Walking from Dunning to the Common of Dunning

Preamble

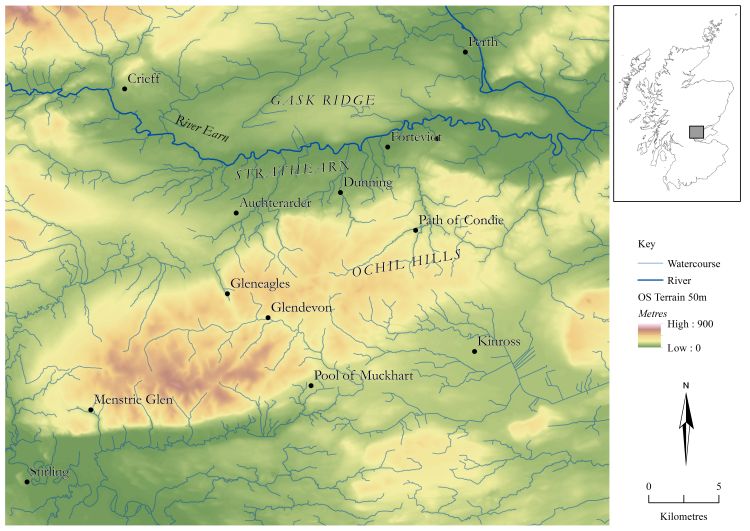

On 30 June 2016 I walked from Dunning to the Common of Dunning in the Ochil Hills of Perthshire in central Scotland. My overt aim was to trace the route of the 18th-century (and earlier) cattle and their herders from the lowland farms and estates of Dunning to their shared summer grazing up on the Common of Dunning. Much more than that, though, I wanted to experiment with new ways of engaging with and writing about landscape, moving away from the representation of a supposedly external landscape through photographs, maps and text (Hamilakis, 2013: 195). Instead, my idea was to use those same media to communicate a landscape performed as an active engagement among topography, plants, birds, soils, camera, my walking and sensing body, turf and stone dykes, fieldwalkers, farmers, rocks, colleagues, GPS satellites, memories, weather and many, many more.

Fieldwalking above Scores Farm, 12 June 2010 (Michael Given)

Below I present the narrative I wrote in my notebook while walking, along with automated photos taken by a GoPro camera, my route recorded by a GPS, and a range of other photos and maps from the wider field project. Before that, I will lay out the academic, social and landscape context of my walk, explore the sensory, performative and technological attributes of walking, and explain my methods. After the narrative, I will reflect on bodily engagement with landscape and how to communicate that.

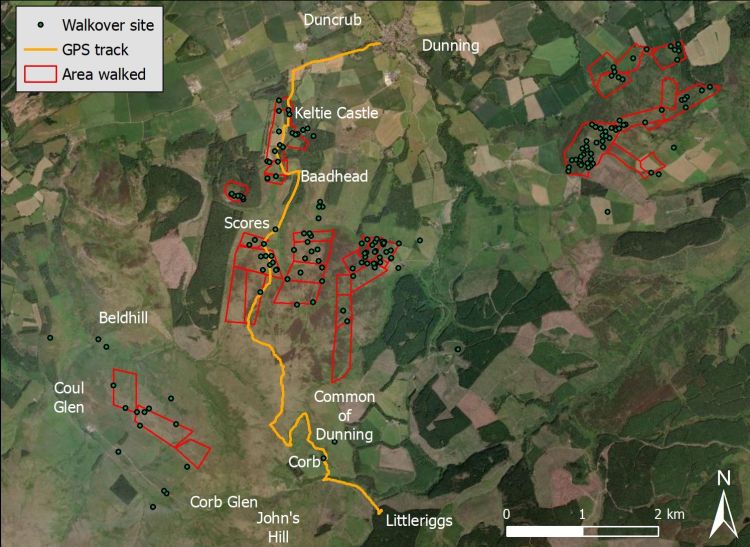

The walk took place during the last of ten seasons of walkover survey carried out as one relatively minor component of the University of Glasgow's Strathearn Environs and Royal Forteviot field school and research project. The northern slopes of the Ochil Hills, looking over the valley floor of Strathearn, were rich in evidence for Iron Age hillforts, post-Medieval agriculture and pastoralism, and all sorts of issues of mobility, interaction and complex interconnection. Of particular interest was the relationship between arable cultivation and the twice-annual passage of cattle in the 17th-19th centuries.

