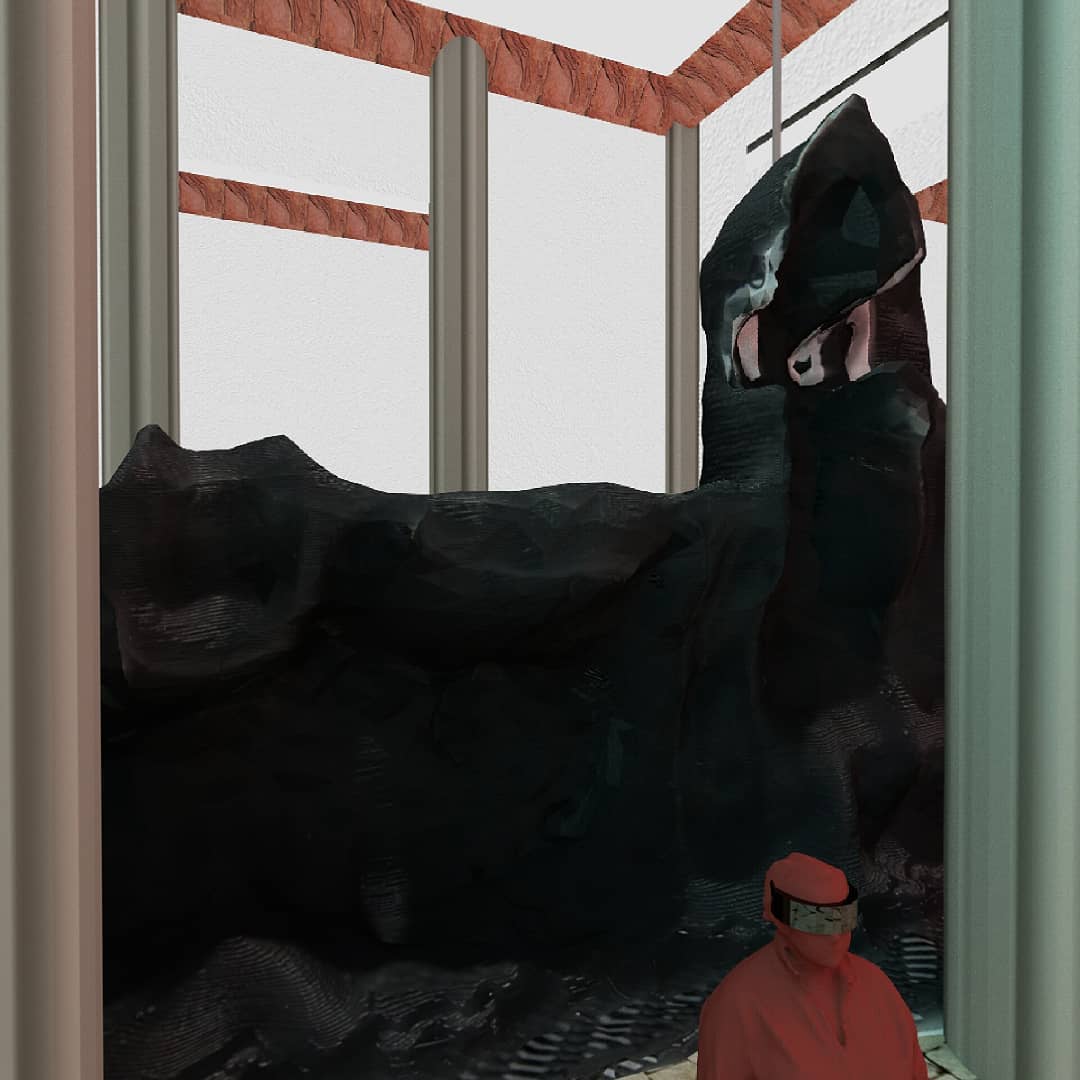

As part of the Digital Old Minster, the archaeology of a digital file exhibit, we extended the assemblage, in collaboration with Louisa Minkin, by creating a virtual reality installation of the Old Minster (Figures 29 & 30). Visitors were allowed to deposit virtual objects within the VR Old Minster, thus creating a recursive exhibition space within the exhibit itself, which was of course also within the main exhibition space, and so producing a kind of Old Minster ‘Tardis’ (9), where space and scale were weirdly warped.

