Classicist in Disguise

Editorial note: in some browsers, 'autoplay' might be turned off by default for the looping videos below. If you see a grey square, right click and select 'show controls' then 'play'. On mobile devices, this piece is best viewed in landscape orientation.

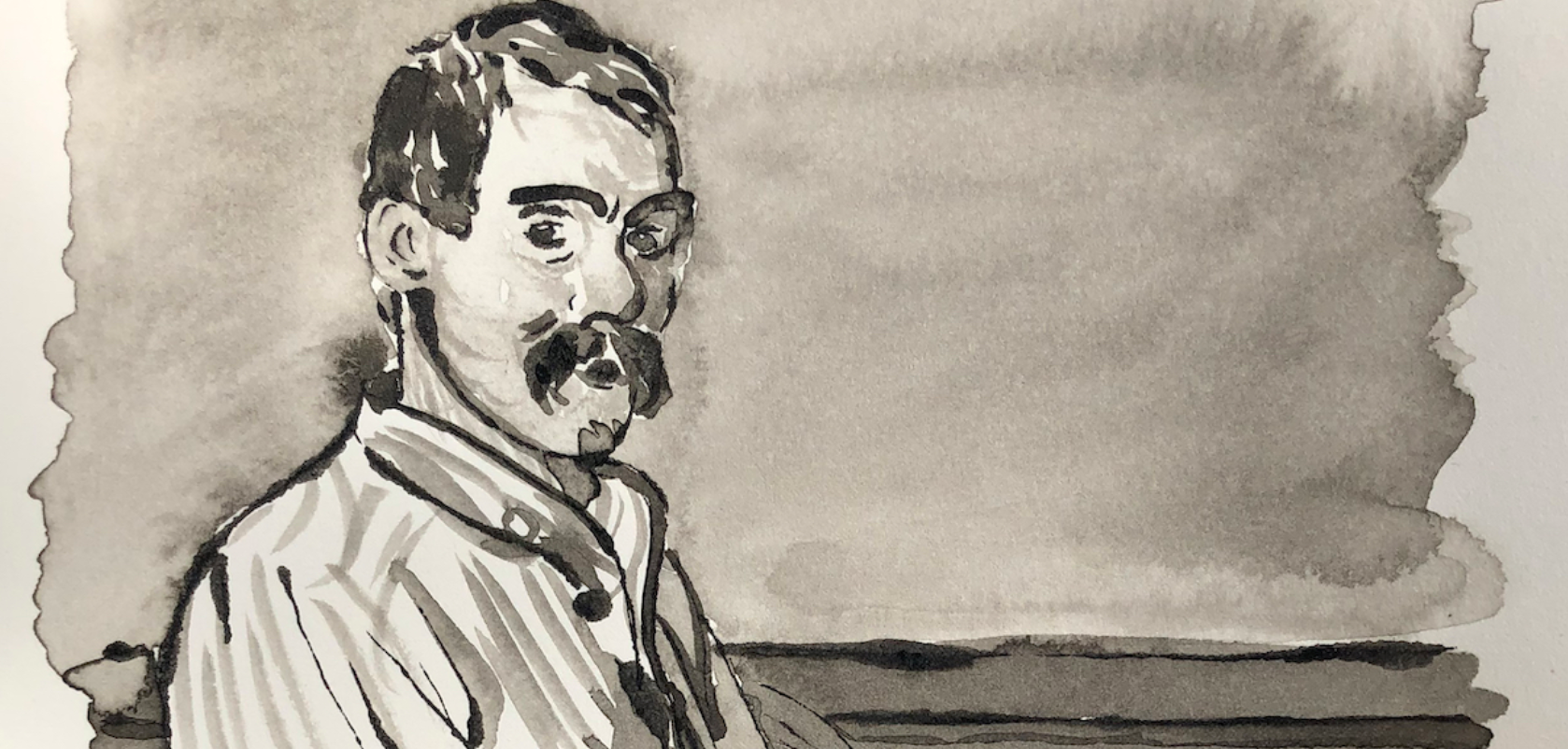

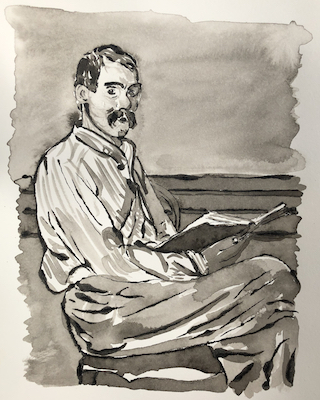

Burton had prepared to be Abdullah for years. He changed his language, his facial expressions, the way he walked and ate and slept. Since even a glass of water could expose him, he had to remember to praise Allah before and after drinking, gulp rather than sip, and clutch the tumbler "as though it were the throat of a foe." He had himself circumcised so that his body would not wordlessly reveal him.

For the rest of his life, Burton signed letters to friends "Haji Abdullah" – Abdullah who has completed the Hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca. The book he wrote when he returned, Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to Al-Madinah and Meccah, is the story of the birth of the Haji, the uneasy, twinned merging of Burton and Abdullah.

I first read the Personal Narrative during my first weeks at college, as I formulated a disguise of my own. I grew up in Tucson, Arizona, in an Evangelical Christian family. I was also sent to a private Evangelical school, where the teachers were chosen for the strength of their faith rather than their knowledge. We learned about the past so the teachers could warn us about the demons who controlled the ancient Egyptians, and might tempt us away from Christianity, too. I was intrigued by the images of the ancient world. I came to New York to study them from people who wouldn’t also tell me about sin.

I spent eleven years at Columbia, completing my undergraduate degree and then a Ph.D. in ancient art history. I learned five languages along with libraries-worth of arcane knowledge. I learned how to drink prosecco at a reception alongside an Egyptian temple, rummage through museum storerooms, and eat asparagus at the high table at a Cambridge college. Yet I always feared that I would make some slip and be unmasked as the imposter I thought I was.

