The Hunt for Bincknoll Chapel and the Public Archaeology Twitter Conference 3

Introduction

The theme of the third Public Archaeology Twitter Conference (‘PATC3’, 30/31 January 2019) was Archaeology as Storytelling, and I leapt at the opportunity to be involved. Within moments of reading the conference Call for Papers, I knew what I wanted to do: I would present a paper in the form of an archaeological comic, telling a story about a community excavation in Wiltshire (UK) that I was involved in during 2014/15. This Epoiesen article is my artist’s statement on that archaeological comic. The comic may be viewed on Twitter beginning at this tweet dated January 31st 2019.

Context

The 2018 Call for Papers said it all. "The very real excitement that can surround archaeology, for both archaeologists and members of the public, is often blurred or overwhelmed by the detail and time involved in... long and unwieldy reports, neglected archives and delayed or drawn-out projects. Creating a story out of your work can be challenging..."

My mind flew to archaeological artist, illustrator, and comic-maker John Swogger and his 2015 paper "Ceramics, Polity and Comics. Visually re-presenting formal archaeological publication." Published in Advances in Archaeological Practice, this paper embodies John’s challenge to archaeologists: that we must tackle the "visual wasteland" of archaeological publication by harnessing the unique story-telling powers of comics to communicate complex information. Furthermore, John’s effective adaptation of a peer-reviewed journal article from American Antiquity into comic format shows that it is possible to apply this visual structure, compositional language, and communication techniques, to formal, professional, presentation of archaeological data and interpretation.

This leads to the second part of the PATC3 Call for Papers. The conference aim was to explore "if a conference of archaeological stories, based on archaeological evidence, can both engage participants and transmit archaeological knowledge in a way that does not dilute the science and rigour behind the narrative." Could I do this in a comic, as John’s demonstration suggests is possible, but also within the conference constraint of no more than 12 tweets?

Concept

I wrote my abstract, 175 words of traditional proposal for a paper titled "The Lost Chapel of Bincknoll". It illustrates where my mind’s eye was in 2018:

The Lost Chapel of Bincknoll

This paper is a re-visioning of two excavation reports published in 2015 and 2016 in a county archaeology journal: inspired by John Swogger’s transformation of a peer-reviewed paper in American Antiquity into a comic that brings text and image into closer relationship, and using comics’ design elements to foreground sequence and narrative.

The reports describe and interpret the investigation over two excavation seasons of the remains of a small medieval building in north Wiltshire. The fieldwork was a collaborative community project between Broad Town Archaeology and the Wiltshire Archaeology Field Group. It also involved members of the Young Archaeologists’ Club. The two published papers are traditional, formal, excavation reports, full of interest and illustrated by accompanying images.

I now re-present the excavation results in comic form, taking advantage of the form of a tweet (analogous to a comic panel, in which image and text can be integrated) and Twitter’s threading functionality (analogous to the sequence of panels in a comic) to tell the story of the lost chapel of Bincknoll.

#BincknollChapel #PATC3

That twin affordance of Twitter referred to in the abstract’s last paragraph, to combine image and text in an immediate, small, enclosed, easily-read space (i.e. a tweet), and to story-tell through a thread (of linked tweets), was the burning lightbulb at the heart of my idea. But I intended not simply to make a comic comprised of panel drawings shared via the maximum number of images that I could display in 12 tweets (48, assuming four images posted per tweet). My original concept relied on Twitter’s intimate relationship between tweeted text and a tweet’s image.

When I access Twitter via my laptop, and click on an image posted in a tweet, something great happens. The image opens and is fully-revealed, and the text of the tweet appears in a ribbon over the bottom edge of the image. A comic panel is formed.

As John writes, "Our world is shaped by media which do not separate or segregate image and text, but bring them together." Twitter is set up to integrate image and text in this way. A dynamic relationship is created between the image and text, through both the physical movements that I have made operating my laptop and also the programming that causes the tweet text to move from above the image, as it appears in a Twitter user’s timeline, onto the image itself.