Along the Riverrun, ArtSway, Sway (24.07.17-30.07.17)

Curated by Alex Goulden and George Watson

Figure 31: Old Minster, 2017 (Ian Dawson and Paul Reilly, Aluminium, fused filament 3D prints, digital picture frame, scouring pads, G-clamps, dimensions variable)

Our evolving assemblage was again reconfigured and augmented for the Along the Riverrun exhibition at ArtSway (10). In Old Minster, 2017 a version of the ‘Minster Movie’ is played through a tablet incorporated into this artwork, the looping guided tour endlessly returning to its opening frame. The tablet is laid horizontally, and the viewer needs to lean over to see the screen, but the screen has been partially occluded by a scouring pad, on top of which stands a plastic tree. This seemingly ecceletic assemblage recalls an ‘archaeological site’ prior to excavation; the stratigraphic sequence seemingly lifted whole from the trench and implicating an unseen void of the archaeologist’s trench, pre-translation into very mutable mobiles.

Figure 32: Old Minster, 2017 details (Ian Dawson and Paul Reilly)

Groock’s Gallery, Cyberspace (11.11.18- )

Curated by George Peter Thom

Our most recent collaboration is a cyberpunk piece of conceptual art on display in Groock’s Gallery. This unique cloud-based VR gallery is housed in a converted digital temple, designed around an archetypal building (that is non-archeological), aimed at contemporary participatory mythological practice in cyberspace (11). In this piece, titled “Minster” - Obj with black tone (Paul Reilly and Ian Dawson 2018), the phygital Old Minster has broken back in to the virtual once again.

Figure 33: “Minster” - Obj with black tone (Paul Reilly and Ian Dawson 2018)

Figure 34: A recursive photogrammetric model reconstructed from meshlab screenshots of previous photogrammetric models

Provisional Reflections on a Messy Assemblage

In subverting the phygital nexus, our collage of (im)material art/archaeology has spread across Gavin Lucas’ entire assembly versus disassembly grid of forces, with certain elements participating residually or recursively in several, sometimes overlapping, sub-assemblages where their ontological status is not necessarily settled (Figure 35).

Integral to this reflexive collaboration has been the re-imagination of the Saxon Old Minster of Winchester as it may have looked just before it was demolished in CE 1093. In principle, the geometric definition of any assemblage is immutable and may be retained in digital statis indefinitely. One such geometric hypothesis (the digital Old Minster) went into digital stasis in 1984 when the Old Minster was encoded, as it was then interpreted, in Constructive Solid Geometry modelling software. However, subsequent phygital recursions, and their residues, derived from this specific geometric hypothesis, may be significantly less persistent and more mutable when exposed to the forces of (re)materialization, dematerialization, colonization and dissipation. Crucially, time is required to activate this grid of forces. Without time there can be neither movement nor change. Without movement there can be no dislocations, no adjustments of perspective, and no shift in our thinking. Without change there is no entropy, no decay, no erosion, no exposure, and no room for serendipity.

The first materializations of the digital Old Minster were rather fleeting 8-bit VGA resolution static images rendered on specialist hardware, and more or less contained within research laboratories. However, when these digital images rematerialized on photographic film, using analogue cameras, they became somewhat more persistent and decidedly more mobile recursions. These images could now be shared as 35mm slides for projection presentations or as photographic illustrations in articles and posters. Later, further low-resolution recursions were concatenated and transformed into highly choreographed animations that could be transmitted to wider audiences. The introduction of apparent movement into the mix had the side effect of permeating the entire assemblage with time and duration. Time enables new types of relationships to emerge between actants. In particular it causes a subtle, yet profound, shift in the relationship between the artist/archaeologist, the model, and the original prototypes. Adding time, or duration, enables movement which transforms the static geometric description of a space into an immersive and interactive place that can be explored, and challenges us to think more deeply about how this place might be used. With virtually no fanfare, the first new ontological portal cracked open, allowing a trickle of phygital colonists to emerge, encounter and adapt to new media. We started to think differently about, and with, these newly constructed relational assemblages.

