Visualizing the York Minster as Papercraft: First Response

Lemonade stands are for suckers. When I was a kid, I wanted to sell papercrafts. Nothing fancy; my biggest production was paper snowflakes. I got pretty good, cutting out relatively complex designs and shapes with my chunky pink scissors. I cut so many that it became like a science to me: I knew that if I cut here, the final shape would show up there. I would imagine and execute patterns of stars, pine trees, hearts, even Santa’s silhouette with confidence and ease. But no matter how many I made, the magic of the final moment - unfolding the snowflake to see it in its full beauty - remained powerful. Holding up snowflake after snowflake to the light, I felt that they twinkled just like those that landed on my mittens in the winter (yes, my paper snowflake business venture was a summer activity). Though they were made of ordinary paper, to me, they were brilliant.

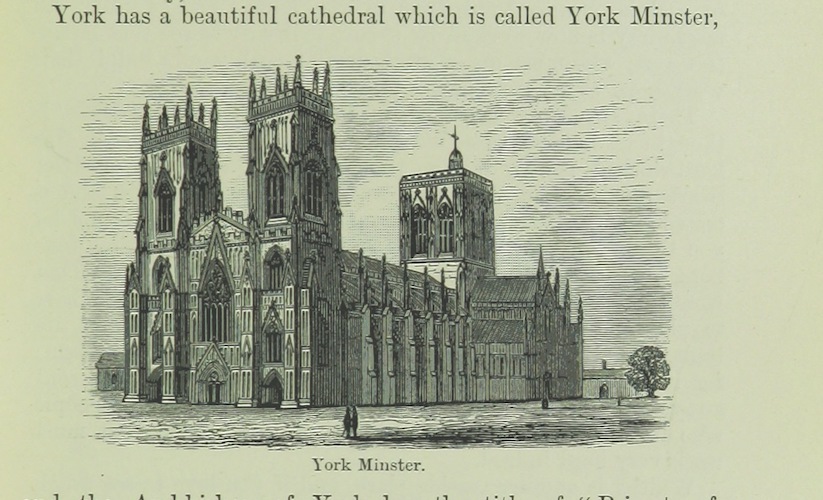

As I scrolled down and saw the blue images of the York Minster papercraft draft, I thought of those moments unfolding the snowflakes. I’ve never seen York Minster in person. The Google Earth image in the article was the first time I laid eyes on it, actually. I can imagine it, though, having seen my fair share of churches, cathedrals, and other significant Gothic heritage buildings. I think of other moments that took my breath away: looking up at the cathedrals in Siena, Milano, and Paris, or Westminster Abbey. Maybe a little more spectacular than my paper snowflakes.

But paper can be magical. I look at the actual image of York Minster from Google Earth and, truthfully, I feel nothing. The first pulse of excitement comes when I open the Illustrator files. Clean and simple, these outlines come from something so complex and intricate. I don’t have a printer, but I imagine the patience it would take to slice out each small individual shape, each detail that makes this building unique. Not to mention the patience it took to create these Illustrator files in the first place. I imagine myself trying to cut out the windows of York Minster with my childhood pink scissors. Impossible. I think how it’s pretty neat that I could try it if I really wanted to, just to see how it would turn out. I ask myself: how many computers is this existing on right now? How many changes have been made without me knowing? How many experiments, botched trials and errors; how many fairy lights have lit York Minster, maybe in red, green, or multi-colours?

In its supposed simplicity of printer paper and fairy lights, of tape and glue, this York Minster can be built by my own two hands. I could feel every curve and sharp edge. I could trace the point where each wall meets. In its supposed simplicity, heritage papercraft makes this all tangible. It can push us beyond those moments, standing awe-struck below a towering building. Because if a little paper model makes me whisper “wow,” then maybe the enchantment of York Minster, and Notre-Dame, and il Duomo di Milano, doesn’t necessarily lie only in the physical structures themselves.

There’s so much that can be said about heritage papercraft; about making the tools accessible and interactive; about creating and recreating heritage buildings in our own homes, and what this all means for history and archaeology. As Sara Perry states in “The Enchantment of the Archaeological Record”: “We are literally atop untold histories: things, ideas, lives, and activities that we have never seen before, that we may know nothing of, and that can thus endlessly surprise and transform us” (355). Yet papercraft is something we do know, and that bond formed between something familiar and nostalgic and something unknown and untold, that’s enchanting.

Touching, building, shaping through papercraft not only allows us to experience built heritage in a different kind of physical way: it’s a performative practice. And all performances are unique. There’s the image of a young Cassandra, sitting cross-legged on her bedroom floor, flourishing her chunky scissors as the wooden basket beside her fills with construction paper snowflakes. There’s the performance of someone hunched over a cutting mat, a thin, silver X-Acto knife in hand, making one small cut and removing one small piece at a time. Stu Eve’s “Augmenting a Roman Fort,” taking the existing Make This Roman Fort (Usborne Cut-Out Models), and adapting it through an augmented reality app, is an example of another kind of performance: one that exists both in the “real” and virtual worlds. The York Minster project is open to this kind of intervention as well, keeping the construction blank and available for a variety of virtual and physical adaptations depending on the builder. In both the Roman fort and the York Minster, builders are meant to navigate between instructions and intuition, bringing their own agency to histories past; bringing these histories past into the present. Everything in between and beyond adds another layer of performing the construction and history of built heritage through papercraft. Not only to understand that construction and history, but to expand it.

How do our relationships to built heritage change through papercraft? How does that moment of enchantment - turning on the fairy lights so that our model York Minster glows blue from the inside - reshape our experiences with built heritage? I think it offers the opportunity for us to make diverse and meaningful connections, not just to the building’s past but to the moments that our pasts have intertwined with it. To look at built heritage, then, is not passive, but becomes an active process of understanding on a deeper, more personal level, how our histories are physically and emotionally linked to the past.

To look at built heritage and remember your pink scissors; to see the model York Minster and remember your woven basket of snowflakes on your bedroom floor; that’s special. And so, I have snowflakes on my mind. The only way to shake it is to make one right now.

Paper snowflake inspired by "Visualizing the York Minster As Papercraft"

Works Cited

Eve, Stu. 2011. Augmenting A Roman Fort. Dead Men's Eyes Oct 20. https://www.dead-mens-eyes.org/augmenting-a-roman-fort/

Perry, Sara. 2019 The Enchantment of the Archaeological Record. European Journal of Archaeology 22(3), 354-371.

Cover Image "Image taken from page 214 of 'Allgemeine Erdkunde ... Bearbeitet von Dr. J. Hann, Dr. F. v. Hochstetter und Dr. A. Pokorny ... Zweite vermehrte und verbesserte Auflage'" British Library Flickr

Masthead Image "Bulley, Eleanor. 'Great Britain for Little Britons. A book for children' p45."British Library Flickr