Location map (from Given et al., 2019: 85). Background: EDINA Digimap. (Oscar Aldred)

In 2016, the challenge we faced was how to write up these ten seasons of systematic but small-scale and rather slow-moving walkover, where training students and facilitating in situ landscape interpretation took priority over speed and coverage. By then our core team was Oscar Aldred (aerial archaeology and mobility), Kevin Grant (historical archaeology and biography), Peter McNiven (place-names and landscape naming), Tessa Poller (Iron Age and memory), and myself (walkover survey and interaction). In that brief 2016 season we spent several days walking, discussing and planning our publications. In our final discussion, we decided that part of our agreed solution was a thorough descriptive and analytical narrative in a conventional academic format (subsequently published as Given et al. 2019). But that, we all agreed, should be complemented by more creative and experimental narratives exploring the themes of mobility, place, interaction, and memory.

One way of stimulating such narratives is through walking, hence my being dispatched up the hill the next day. Walking is more than a bounded human activity directed by the brain and effected through the legs. It is an ongoing collaborative performance, where eyes, feet, muscles, legs and arms interact with the changing surface of the ground and respond accordingly (Wylie, 2007: 166). These connections and ongoing material encounters continually create movement and change, new connections, new shared bodies and 'thickets' of action (Lorimer, 2005: 88-89). The rhythms of walking are not banal repetitions but a rich and varied attunement between body and terrain that constantly senses, responds and adjusts (Vergunst, 2008: 115-17). Because of its utility in engendering connection and change, walking makes the perfect site for learning, particularly when accompanied by productive activities and listening to the narratives of those who have walked the trail and performed the actions before (Legat, 2008).

Fieldwalking in Keltie estate, 14 August 2012 (Michael Given)

The key interface in all these relationships and actions is the surface of the ground. This interface between walker and the world is textured with information, variation, hazards and the actions of those track builders and travellers who have gone before you, as felt through the soles of your feet and your muscles and bones (Vergunst, 2008: 114; Gibson, 2015: 431). Working within this interface, we are 'grounded', 'in touch with our surroundings' (Ingold, 2004: 330). We interact with the traces of our human and nonhuman predecessors, and our footprints rework those textures for others to follow, interact with and learn from (Legat, 2008: 44-46). There are many such textures in my narrative below.

There can be interesting cultural variations in this interaction. Ingold has noted the role of boots and western culture in coming between us and the ground (2004). So did the military engineer Edmund Burt, stationed in Inverness in the late 1720s to build a series of military roads across the Highlands. In one of his letters he notes the differences between his own passage across a bog and that of his Highlander guide:

I was harassed on this slough, by winding about from place to place, to find such tufts as were within my stride or leap, in my heavy boots with high heels; which, by my spring, when the little hillocks were too far asunder, broke the turf, and then I threw myself down toward the next protuberance: but to my guide it seemed nothing; he was light of body, shod with flat brogues, wide in the soles, and accustomed to a particular step, suited to the occasion. (Burt, 1998 [1754]: 166).

Whatever common experiences of boots or tussock-jumping I might have with Edmund Burt, what follows is not phenomenology. I have no claim or desire to represent past human (or indeed bovine) experience based on my own. I am more interested in cultural differences than putative human universals (Johnson, 2012: 277), and reject any Heideggerian nostalgia for local, bounded experience as somehow more 'authentic' than the interconnected world that constitutes human society (Wylie, 2007: 181-82; Ingold, 2011: 12). There is one aspect of the critique of phenomenological approaches in archaeology, however, that is very relevant here. I was, at least on the face of it, a single white male, apparently using his solitary landscape experience to represent that of a range of very different others (Johnson, 2012: 277). This is worth bearing in mind as you read, and I will return to it after the narrative. Perhaps there were other landscape actors up there with me, both human and nonhuman.