It was the recursive potential of open source that was really the key to opening the floodgates for colonization of the phygital nexus, and exposing the colonists to new ontological possibilities. Applying modern standard off-the-shelf technologies to the transcoded prototype allows 24-bit, high-resolution and interactive screen-based and virtually immersive immaterial recursions, each offering added apparent movement perception and sophisticated lighting arrangements to enrich the experience. In addition, the same open source code can output physical 3D fabricated instantiations which lend additional modalities of exteroception, such as tactile comprehension, on top of the already familiar scopic discourses.

Figure 35: Extending messy ontological assemblage

What becomes obvious is that even apparently simple encounters with an instantiation of the phygital Old Minster can never be neutral. They are always complex, mediated, intra-active events. When these instantiations are combined and augmented, as in our featured art/archaeology works, new insights into, and paradoxes within, our practices are added to our extending ontological assemblage as their relational agencies are purposefully articulated and entwined. For example, the conformation of the phygital Old Minster can endure in near perfection in the materialization and colonization recursions we have produced so far. However, that geometric stability is radically compromised when the phygital Old Minster is permeated with time and exposed to the entropic forces of dissipation and dematerialization. Lossyness, digital decay and phygital erosion are a few of the prime protagonists of dissipation we encountered, lurking in the nexus, during this collaboration. For example, every time an instantiation of the phygital Old Minster is compressed or (re)encoded for a new media format, details of the model are progressively, but haphazardly, lost in each successive recursion. Similarly, significant and intriguing differences emerge each time the phygital Old Minster is transformed when a physical instantiation breaks back into the virtual and then returns into the physical world (e.g. photogrammetrically recording a 3D print and then reprinting a new recursion by recapturing the 3D print through another computational photography intervention). After only one or two cycles, the initial sharply defined edges and vertices of the digital Old Minster seem to melt as its geometry collapses into itself. In exceptional circumstances, even the software model is not entirely immutable and certainly not guaranteed immortality. It too can dissipate if, for example, it is deliberately hacked to produce phygital fragments and form hoards. Of course, the model can also be obliterated if deleted.

However, these fragments, if not contained, will tend to disperse and gradually become more exposed to the force of dematerialization. Once activated, the effects of dematerialisation in the phygital nexus can range from coarse and emphatic to subtle, deceptively beguiling and beautiful. The former is exemplified by the polymer spoil heaps and scaffolding left by the 3D printing process. The latter are encountered in, for example, the ephemeral UV fragments produced as a byproduct of the photogrammetry, and the surreal images that are created as the ‘surface’ of the phygital Old Minster is totally dematerialized and transformed into a virtual RTI assemblage of strikingly-coloured surface normals. In our featured exhibits, different ontological instantiations (recursions and residues) of the phygital Old Minster have been brought, purposefully, into constellation to confront us with this multiplicity of being, and expose the ontological ambiguities obtained through the plethora of different techniques, transformations and tropes we rely on in the course of our art/archaeology practices.

In conclusion, appearances can be very deceptive. Emerging out of our continuing collaboration is an extending, messy, ontological assemblage. Within it, we include ontological mirages and algorithmic illusions, process-driven scale and shape shifters, chameleon-like skin changers, superficially simple material 3D prints, and ‘classic’ virtual animated tours; all recursions and residues. However, we have barely scratched its surface so far. This assemblage is not intended to, nor should it, be a static lasting comment on, or an inert record of, our collaboration with the (im)material entities with which we have begun to mix and mingle. Rather, it should be considered as an emerging, dynamic and intra-active conversation involving many actants, some yet to appear. The focus and meaning of this conversation is contingent on the shifting relationships of all actants which unfolds over time. These include our developing intentions as makers (both archaeologist and artist), refracted through our distinct and combined practices, the materials we work with, the application of highly trained modes of perception and expression, and our instruments of inquiry and presentation. All are agential participants and co-producers in this collaboration. In the case of the RTIs, the signatures of all the main actants and their intra-actions have been auto-archived interstitially as aesthetic paradata within this entangled art/archaeology ontological assemblage.

