Editorial Note: Everything is Phygital

Volume 3

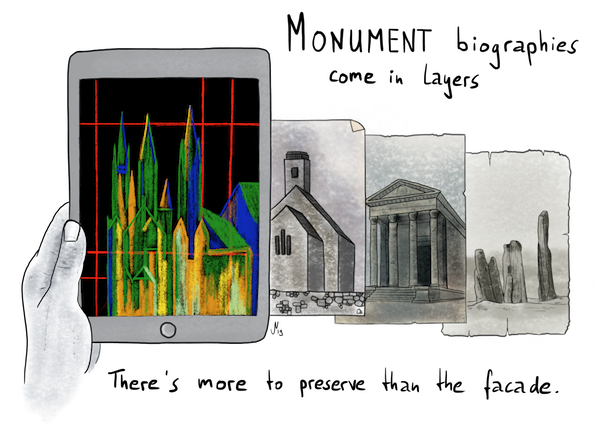

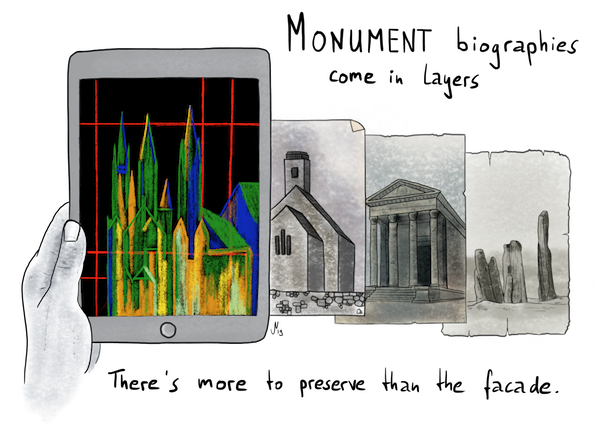

The cover of this year's print edition of Epoiesen (volume 3) features artwork by archaeologist Jens Notroff. Jens is also an illustrator and science communicator, and his work never fails to delight, challenge, and confound. His piece, ‘Monument Biographies Come in Layers’ reminds us that there’s more to preserve than the facade. I take this as a call to remember the intangible aspects of not just culture or heritage, but of the digital work through which more and more we are coming to know the past.

'Monument Biographies Come in Layers,' Jens Notroff, CC-BY-SA

As I look at the work, I imagine a single site, a place of power in the landscape, evolving as the networks of power and ideology and imagination reconfigure around it over time, until it becomes ‘phygital’ in the sense that Dawson and Reilly discuss:

A phygital nexus can be thought of as a no-place and an every-place where digital and physical worlds intersect; a space where novel, ‘messy assemblages’ can emerge

... they tell us. I’d like to think that that’s what’s happening here on Epoiesen this past year: a glorious space of messy assemblages of ideas, media, and making. Opitz calls this idea of the 'phygital' a ‘modern transubstantiation’ and provocatively asks, ‘...and so what if it is?’ The answer, she says, is that it gives us license within our framework of rational science to connect and engage the mystical, the spiritual, or at the very least, the ‘more-than-physical’.

It makes me wonder if perhaps there is a connection here with the work of the practitioners collected in the new volume on 'Historic Landscapes and Mental Well-Being', edited by Timothy Darvill, Kerry Barrass, Laura Drysdale, Vanessa Heaslip and Yvette Staelens. Darvill writes, in the Introduction to that volume, that well-being

does not involve a single universal ‘right’ balance of these things [eg hope, charity, justice, creativity, etc] because the balance varies from person to person. As such, well-being is not so much about wellness per se as about a heightened sense of ‘being’, and an awareness of the continual process of ‘becoming’. (Darvill et al, 2019, p5)

That 'heightened sense of 'being'' I think is consonant with what Sara Perry has argued for in the sense of archaeological enchantment, drawing on the work of Bennet, 2001. 'Disenchantment' is not a rationale, clear-eyed view of the world; rather it is a blinkered shutting-off-of-possibilities. Thus enchantment is not about magical thinking but rather about opening to the sources of wonder in the day-to-day we encounter, and these encounters become what Perry calls 'seedbeds' for ethics of generosity and care.

It seems to me, and through no conscious planning on our part, that this past year of Epoiesen has been about pieces that sit at this intersection of the physical and digital world, that enchant us, and in that enchantment perhaps reminds us of the potential of archaeology and history to promote care, generosity, and well-being. The pieces that we put online in 2019 all connect with the ‘vibrant materiality’ (Bennett, 2010) of the past, the vibrating chords that intersect and tie us to the past in the visions of the past that we create. It is an enchantment of the kind that Fredengren (2016) describes in her work on Irish Crannogs, the eruption of deep time into new and novel forms that stop and arrest us. Reinhard’s work with found digital sounds and the act of assembling music from them takes the idea of ‘vibrant’ in an altogether new direction. Caraher and Smith’s reaction to the piece, and the consideration of how the piece is affected by the materiality of their ability to listen, causes us to stop, pause, and realize that many of the assemblages (all?) that we deal with in archaeology only exist through other media. That their meaning is transformed.

It’s all heady stuff. Morely, Dal Borgo, and Fragoulaki take us through playful engagement with a serious (and always politically relevant) Melian Dialogue, while Whittaker engages us in a visual dialogue about a single point in space that is encountered through the medium of the Twitter Conference. Loyless and Marsillo enchant us with papercraft (delivered digitally) and the ways memory and knowing are embodied in touch.

In which case, it seems that in 2019, everything is phygital.

References

Bennett, J. 2001. The Enchantment of Modern Life: Attachments, Crossings, and Ethics. Princeton (NJ): Princeton University Press.

Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham: Duke University Press.

Darvill, Tim, Kerry Barrass, Laura Drysdale, Vanessa Heaslip and Yvette Staelens (eds). 2019. Historic Landscapes and Mental Well-being. Oxford: Archaeopress.

Fredengren, C. 2016. Unexpected Encounters with Deep Time Enchantment: Bog Bodies, Crannogs and ‘Otherworldly’ Sites. World Archaeology, 48: 482–99

Perry, S. (2019). The Enchantment of the Archaeological Record. European Journal of Archaeology, 22:3, 354-371. doi:10.1017/eaa.2019.24