The most conspicuous aspect of my methodology was that I was weighed down with kit: a GoPro camera on a large bracket sagging from my shoulder, taking oblique photos of my right ear every minute; a hand-held GPS round my neck recording my route; my SLR camera for when I wanted more purposive photographs; map and compass; and, most importantly, notebook and pen. All this is emphatically not a technological barrier between me and the 'authentic' landscape. Rather, it was all part of the relational landscape: these artefacts and their various digital and analogue products were contributors to that ongoing, continuous negotiation between my feet, legs, muscles and balance, surface textures, paths, terrain, numerical abstractions such as grid references and bearings, and the wider social context (Lorimer and Lund, 2003).

It is certainly true, of course, that such tools can be used to transform personal experience in the landscape into authoritative fact, like the British Museum mission's notebooks in 19th-century Cyprus (Nikolaou, 2017: 85), or the industrialised processes of some commercial archaeology today (Caraher, 2019: 375). My aim was to subvert these tools of objectivization and use them to attend to and work with the landscape, and to incorporate something of that attention and collaboration into the experience of you, the reader and viewer.

For most of the walk I was experiencing landscape where I had worked over ten seasons. This meant it was full of fieldwork memories: for the archaeological surveyor, wisdom unquestionably sits in places (Basso, 1996). But these memories were linked together by my route in a way that I had never experienced before: they made me attend to the areas where we had worked from a whole series of different perspectives and angles. Wisdom, then, does not just sit in places: it is acquired and passed on by walking trails attentively (Legat, 2008: 47). The narrative evidently reflects my interests, but it also explores and responds to the stimuli in the landscape that awake those interests, such as paths, surfaces, birds, trees, sounds and smells, and the evidence for 18th-century agriculture and pastoralism.

I wrote the narrative as I moved, stopping whenever something struck me. I typed it up the same night with only very minimal editing, to try and keep any freshness and spontaneity of the landscape engagement that it might express.

Map of 'areas walked' and 'sites' from the walkover survey (2007-2015), with the GPS track of the walk on 30 June 2016. Background: ESRI. (Michael Given)

Dunning to the Common of Dunning

9.05am. Western Edge of Dunning

The GoPro attached, I'm dropped off by Tessa and Pablo on the outskirts of Dunning, to walk from Dunning to the Common of Dunning, following the route of the post-Medieval cattle herders. The first part is a short walk along the route of the Medieval road connecting Dunning with the Burgh of Auchterarder, now the B8062. I walk past the sign for Duncrub, the site of the Medieval estate, trying not to think about what the car drivers think of me with my GoPro sagging over my right shoulder and GPS dangling from my neck. The lone ash tree way up at Scores Farm is really clear from down here.

The walker/author writing at the beginning of the walk, with the GoPro on his shoulder (Pablo Llopis)

On my right is a handsome stone field wall, the stonework nicely picked out by the sun. There are tall oaks, sycamores and Scots pines on the left, along with the the continuous chatter of woodland birds: chaffinch, blue tit, wren, plus house martins darting past - the sound disrupted by the regular cars passing along the road.

The wind in a small sycamore by the road sounds loud in my ears, while distant chaffinches and woodpigeons call from the wood beyond the pea field on my right. The tree up at Scores Farm is still very prominent.

I pass Millhaugh, though I can't quite see the excavations from the road. There's a passing tractor and the continuous rushing sound of the burn at Millhaugh, then a blast of wind from a truck.

'Maggie Wall burnt here as a witch, 1657'. The monument is on a knoll by the road, with a wide view all round, from the Highland line in the North to the Ochils in the South. Many people would have seen her burn.