Acknowledgement

This visual essay is a contribution to a broader set of conversations being held as part of the COST Action (CA15201) ‘ARKWORK: Archaeological Practices and Knowledge Work in the Digital Environment[b]’[14]. PR represents the UK as an invited scholar.

References

Bailey, D. (2017) “Disarticulate—Repurpose—Disrupt: Art/Archaeology”, Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 27 (4), 691-701. DOI: 10.1017/S0959774317000713.

Barad, K. (2007) Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Duke University Press, London.

Beale, N, Beale, G, Dawson, I. and Minkin, L. (2013) “Making Digital: Visual Approaches to the Digital Humanities”, Journal of Digital Humanities, 2 (3). Available: http://journalofdigitalhumanities.org/2-3/making-digital-visual-approaches-to-the-digital-humanities/ (Accessed: 22.01.19).

Beale, G. and Reilly, P. (2017) “After Virtual Archaeology: Rethinking Archaeological Approaches to the Adoption of Digital Technology”, Internet Archaeology, 44. DOI: 10.11141/ia.44.1.

Beale, G., Schofield, J. and Austin, J. (2019) “The Archaeology of the Digital Periphery: Computer Mice and the Archaeology of the Early Digital Era”, Journal of Contemporary Archaeology, 5 (2), 154-73. DOI: 10.1558/jca.33422.

Bentkowska-Kafel, A., Baker, A. and Denard, H. (eds). (2012) Paradata and transparency in Virtual Heritage. Digital Research in the Arts and Humanities Series. Ashgate, Farnham.

Biddle, M. (2018) The Search for Winchester’s Anglo-Saxon Minsters. Winchester Excavations Committee Publication, Winchester.

Brown, D.H. (1995) “Contexts, Their Contents and Residuality”, in: Shepherd, E. (ed.), Interpreting Stratigraphy 5 - 1994 Norwich. ISBN 0952631407, 1-8. Available: https://www.york.ac.uk/archaeology/strat/pastpub/95ch1.pdf

Buchli, V. (2015) Archaeology of the Immaterial. Routledge, London.

Carter, M. (2017). “Getting to the Point: Making, Wayfaring, Loss and Memory as Meaning-making in Virtual Archaeology”, Virtual Archaeology Review, 8 (16). doi:10.4995/var.2017.6056.

Cornell, J. (Director). (1942) By Night with Torch and Spear. Available: https://vimeo.com/99334381 (Accessed 14.02.19).

Craig, B. (Ed.). (2008) Collage: Assembling Contemporary Art. Black Dog Publishing, London.

Cubitt, S. (2014) The Practice of Light: A Genealogy of Visual Technologies from Prints to Pixels. MIT Press, London.

Dawson, I. (in press) “Dirty RTI”, in Back Danielsson, I.M. and Jones, A.M. (eds.) Images in the Making. Art, process, archaeology. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Edgeworth, M. (2014) “From Spade-Work to Screen-Work: New Forms of Archaeological Discovery in Digital Space”, pp. 40-58 in Carusi, A., Hoel, A., Webmoor, T. and Woolgar, S. (eds.), Visualization in the Age of Computerization. Routledge, London.

Gant, S. and Reilly, P. (2017) “Different expressions of the same mode: a recent dialogue between archaeological and contemporary drawing practices”, Journal of Visual Art Practice, 17 (1), 100-120. DOI: 10.1080/14702029.2017.1384974.

Graham, S. (2018) 3d models from archival film/video footage. 20th January 2018. Available: https://electricarchaeology.ca/2018/01/20/3d-models-from-archival-film-video-footage/ (Accessed 060219).

Graham, S. (2019) Object Style Transfer, 4th February 2019. Available: https://electricarchaeology.ca/2019/02/04/object-style-transfer/ (Accessed 06.02.19).

Hamilakis, Y. and Jones. A.M. (2017) “Archaeology and Assemblage”, Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 27 (1), 77–84. DOI:10.1017/S0959774316000688.