My original concept intended to take advantage of this by posting twelve images with twelve ‘captions’. When delegates participating in PATC3 would click on the image in one of my conference paper’s tweets, they would activate this functionality that places the tweet text over the opened image. This was not intended to be simply another comic posted on Twitter: it was meant to be a Twitter comic.

Tweet 2/12

Making

The 2014/15 excavations at Bincknoll, a hamlet in rural north Wiltshire (UK), were published in two papers in the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine (Clarke and Sanigar, 2015; Clarke and Elton, 2016). In the first digging season, I and a volunteer team of adult leaders had taken a small group of Young Archaeologists’ Club members on a day visit to the site. During the second season we were on site for a whole week, responsible for excavating and recording one of the trenches over the building remains that were being uncovered. I began my conference preparations by re-reading the two reports, remembering my experiences on site, and calling on the principal site director, Bob Clarke, for additional photographs.

Allowing for tweet 1/12 to be the comic title page, and tweet 12/12 for the credits, enabled me to budget ten tweets to tell the story of the excavation and its main conclusion: that the building foundations we had uncovered in the front garden of a small cottage were the remains of a medieval chapel. This I story-boarded, deciding which were the key archaeological details that must be included to substantiate the published interpretation of the site. This was an important consideration, bearing in mind the conference Call for Papers requirement to "transmit archaeological knowledge in a way that does not dilute the science and rigour behind the narrative".

It was then a simple matter to draw up the first draft of the twelve panels, decide which worked and which did not, and make changes to the less effective panels. These changes included abandoning an idea to illustrate the title page with portraits of the key site staff; and sticking to less human-scale, but simpler, overhead views of work on site and site plans, rather than drawing oblique images that would have been more like the view experienced by a visitor in person.

I regret losing the portraiture: but the community excavation was very collaborative and included so many significant people that it was difficult for me to compose into a legible image the dozen-or-so ‘head-shots’ required around the comic title. Also, I just wasn’t skilled enough to draw believable caricatures beyond the three or four people I knew best. This personal touch was thus absent. The friendly and caring landowners, the morning and afternoon tea-breaks with home-made cake, the accommodating and supportive archaeologists: these relationships that made the project are missing from the comic. Relying on overhead views (tweets 3/12, 5/12, 7/12, 9/12, 10/12) was less troublesome to me, and a pragmatic decision to do with time. I couldn’t find a photograph to given me precisely the angle on site that I wanted, and there wasn’t enough time for me to sketch and re-sketch a panel to get this right without recourse to a shot from the site photo record. Again, skills (or, lack thereof).

For visual and structural uniformity across the twelve tweets, I cut out a cardboard template to define each panel border. The rectangular, landscape-oriented template had rounded corners to mirror the format of images in a Twitter timeline. That gave me a thick black line to delimit each panel. When you click on a tweeted image, however, it opens and those rounded corners are lost as the whole image is revealed. This meant that I needed to include a white border around each panel frame; conveniently providing me with additional visually-helpful white space on screen.

I draw my comics up on layout paper first. Layout paper is lightweight and semi-transparent, for the artist to cut bits up and move around a design, trace from, and generally get their work in order. With twelve panels marked out using the cardboard template, I drew the story.

Tweet 1/12

The revised title page (tweet 1/12) now included a scene-setting image, placing the title The Hunt for Bincknoll Chapel at the foot of the wooded hill on which stands the earthwork remains of Bincknoll Castle. This establishes both spatial and temporal context: the excavation was at the foot of the hill, and the story is set in the present day as we investigate archaeological evidence together. The conclusion (tweet 11/12) replicated this scene, but now placing us in the past: the castle on the hill is reconstructed and the chapel can be seen below, with a quote from the excavation report giving us the headline finding – that the dig had found the remains of Bincknoll’s manorial chapel.