9.30am. Turn off to Keltie Castle

The turn off is marked by a beautiful, mature oak tree - a noisy one, too, in this wind. The avenue to Keltie Castle is attractive and inviting: the gentle curves and a line of estate-planted beeches lead both eye and feet along it. On the right is mixed woodland, mainly beeches, full of the song of chaffinches, dunnocks and a song thrush, with house martins swooping over patches of grass and a robin lurking in the undergrowth - all overlain by the wind in the beeches, rising and falling.

The avenue sweeps round past the overgrown mill lade, among oaks and beeches, with a first view over the square stone-walled improved fields of 19th-century Wester Keltie. The road is tarmacked and an easy, if solid, walk, and the smooth curves and roaring beeches continue to lead me along it. But then it forks off to the left, and I can't continue. That way lies Keltie Castle, and I'm not invited.

Survey Team at the fuller's earth tanks, with Keltie Castle behind, 15 August 2012

Instead, I fork right up a stone track, the difference immediately felt even through my heavy walking boots. I pass through the Western Keltie farmyard and out onto the improved fields that we surveyed four years ago - and am immediately greeted by the repeating calls of the carrion crows and the cries of the lambs.

My route continues up the rutted farm track, with its strange right angles as it respects the grid of the 19th-century improved fields. One short section is a hollow way, with oaks along one side. Could this be an older stretch? In the next field I cause a small stampede from the herd of cattle we met yesterday, including the famous bull who crushed a rival to death. Fortunately I don't seem to be in the competition. Half of the tree at Scores Farm is visible up above the skyline in front of me.

I'm passing out of the topmost 19th-century stone dyke, very dilapidated here, though there's a beautiful miniature rowan growing out of the top of the gatepost. I hear sheep and lambs, carrion crows calling, distant wrens and willow warblers, an aeroplane, and the wind in the trees and in my ears. Baadhead Farm is just appearing through the ash trees along the burn.

I follow a sheep trailing half its fleece on the ground into the farm, hearing the chaffinches and the wind in the copse of Scots pines that stands above the farm. This was a great early 19th-century venture into improved stock breeding, with the elegant curved walling joining two older buildings adding a touch of class to the yard. I'm beginning to feel like a cup of tea, but will press on to Scores Farm, whose tree is demanding I stop there and make it a landmark of this walk.

Baadhead Farm from Rossie Law, 16 August 2012 (Michael Given)

Up past the dark ranks of a tree farm of Sitka spruce, with a distant buzzard calling and the smell of young bracken.

10.12am. Gate at the top of the forestry plantation

We would always stop here when coming up with the students, partly for a breather, and partly to ask, 'What do you see?' They would look suspiciously up the hill, and perhaps suggest that might be something by the big tree. Apart from that, it was just a hill. Asked the same thing in the afternoon on the way down, and their faces would (often!) light up with the realisation of how much they could now read in the landscape after a day of engagement with it. They could spot enclosures, paths and cattle tracks, and talk about the interaction of soil, conifers, grass, farmers, cows, birds, herders, slope, water...

Students walking up to Scores Farm, 5 May 2010

If the GoPro shows an odd close up photo of a forest fence, that's because I was having a pee against it.

The wind in the Sitka spruce is a much more smooth and even hissing, very different from the rustle and clatter of the oaks and sycamores down in the estate policies. In front of me I'm hearing the meadow pipits, though there are still chaffinches calling behind me. The buzzard is still somewhere nearby.

10.25am. Scores Farm

Scores Farm, and a well-earned cup of mint tea from my stainless steel thermos, plus some Patterson's Rough Oatcakes bought in Sainsburys in Glasgow and transferred to a tupperware.

Sitting with the ash tree rustling in the wind behind me, there's a great view of the excavation site at Millhaugh with its two white tents, down at the edge of the valley floor below me. Last night I gave the students a talk on landscape archaeology and what we've been doing up here since 2007. Scores Farm always makes a good example: it's a substantial 18th-century complex with a range of rooms and a yard, a very solid square structure that is perhaps earlier, a later sheep pen built in the rubble, a small grain drying kiln, and of course the ash tree.