Hofstadter, D. (1979) Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid. Basic Books, New York.

Horowitz, J. (1990) Maxell. http://jonathanhorowitz.us/video/maxell/.

Huggett, J. (2017) “The Apparatus of Digital Archaeology”, Internet Archaeology, 44. DOI: 10.11141/ia.44.7.

Jones, A.M. (2002) Archaeological Theory and Scientific Practice. CUP, Cambridge.

Jones, A.M. and Díaz-Guardamino, M, (2019) “Digital Collaborations”, pp, 211-213 In: Jones, A.M. and Díaz-Guardamino, M. (eds), Making a Mark: Image and Process in Neolithic Britain and Ireland. Oxbow Books, Oxford.

Jones, J. and Smith, N. (2017) “The Strange Case of Dame Mary May's tomb: The performative value of Reflectance Transformation Imaging and its use in deciphering the visual and biographical evidence of a late 17th-century portrait effigy”, Internet Archaeology, 44. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.44.9

Joyce, R. and Gillespie, S. (eds.). (2015) Things in Motion: Object Itineraries in Anthropological Practice. SAR Press, Santa Fe.

Latour, B. and Woolgar, S. (1986) Laboratory Life: The Construction of Scientific Facts, 2nd edition. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Kjølbye-Biddle, B. and Biddle, M., (forthcoming) The Anglo-Saxon Minsters of Winchester, Winchester Studies 4.i, OUP, Oxford.

Loyless, A. (2019). “Visualizing the York Minster as Papercraft” Epoiesen http://dx.doi.org/10.22215/epoiesen/2019.3

Lucas, G. (2012) Understanding the Archaeological Record. CUP, Cambridge.

Lucas, G. (2017) “Variations on a Theme: assemblage theory”, Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 27 (1): 187-90.

Minkin, L. (2016) “Out of our skins”, Journal of Visual Art Practice, 15 (2-3), 116-126. DOI: 10.1080/14702029.2016.1228820.

Moshenka, G. (2014) “The Archaeology of the (Flash) Memory”, in: Notes and News, Post-Medieval Archaeology, 48 (1), 255-59. DOI: 10.1.179/0079423614Z.00000000055.

Nissen, B. (2014) “Growing Artefacts Out of Making”, in: Proceedings of All Makers Now? Craft Values in 21st Century Production, Falmouth University. Available: https://makingdatathings.files.wordpress.com/2015/08/02-amn2014.pdf (Accessed 20 February 2018).

Perry, S. and Morgan, C. (2015) “Materializing Media Archaeologies: The MAD-P Hard Drive Excavation”, Journal of Contemporary Archaeology, 2 (1): 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1558/jca.v2i1.27083.

Petch, M. (2019) V&A Museum adds Scan the World to Cast Courts Permanent Collection, 3D Printing Industry, 24th January 2019. Available: https://3dprintingindustry.com/news/va-museum-adds-scan-the-world-to-cast-courts-permanent-collection-147822/. (Accessed 25.010.19).

Reilly, P. (1989) “Data visualization in archaeology”, IBM Systems Journal, 28 (4), 569–579.

Reilly, P. (1992) “Three-dimensional modelling and primary archaeological data”, pp. 145–173. in: Reilly, P. and Rahtz, S. (eds.), Archaeology in the Information Age: A global perspective. Routledge, London.

Reilly, P. (1996) “Access to Insights: stimulating archaeological visualisation in the 1990s”, in: Gedai, I. (Ed.), The Future of Our Past ‘93-‘95. Hungarian National Museum, Budapest.

Reilly, P., (2015a) “Palimpsests of Immaterial Assemblages Taken out of Context: Tracing Pompeians from the Void into the Digital”, Norwegian Archaeological Review, DOI: 10.1080/00293652.2015.1086812.

Reilly, P. (2015b) “Putting the materials back into virtual archaeology”, pp 12-23 in: Virtual Archaeology (Methods and Benefits). State Hermitage Publishers, Saint Petersburg.