Tweet 11/12

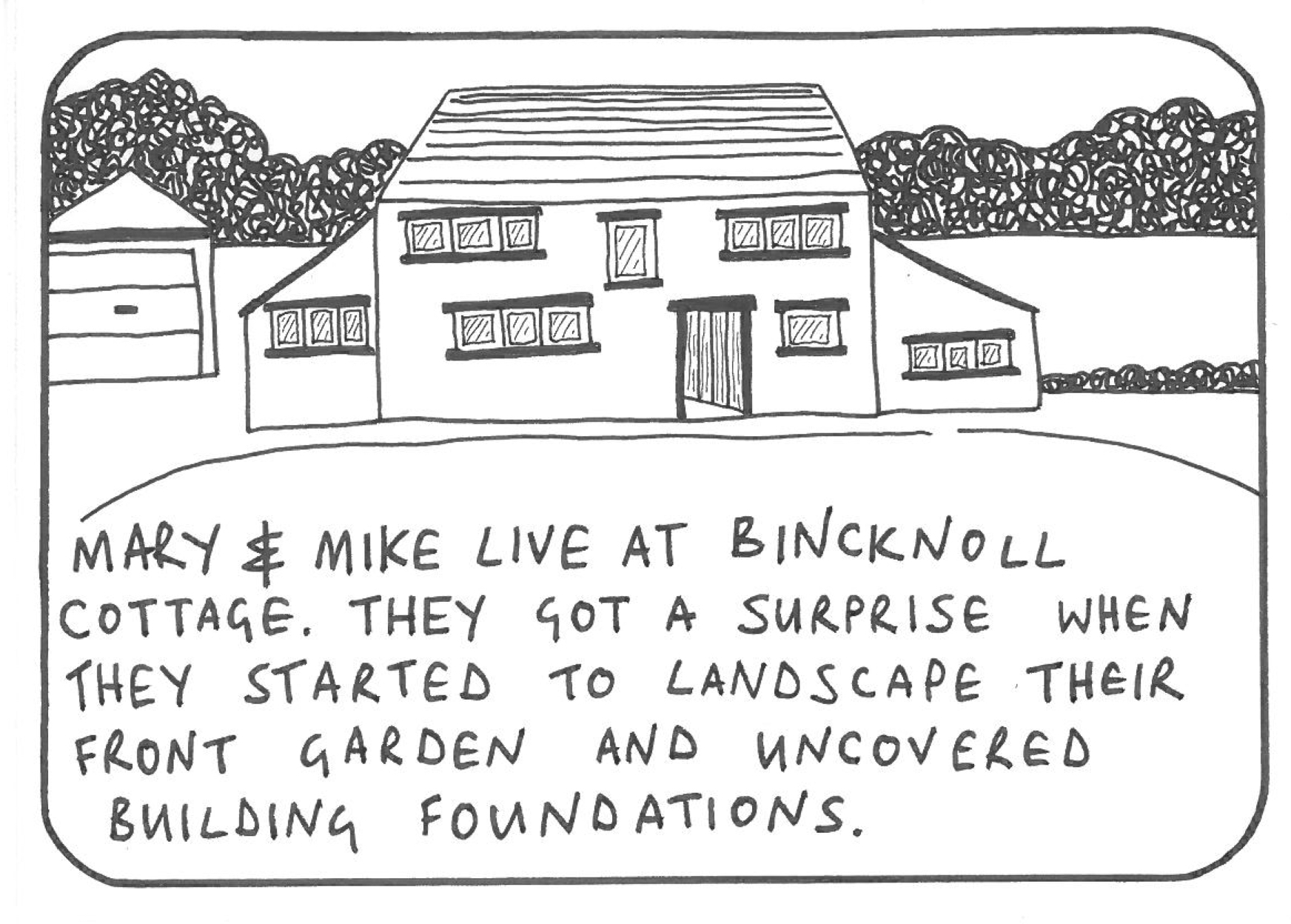

Three tweets (2/12 to 4/12) provide the cultural resource management context. Unexpectedly, archaeological remains had been uncovered in a domestic setting; the County Archaeologist was involved; and community groups comprised of a mixed membership undertook the excavation. Now that so few people would appear in the comic, it was important to me to establish the human and personal genesis and conduct of the project as best I could. Using only the landowners’ first names, for example, is both personalising and, in part, a security choice (although anyone can, through the published reports, fully identify them to invade their privacy if so minded).