The tree is great for getting the students to think about nonhuman players in the landscape, and the importance of landmarks within a known landscape. One of the student supervisors mentioned that you could see this tree from the excavation site, and suddenly everyone in the front couple of rows got very excited and started crying out, 'The Tree! It's The Tree!' All on its own, this tree had become a known and meaningful landmark for the excavators 4km away on the valley floor.

Prehistoric site of Millhaugh being cleared of its topsoil, 8 June 2016. The arrow points out the tree at Scores Farm (Kenny Brophy)

After my tea and oatcakes, silently watched by the GoPro, I set off again. From Scores Farm there's a beautiful path, cut into the hillslope where necessary and sweeping round the spurs at a pleasant gradient. Turf dykes bound the pre-improvement enclosures on each side of me. The path swings round a spur and traverses down towards Thorter Burn, and as soon as I come round the corner I hear the sound of the burn, rising and falling slightly with the wind. On the far side, five cattle tracks converge to ford the burn, carefully excluded from the enclosures as they come down the hill.

Four years ago we did two wide transects up this hillslope, with a gap in the middle. It seemed a sensible sampling of the slope. Yesterday, Tessa, Steve, Kevin, Oscar, Marie and I came up to show Oscar what his aerial archaeology looked like on the ground, and to discuss how we would publish it all. And of course we found two beautiful farmsteads, one down by the burn, and the other with a large rectangular yard, right in the gap between the transects.

Farmstead above Scores, 29 June 2016 (Tessa Poller)

There's a splatter of a little waterfall as I cross the burn. What with that and the wind in my ears I can't hear the skylarks and meadow pipits any more. But on the other side an angry mistle thrush rattles at me, and I hear the meadow pipits again and distant sheep.

The path was hard to follow for a while, but the next stretch sweeps round a spur, zigzags carefully and heads on up the slope, all at a steady and comfortable gradient. There's a turf bank on the right now, and more enclosures starting 20m to my left. Was this corridor the route for the cattle?

I pause to change the GPS batteries, as a skylark sings above me. The GoPro will need doing soon as well. This wasn't a problem in the 18th century.

11.05am. Above the enclosures

This point seems to mark the end of the enclosures. I've lost the path now; I've just been following a sheep track running along a turf dyke. There are meadow pipits and skylarks everywhere; I'm glad I don't have to count them.

I'm relying on sheep tracks now. They're a bit meandering, and not much more than one boot wide, but they're better than the grassy tussocks and clumps of heather that lie on each side.

Coming over a rise, I catch a first sight of the wind turbines on the far side of Coul Glen. The question I'm trying to figure out is, where did the herders take the cattle from Keltie up to the Common of Dunning? The cattle tracks are very clear down by Scores Farm, where the cattle were funnelled between the enclosures. But up here they could spread out across the broad hillslope, so they were never concentrated enough to dig out the parallel V-shaped ditches that mark their repeated passage further down.

Cattle creating a track through the bracken on Beldhill, 29 June 2016 (Michael Given)

I'm following what I think is a sensible route, not losing height unnecessarily, with the intention of heading left and east across the head of Scores Burn. In fact, I've just found a quad bike track which seems to be doing the same thing.

It turned out that the quad bike track had a mind of its own, but I've found quite a good sheep track - for the moment, at least.

The sheep track wandered away, and I'm now humping over hummocks. There's a great view to the south-west, which means I'm totally exposed to the wind, and am having hat problems.

A bit further on, and I'm looking down (with tears in my eyes from the wind) onto the 18th-century enclosures at Hillend, and the long ridgeline running up and South that we surveyed two years ago. One of the rounded knolls ahead of me must be Corb Law, and so beyond them will be the steep-sided Corb Glen. I'm making faster progress than I thought.