Reilly, P. (2015c) “Additive Archaeology: An Alternative Framework for Recontextualising Archaeological Entities”, Open Archaeology, 1(1): 225–235. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1515/opar-2015-0013.

Reilly, P., Todd, S., Walter, A. (2016) “Rediscovering and modernising the digital Old Minster of Winchester”, Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, 3, 33–41. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17613/M66293.

Reinhard, A. (2019b) “Assemblage Theory: Recording the Archaeological Record”, Epoiesen, http://dx.doi.org/10.22215/epoiesen/2019.1.

Reinhard, A. (2019b) An archaeology of code: Quantitative analysis and context of Colossal Cave Adventure. Available: https://archaeogaming.com/2019/01/06/an-archaeology-of-code-qualitative-analysis-and-context-of-colossal-cave-adventure/ (Accessed 31.01.19).

Shane, J. (2018) Skyknit: When knitters teamed up with a Neural Net. Available: http://aiweirdness.com/post/173096796277/skyknit-when-knitters-teamed-up-with-a-neural (Accessed 30.01.19).

Stiegler, B., (n.d.) Ananmnesis and Hypomnesis. Available: http://arsindustrialis.org/anamnesis-and-hypomnesis (Accessed: 19.01.2019).

Sillman, A., Humphrey, D. and Green, E. (n.d.) team shag. Available: http://hamlettdobbins.com/curating/team-shag-collaborative-works-by-amy-sillman-david-humphrey-elliott-green/ (Accessed 14.02.19).

Stobiecka, M. (2019) “Digital Escapism: How Objects Become Deprived of Matter”, Journal of Contemporary Archaeology, 5 (2), 194-212. DOI: 10.1558/jca.34353.

Westwood, M. (2011) These Hands are Models. Available: http://www.stanleypickergallery.org/exhibitions/these-hands-are-models/.

Virilio, P. (2003) Unknown Quantity. Thames and Hudson, London.

Endnotes

1: Although it will not be explored at this stage, we recognise and embrace the potential to learn from the embodied practices of other maker communities in the phygital. For example, Bettina Nissen (2014) used small 3D sensors to track the gestures of crochet makers and 3D printed their creative movements. Elsewhere, another maker, Janelle Shane (2018), trained a neural net to create new knitting instructions, which members of the online knitting community Ravelry interpret in creative ways into physical creations.

2: Being (im)material is a grey zone where material and immaterial aspects of an entity coalesce. An example of an (im)material entity would be the combination of the immaterial code definition of an object and its 3D material printed output (Buchli 2015). See also Figure 27.

3: Refer to Cultural Heritage Imaging for an excellent up-to-date introduction to, and state of the art examples of, RTI practices (@chi): http://culturalheritageimaging.org/Technologies/RTI/

4: Recalling the work of film collage artist Joseph Cornell (1942).

5: To be distinguished from intentional metadata, that is the explicitly defined descriptions or attributes of the logged data (e.g., camera model, image size and format, date and time, specularity, diffuse gain parameters etc.) and the recorded reasoning and evidence embedded in the virtual anastylosis.

6: Increasingly, digital archaeologists are starting to explore the archaeology of code (e.g., Reinhard 2019b) and obsolete hardware and media platforms (e.g., Moshenka 2014; Perry and Morgan 2015; Beale, Schofield and Austin 2019).

7: A detailed account of the making of both the original and the new open digital models can be found in Reilly, Todd and Walter 2016.

8: See also https://www.southampton.ac.uk/tag2016/events/art-exhibition.page, https://www.academia.edu/28934530/Sightations_Café_session_Theoretical_Archaeology_group_TAG_Southampton_19-21_december_2016, and https://drpaulreilly.wordpress.com/2017/03/27/annihilation-event-digital-old-minster-the-archaeology-of-a-digital-file/

9: The TARDIS is a cult British TV Sci-Fi time and space craft that appears much bigger inside compared to its outward appearance and possesses innumerable rooms, corridors and spaces within.

10: http://www.iandawsonstudio.com/ian-dawson-along-the-riverrun.html

11: One portal into Groock’s Gallery is: https://robotgroock.wordpress.com/groocks-gallery-free-entry/