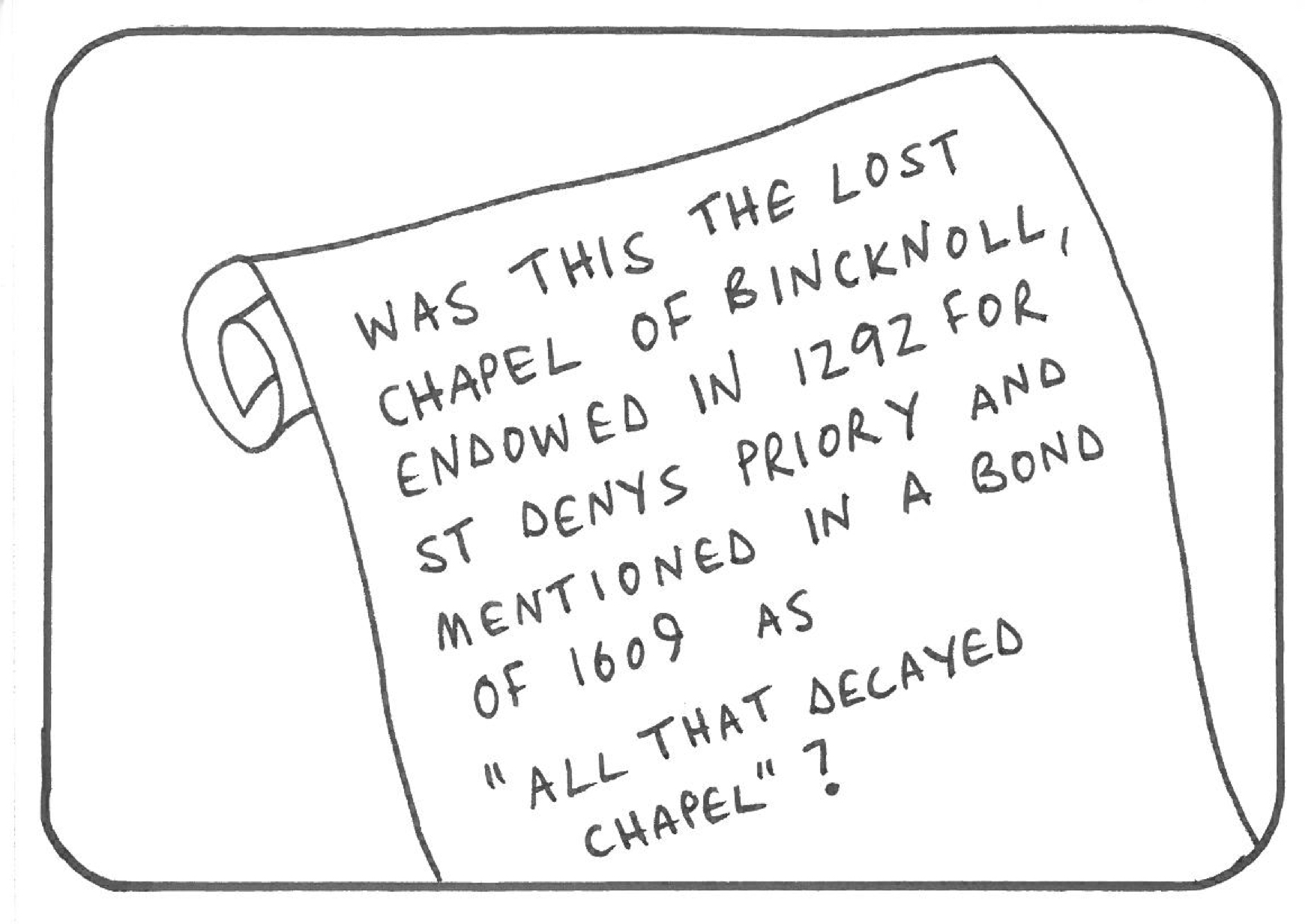

The key archaeological findings underpinning the site interpretation are the building plan, size, and orientation, and the artefacts recovered from contexts within the footprint delimited by the foundations. Additionally, historical research identified the few records of a long-lost ecclesiastical building at Bincknoll. Tweets 5/12 to 10/12 provide this information that underpins the excavators’ conclusions. Rather than mimicking the excavation reports’ structure, in which individual trenches are described and separate finds reports are made, the comic is structured chronologically. It reflects the discovery and ongoing questioning and answering – the hermeneutic cycle of the project – in my attempt to recover some of that "very real excitement that can surround archaeology" and "both engage participants and transmit archaeological knowledge" mentioned in PATC3 call for papers.

With re-draws of two of the panels easily completed on layout paper and pasted over their failed originals, I could then trace off the twelve panels ready for scanning.

In the meantime, I had realised that my original concept, the ‘Twitter comic’ in which panels comprise an image overlain by text derived from the tweet, would not work. I had been tinkering with Twitter on different devices. I’m lucky to have a smart phone, a tablet, and a laptop. With my comic in mind, I had been paying more attention to how images work on the social media platform. It was only on my laptop that tweeted text displayed in a ribbon at the bottom of an opened image. On my phone and tablet, an opened image was accompanied by only the ‘reply’, ‘retweet’, ‘like’, and ‘tweet activity’ symbols. What devices would the conference delegates be using to participate and view papers? I couldn’t draw only the images, leaving a space for the planned tweet text to fall into: each panel would have to include any required text. This is why tweets 2/12 to 11/12 include my hand-written caption. Although there is a visual consistency throughout – except tweet 8/12 where I was able to bring in the idea of historical documentary evidence by marrying text with a scroll form – this immediately set up accessibility problems, and of course removed the original concept at a stroke.