Cattle at Beldhill, looking across to the Hillend enclosures, 29 June 2016 (Michael Given)

The wonderful parachuting song of the skylarks is continually in my ears. I'm coming down to cross a boggy area, where I can see the bog cotton shining white and waving in the wind. It is pleasantly springy underfoot as I squelch across the sphagnum moss, but then I have to do some tussock jumping to stay dry.

11.45am. An unexpected path

I've just met a quad bike track, but it's suspiciously sunk in, and there's a nice curve around the side of the knoll in front of me.

Yes indeed, this path is much too clever and comfortable to be a quad bike path.

The wind is cold and strong, there are some solid grey clouds and a few spots of rain. Time for a coat. Two minutes later I'm trying to put on my waterproof trousers with them blowing out like a double windsock.

A skylark kindly starts singing to tell me the shower is almost over. This path is smooth and comfortable, and helps me make good progress. There are occasional sheep shelters dug into the bank on its left-hand side, but they're clearly not much use on this slope in a south-westerly. It's good to put my hood back down. They're noisy things; you can hear nothing but them scraping on your ears. Now I can hear the wind in the grass, sheep and lambs, and the ever-present skylarks and meadow pipits.

So: where does this path go?

The path forks. The quad bikes seem to go right, while the cutting in the slope goes left. I'm going left.

It peters out soon, and I meet a fence. I think I've been led astray and am too far to the West, so I turn South-East and follow the fence.

12.15pm. Corb Law

Well, here's a magic spot. I'm on the top of Corb Law, where three fences show where Keltie Estate, Coul Farm and Corb meet. Opposite, across Corb Glen to the South, is John's Hill, where a perfect circle crowns the summit and marks the spot where four parishes meet. Down below to the East is the rich green of Corb Farm and the Common of Dunning, the destination of the herds coming up from Keltie and the other lowland estates. North-West is Chapel Hill, named not for a local chapel but because its income went to support a priest in Glasgow Cathedral. The green slopes of the valley are filled with turf dykes and enclosures, and the calling of crows and lambs.

I move off the top of the hill to find some shelter from the wind and have my lunch. Greek olives, German rye bread, Moroccan-style humous. It doesn't seem right, somehow. Of course a shower comes along immediately, but as it passes the sun shines on the pastures of Corb Farm and the Common of Dunning, and the grass glows with an astonishing, almost translucent bright green - all the more so because of the browns and greys of the moorland and harvested spruce all round it. Looking down at this vivid green lying in its sheltered bowl, it becomes clear why the Common of Dunning was so valued as summer grazing from at least the Medieval period onwards.

After my lunch I'm tempted to head straight down the steep hillslope to Corb Farm, but no herder would ever take cows down a slope so steep. So I retrace my steps slightly to head North again, and find an easier way down to the green valley floor.

I pass across Snowgoat Glen (more a ravine than a glen, and 'gote' was Scots for a watercourse), and it now seems clear that the best route to bring cattle over would be to cross east well before I did, and come down Corb Burn to Corb Farm and the Common that way. Opposite me, on the flank of Chapel Hill, is a beautiful example of a cattle route funnelled between two enclosures. Perhaps the cattle from Keltie met up with those from Findony further north and passed down this corridor.

As I come towards Corb Farm, with its barn roof covering a 19th-century farmyard with two ranges, the swish of the wind in the spruces behind the farm is very striking; at first I thought it was water. The carrion crows are very busy here, particularly up in the enclosures on the East side of Corb Burn. Peter, our placenames expert, says that Corb is from Gaelic crob or crobh, a hand or claw. I'm disappointed it's not corbie, a crow.

Circular sheep fank in front of Corb Farm, 24 June 2015 (Michael Given)

1.30pm. Forestry road

As I stand on the forestry road just South of Corb Farm, I listen to a duet between sheep and crows, backed by the wind in the spruces - very different from up on the moor. The sheep are stocked very densely, as can be seen by the quantities of dung I've just been stepping through. This might partly explain why it's so green, but on the other other hand, the land is clearly rich enough to support such a density of sheep.