My life was lived at a remove. I checked each impulse against the rules I had ascertained for each situation. I learned what to drink (red wine) and how much (two glasses). I learned that the "goat" in "goat cheese" is a factual descriptor of origin rather than, as I had believed, some sort of playful metaphor. I learned I shouldn’t wear my hair in braids when a fellow graduate student informed me he had heard a rumor that I was Amish. Like Burton training himself to be Abdullah, I changed what I wore, what I watched and read, what I knew, and what I said. I changed whom and why I loved. It worked. After a few years, if I admitted that I grew up in Tucson, people’s foreheads would wrinkle in confusion.

In the Personal Narrative, the Haji explains that he did not want to be seem as a "new" Muslim, "to be pointed at and shunned and catechised, an object of suspicion to the many and of contempt to all." And so, the Haji chose to disguise himself as someone who had been a Muslim for his whole life.

The Haji would spend five months in disguise, steaming to Cairo, sailing in a ship crammed with pilgrims on the Red Sea, and then on camel-back through the desert in a caravan to the holy cities. He had dark hair and eyes, but looking the part wasn’t good enough. He knew fellow pilgrims would "while away the tedium of the road by asking questions," like the man on board the steamer to Cairo who attacked him with a "hot fire of kind inquiries," or the persistent camel-tenders in the caravan who, "are never satisfied till they know as much of you as you do of yourself." So he fabricated a history for himself, one whose mixture of influences and geographies would excuse any gaps in his knowledge, eccentricities in behavior, or mistakes in vocabulary or accent. He described himself as having been born in India of Afghan parents, educated in Burma, and then "sent out to wander." The structure of his pretended childhood mirrored the reality of his own peripatetic youth. His parents were English, but he was raised mostly in France and Italy. After less than a year at Oxford, he went to India to serve in the army. The Haji was an Englishman who was rarely in England.

He made his disguise more plausible by layering on other disguises. At times he pretended to be a resident of Medina, to avoid a pilgrimage tax on foreigners, and he convinced his camel-tenders that he was Turkish. He also called himself a religious wanderer under a vow to visit all Islamic holy places, after a man he met in Cairo recommended that this would persuade people "that you are a man of rank under a cloud, and you will receive much more civility than perhaps you deserve." To penetrate one of his disguises was merely to drop through into the next.