Tweet 8/12

Reflection

On the whole the conference paper seemed to be well-received with plenty of likes and re-tweets of individual panels and even some compliments: by some of my existing followers but also conference delegates, other archaeologists and archaeological illustrators, and a few people who, if their Twitter profiles are anything to go by, don’t identify with heritage in any explicit way. Mostly, I got what I wanted from the experience: a test of my skills to condense the technical excavation reports into a more engaging and definitely briefer narrative; and some conference conversation about comics and, in archaeological illustration more widely, issues around interpretive uncertainty, and technical and illustrative style, and how the artist makes choices about what to depict in an image, and how to depict it.

In terms of wider engagement, the PDF version of the paper that I posted to the Humanities Commons CORE has been downloaded 63 times (as of 16 August 2019). To my great surprise, however, the paper later became one of the discussion points in Matthew Edwards’ ’zine A Reflection on the Third Public Archaeology Twitter Conference. The 'zine is Matthew's final submission for a seminar directed by Dr Shawn Graham at Carleton University, Ottawa (Canada): he chose to analyse and interpret data about PATC3 to explore to what extent the conference met its aims, and what issues there are around this form of public engagement. Matthew pointed out things about my paper, that I had not fully appreciated myself, such as the way that my retention of archaeological conventions of the aerial photograph, site plan, and interpretative plan created an "archaeological mood" which "encourages her audience to connect her narrative to previous experience with archaeology". Hopefully, those conventions lent some gravitas or rigour to my simple black and white line style and condensed account of the excavation.