The forestry road is hard, stony, sharp and uncomfortable. It takes a straight but unresponsive line to the Dunning-Yetts o'Muckhart road and the Littleriggs forestry commission car park, where I am to meet Tessa at 2pm. I'm 15 minutes early, so I sit on a stump of presumably spruce and listen to the very different sounds of the wind in the tree farm spruces and a little stand of young beeches by the car park, both capped by a robin singing from the spruces.

Like the nose-to-tail cows, I've been led all the way from Dunning to the Common of Dunning, by all sorts of roads, tracks, paths, sheep tracks, dykes and fences, many of them helpful and more or less leading in the right direction. And I'm very grateful. Without them I'd still be floundering among the tussocks up there on the moor.

A Visual Re-run

Five hours reduced to 49 seconds: video compilation of the GoPro photos taken at one-minute intervals. If the video does not play for you, here is a direct link.

Postamble

What really struck me on re-reading this narrative four years later was the diversity of participants in my walk, how place-specific many of them were, and how clearly you could hear those different places. Birds, trees, cattle and farmers all have their own favoured habitats, which are created and re-created not just by terrain and weather but by the habitus and history of plants, livestock, wild animals and humans. The medium of sound is particularly powerful in negotiating this complex mosaic: directional hearing allows the walker to distinguish moorland and farmland, for example, and different types of woodland.

The diversity of the paths that variously led and misled me across the landscape was astonishing, from formal networks of B-roads and estate drives to the more contingent meshworks of paths created through the agencies of cattle, sheep, walkers and quad bikes (Nuninger et al., 2020). All the time I was negotiating with these different landscape agents, deciding whose footprints to follow, being refused entry in one direction and led astray in another. For many walkers, including 18th-century cattle herders, negotiating a route is far more complex than following a marked road: one path peters out, and you cast around till you find another, until that too no longer serves your purpose and you need to branch out again.

How does my experience on 30 June 2016 translate into a deeper understanding of past landscapes? It has taught me how vital it is to engage with the specificities of place and path, which texture the ground and create the mosaic of practice and memory that constitutes landscape. By walking, we are not just responding and adjusting to the texture of the ground as a mechanical operation: we are setting up and continually renewing an interaction between our own movement and that of our predecessors, materialised in the dense, tangled network of routes, paths and footprints (Legat, 2008; Aldred, 2014; Gibson, 2015). Without past cattle, herders, quadbikes, dyke-builders, fencers, sheep, farmers and tussock-jumpers, my landscape experience would be dramatically different. Without past footprints, hoofmarks and tree roots, there is no landscape.

What footprints did I and my technological collaborators bring to this landscape? So often archaeological photography captures and enframes the landscape, erasing the experience of the fieldworker and replacing it with representations of sites and features and archaeologically constructed landscapes (Hamilakis et al., 2009). We originally thought the GoPro would provide a tidy sequence of such frames, representing a route rather than a site, a line rather than a dot. Its agency went far beyond our intentions, though. It sat like an incubus on my shoulder, peering out at the landscape past my right ear, tilting the horizon at a drunken angle, and occasionally staring up at the clouds or down at the ground. Worst of all, it insistently and annoyingly placed me and my ridiculous yellow hat in the otherwise pristine landscape. The guilty party has been captured on camera: the archaeologist is inescapably part of the landscape.

Perhaps I was the stereotypical western white male imposing his narrow-minded representation of the landscape on others, like that archetypal 'phenomenologist of Wessex, wandering lonely as a cloud' (Johnson, 2012: 277). But perhaps, in some respects, I wasn't. After ten seasons of walkover survey, the landscape for me was full of other voices and actions: the cheeriness of students working in a downpour; the farmer pointing out significant trees; the cattle heading nose to tail up the hillside; the colleague demonstrating how well an experienced eye can read the archaeological landscape; the aural texture created by dense and complex bird song; the landowner who knows exactly where and in what weather an unwary Land-Rover gets stuck. Even up on the high moor, I was never walking alone.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to all those who in many different ways walked with me: Oscar Aldred for the inspiring discussions about mobility and landscape, and the location map; Kenny Brophy, Pablo Llopis and Dene Wright for the photographs; Chris Dalglish for teaching me to read Scottish post-Medieval landscapes; Andrew Given for editing the video; Kevin Grant for the microhistories; Peter McNiven for his insights into landscape through place-names and language; Rachel Opitz for the path discussions and help with Markdown; Tessa Poller for the creative ideas, encouragement, hardware, and transport; Calum Rollo, the owner of Keltie estate, for historical information, logistical support, and permission to do fieldwork; and the numerous students over the years who carried out the fieldwork and discussed the landscape cheerfully and enthusiastically in all weathers. Thanks also to Historic Environment Scotland for funding the Strathearn Environs and Royal Forteviot project.