The Haji published his translation in 1885 – privately, to subscribers only, because by a "plain and literal translation" he meant that he had left in the sex. In fact, he added quite a bit more, with footnotes and essays about the sexual mores he had observed during his travels in Arabic-speaking countries. He was in his early sixties when finishing the translation, and his commentary spools out the observations of a sharp-eyed life.

The Haji was brilliant, funny, sexy. He was the type of person I had come to New York to meet. The fact that he had been dead for more than a hundred years was a relief. It meant he wouldn’t expect anything of me. But he could be my role model for how to take a hostile culture by surprise.

The Haji wrote that, when he at last saw the Kaaba, the granite shrine covered by a black curtain which is the holiest site of Islam,

of all the worshippers who clung weeping to the curtain, or who pressed their beating hearts to the stone, none felt for the moment a deeper emotion than did the Haji from the far-north…. But, to confess humbling truth, theirs was the high feeling of religious enthusiasm, mine was the ecstasy of gratified pride.

The Haji felt ecstasy as he penetrated the mysteries of Islam, but he also thought that his emotion was humbling and low in comparison to the "high feeling" of the other worshippers. He got what he thought he wanted, but he wasn’t satisfied with it.

Eight years after I earned my Ph.D., I reached the goal I had set for myself: tenure. Like the Haji, I had worn my disguise well enough to reach my destination. I began to think about the right of academic freedom that I had supposedly won. I could think anything, write anything. But once the ecstasy of gratified pride subsided, I felt hollow, as if my disguise was wrapped around a vanished center.

The Haji, too, seemed unable to say exactly who he was after his pilgrimage. Sometimes he would declare he was indeed a Muslim, and other times deny ever even considering converting to Islam. He wore a leather pouch he wore strung around his neck as he travelled the world, first as an explorer and then serving the Foreign Office as counsel in Africa, Brazil, Damascus, and Italy. When he met Muslims, he opened this pouch and pulled out a certificate signed by the Sheikh of Mecca to prove he had made his pilgrimage. But the pouch around his neck also held a letter from Cardinal Wiseman commending him as a good Catholic. Yet, his devotedly Catholic wife tried all her life to convert him, and succeeded (she thought) only on his deathbed, when he failed to object verbally to a priest administering baptism and last rites both together.

For the rest of his life, some combination of his appearance and his fame made other Europeans continue to think that he looked like an Arab. The poet Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, who met him in 1868 in Buenos Aires, noted that the Haji had "a countenance the most hideous I have ever seen, dark, cruel, treacherous, with eyes like a wild beast’s. He reminded me of a black leopard, caged but unforgiving."

In each of his diplomatic posts, the Haji was dogged by accusations that he did not defend English interests enough, because he was too sympathetic to foreigners. He was caged by the distrust of his supposed fellow Englishmen. He was unforgiving of their suspicion that he could not be fully English after showing himself so eager to conceal his Englishness, even if only for a time.

These suspicions drove him out of the position he had longed for, the counselship at Damascus, where "I was always at home" because "they always treat me as practically one of themselves." I can hear the longing in that "practically." Instead, he was posted to Trieste, in what he considered a damp, tedious exile. There, he spent years working on his translation of the Arabian Nights.

He died in October 1890. His tomb is in the shape of a Bedouin tent, incongruously pitched in marble in a cemetery outside London, as if he might pull up its pegs and go wandering again.

When I set myself the goal of becoming a classicist, I wanted to be entirely my disguise. I wanted to leave behind the parts of myself I was concealing. I thought that I would not make better friends than with the dead whose books I read. I showed only those parts of myself that fit the role I was playing. I thought that the other parts of me – my childhood, my desires, my frivolities, my strangenesses – would repeal anyone who caught a glimpse of them.

I took the Haji as a role model because I also thought that I was undertaking a pilgrimage, full of suffering and endurance, to obtain a new identity But now, I see the Haji as a cautionary tale. His life shows what happens when you keep exploring, hoping to find the perfect place for yourself, instead of making someplace imperfect home.

The Haji claimed to fear death if anyone penetrated his disguise, but I don’t know if I believe this. If someone discovered that he was not who he claimed to be, couldn’t he just have said he was a convert? Or converted on the spot? Perhaps, like me, what he feared would happen if he went undisguised was not death, but the far more frightening prospect of being seen.