On the other hand, did I take too much for granted the readers’ knowledge of archaeological practice? Laurel Rowe points out in these pages that the reader of a comic must fill the gaps between each panel, imagining the missing action on the basis of the intimations made visually by the artist. How much does reading my comic rely on having an awareness of archaeological processes, likely sequences of work and action on site? As Laurel mentions, the chronological structure is an affordance of the comic medium. As events unfolded for the archaeologists and the archaeology, so the story unfolds for the reader scrolling from tweet to tweet, looking from panel to panel. Is the ‘reveal’ of the next tweet like the turn of the printed page, or of the trowel in the earth? Mediated by Twitter, the comic struggles to use many of the visual compositional strengths that are possible on the page such as breaking across the gutter.

The principal failure of the paper was in not being what I have been calling a Twitter comic. I could not deliver my original concept, because different devices display tweeted images and their tweet text differently. This then set up a series of accessibility issues for me, which I did not deal with adequately. With captions hand-written into each panel, I could no longer rely on functionality like screen-readers to deliver the words to participants. To my shame, I hadn’t allowed time to deal with this: I hadn’t prepared Alt Text for each posted image, and I didn’t use a running commentary tweet-to-tweet either, to repeat the panel text. I have remedied this in a small way in the online PDF at Humanities Commons, by including Alt Text and checking the resulting file for its accessibility score.

There are a few small errors in the drawings. For example, in my haste, I mis-understood an aspect of the interpretation of the eastern end of the building which has an impact on the interpretative plan in tweet 10/12. Although I had asked the principal site director, Bob Clarke, for his permission to adapt the two site reports, I didn’t approach the Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society (of which I am a member) in advance. That would have been polite, at the very least. If I was doing this over, I would allocate more time to discussing the idea with stakeholders and preparing the comic panels to be as accessible as I could make them.

It’s a shame that I can’t link from the comic to the full published reports, because the county archaeology journal is produced only in analogue format. Next time, I’d want to make the comic a little less like an excavation report by including more human-scale images, oblique views, and the people involved in making the project the enjoyable experience that it was for all ages. Apart from my voice, the voice of the excavation report authors dominate this comic. What would the voices of the chapel builders and worshippers look like?

Twelve tweets for a conference paper of this nature enabled me to deliver a very limited interpretation of the excavation and site. There were other finds that I didn’t draw (like lead window cames), other archaeological activities that I didn’t depict (like photography and other recording methods), many other people are missing. But then maybe this short and engaging version of the story is all that most readers need? After all, who is going to read this comic? I don’t think any more than two or three of the other people involved in the project on the ground will see it, and they have their own memories and value to take from the experience. For everyone else in the Twitterverse, maybe my little comic is all that they need to find out what happened when we went on the hunt for Bincknoll Chapel.

Works Cited

Clarke, B. and Sanigar, J. (2015) The Lost Chapel of Bincknoll, Broad Town, north Wiltshire: an interim report on excavations at Binckoll Cottage 2014 Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society Magazine 108, 133-142

Clarke, B. and Elton, E. (2016) The Lost Chapel of Binckoll, Broad Town, north Wiltshire: final report on excavations at Bincknoll Cottage 2015 Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Society Magazine 109, 126-142

Rowe, Laurel. 2018. “Contains Scenes of a Graphic Nature: Sympathy for the Devil”. Epoiesen. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22215/epoiesen/2018.5

Swogger, J.G. (2015) Ceramics, Polity, and Comics: Visually Re-Presenting Formal Archaeological Publication Advances in Archaeological Practice 3(1), 16-28 (https://doi.org/10.7183/2326-3768.3.1.16)

Cover Image Courtesy Katy Whitaker Tweet https://twitter.com/artefactual_KW/status/1090916466587824128

Masthead Image Courtesy Katy Whitaker Tweet https://twitter.com/artefactual_KW/status/1090920033797197824