Works Cited

Aldred, O. 2014. Past movements, tomorrow's anchors: on the relational entanglements between archaeological mobilities. In: J. Leary, eds. Past mobilities: archaeological approaches to movement and mobility. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 21-47.

Basso, K.H. 1996. Wisdom sits in places: notes on a Western Apache landscape. In: S. Feld and K.H. Basso, eds. Senses of place. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press, pp. 53-90.

Burt, E. 1998 [1754]. Burt's letters from the north of Scotland. Edinburgh: Birlinn.

Caraher, W. 2019. Slow Archaeology, Punk Archaeology, and the 'Archaeology of Care'. European Journal of Archaeology 22: 372-385. https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2019.15

Gibson, E. 2015. Movement, power and place: the biography of a wagon road in a contested First Nations landscape. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 25: 417-434. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774314000791

Given, M., Aldred, O., Grant, K.J., et al. 2019. Interdisciplinary approaches to a connected landscape: upland survey in the Northern Ochils. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 148: 83-111. https://doi.org/10.9750/PSAS.148.1268

Hamilakis, Y. 2013. Archaeology of the senses: human experience, memory, and affect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hamilakis, Y., Anagnostopoulos, A. and Ifantidis, F. 2009. Postcards from the edge of time: archaeology, photography, archaeological ethnography (a photo-essay). Public Archaeology 8: 283-309. https://doi.org/10.1179/175355309X457295

Ingold, T. 2004. Culture on the ground: the world perceived through feet. Journal of Material Culture 9: 315-340. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1359183504046896

Ingold, T. 2011. Being alive: essays on movement, knowledge and description. London: Routledge.

Johnson, M.H. 2012. Phenomenological approaches in landscape archaeology. Annual Review of Anthropology 41: 269-284. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145840

Legat, A. 2008. Walking stories: leaving footprints. In: T. Ingold and J.L. Vergunst, eds. Ways of walking: ethnography and practice on foot. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 35-49.

Lorimer, H. 2005. Cultural geography: the busyness of being 'more-than-representational'. Progress in Human Geography 29: 83-94. https://doi.org/10.1191%2F0309132505ph531pr

Lorimer, H. and Lund, K. 2003. Performing facts: finding a way over Scotland's mountains. In: B. Szerszynski, W. Heim and C. Waterton, eds. Nature performed: environment, culture and performance. Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 130-144.

Nikolaou, P. 2017. Authoring the ancient sites of Cyprus in the late nineteenth century: the British Museum excavation notebooks, 1893-1896. Journal of Historical Geography 56: 83-100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhg.2017.02.006

Nuninger, L., Verhagen, P., Libourel, T., Opitz, R., Rodier, X., Laplaige, C., Fruchart, C., Leturcq, S. and Levoguer, N. 2020. Linking theories, past practices and archaeological remains of movement through ontological reasoning. Information.

Vergunst, J. 2008. Taking a trip and taking care in everyday life. In: T. Ingold and J. Vergunst, eds. Ways of walking: ethnography and practice on foot. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 105-121.

Wylie, J. 2007. Landscape. London: Routledge.

Cover Image Approaching Scores Farm (Michael Given)

Masthead Image Fieldwalkers above Keltie Wood, August 2009 (Michael Given)