Hearing Corwin Hall: The Archaeology of Anxiety on an American University Campus

Introduction

Hearing Corwin Hall is a multimedia work composed and performed by Michael Wittgraf. The piece is based on a two-month long archaeological, architectural, and archival documentation project of two, adjoining, double buildings on the University of North Dakota’s Grand Forks campus: Robertson-Sayre Halls, built in 1929 and 1908 and Corwin-Larimore Halls, built in 1909 and 1910. The buildings were originally part of Wesley College, an independent, Methodist institution which moved to Grand Forks in 1905 and forged a close affiliation with UND. Sayre and Larimore served as men’s and women’s dorms respectively and Robertson and Corwin hall housed offices and classroom space. Corwin Hall also included music rehearsal rooms and the college’s recital hall, a fine room with a capacity of 100. These four buildings stood as the core of Wesley College from its founding until 1965.

In 1965, the University of North Dakota (UND) acquired the buildings which stood adjacent to the university’s campus and until 2016, they housed various departments, programs, labs, classrooms, and offices. In 2018, UND demolished the buildings as part of an effort to reduce the campus footprint by eliminating buildings burdened with significant deferred maintenance costs. Prior to their demolition, a team of students in collaboration with William and Susan Caraher formed the Wesley College Documentation Project to study the buildings and the objects left behind. The university’s facilities department provided virtually unfettered access to usually locked buildings in the time between their abandonment and their demolition. This project produced a small archive of descriptive data, photographs, and analysis, coordinated two public events associated with the Wesley College campus, and published a photo essay that commemorated and critiqued the buildings, their history, and the contemporary financial and cultural situation at UND (Atchley 2018).

This article introduces the work of the Wesley College Documentation Project in the context of a piece of music by Michael Wittgraff titled, “Hearing Corwin Hall.” This work integrates historical and contemporary images of the buildings, audio drawn from the project’s public events, and the acoustic signature of the Corwin Hall’s recital room which although compromised over its 100-year history preserved audible and visible traces of its past function. Michael Wittgraf’s ”Hearing Corwin Hall” is also set against the backdrop of significant institutional, administrative, and cultural changes at UND and in higher education more generally. A more thorough consideration of the work and the Wesley College Documentation Project appears in the discussion below.

Video 1: Hearing Corwin Hall. Michael Wittgraf. An archived copy of the video is available at The Internet Archive.

Discussing Corwin Hall

College campuses are anxious places.

The looming demographic downturn, changing funding priorities among donors and legislators, and a whelming tide of anti-intellectualism in American life have contributed to a growing sense of uncertainty surrounding the future of higher education. Many college campuses, at least in the United States, have initiated strategic planning, prioritization, and other buzzword-framed efforts to reimagine programs, to cut costs and find new efficiencies, and to help institutions navigate an uncertain future. Each year, another crop of books appear promising to diagnose, mitigate, or manage current or anticipated crises in funding, enrollment, teaching, research, and student expectations. These local, national, and global trends fuel a now ubiquitous understand that higher education is an industry in transition (or even in crisis) and that the college campus of the future will look very different from the campus of today (e.g. Staley 2019; Fabricant and Brier 2016; Newfield 2017; Bowen and McPherson 2016).

Figure 1: Photograph courtesy of Wyatt Atchley

The tensions between the past and the future have left their marks across university campuses. State universities, in particular, have long situated themselves at the intersection of progress and tradition (Labaree 2017; Dorn 2017). They celebrated both cutting edge research and a deep commitment to traditions across the rituals of college life, the architecture of campus, and the academic and research programs undertaken by students and faculty. College Gothic buildings rub shoulders with the latest in post-modern architecture, the century-old rites of commencement and graduation accommodate spectacles of more radical inclusivity and reconciliation, online teaching introduces students to Classics and calculus, and researchers on Shakespeare share library budgets with new programs in nanotechnology and unmanned, autonomous vehicles. The constant efforts to negotiate change across campus likewise contributes to anxious moments when the rear guard and the avant-gard scuffle to secure resources for programs and students. It is hardly an exaggeration to see the contemporary university as a liminal zone where everything is always on the verge of change both in the present and in the past (Bettis et al. 2005).

Figure 2: Photograph courtesy of Wyatt Atchley

In many cases contemporary college students remain liminal figures as well. They live communally in dormitories or rental housing, and their lives revolve as much around the rhythm of the academic year as off-campus employment, family life, and socializing. As a result, many college students neither bear the full economic and social responsibilities of adulthood nor enjoy the living arrangements and security of childhood. Archaeologists and historians have long observed in their work on college campuses the tension between independence and control. A number of the contributors to Skowronek and Lewis’s (2010) have noted the tensions between the formal rules that governed student behavior and the realities of campus life where drinking alcohol, for example, might be banned but nevertheless maintained a material trace in archaeological deposits (Skowronek and Hylkema 2010; Davis et al. 2010). The role of fraternities, and university life more broadly, in prolonging childhood and suspending adulthood comes to the fore in Laurie Wilkie’s brilliant archaeology of a fraternity at the University of California (Wilkie 2010). She frames her account of life at the Zeta Psi fraternity with invocations of Peter Pan, a quintessentially liminal character, and emphasizes the role played by fraternities in the social transition of male students into adulthood. Students learn to navigate the responsibilities of adult life without fully giving up the structures of student life or parental protections which are often transferred to institutions who provide food, housing, and appropriate social opportunities. Carla Yanni’s recent study of the architectural history of campus dormitories shows how these building sought to follow not only established expectations of domesticity, but also the need to control student behavior (Yanni 2019). Even beyond the structured, but private domestic space of dormitories and fraternities, college campuses in general often locate the liminal experience of college students in areas not entirely public and integrated into the fabric of their community or entirely private and set apart.

Figure 3: Photograph courtesy of Wyatt Atchley

Thus, college campuses embody a number of forms of liminality that emphasize the current sense of institutions in transition alongside the historical tensions between progressive values and traditional practices and student experience of life as not quite entirely adults. As mid-century anthropologists have taught us these liminal situations often contribute to a sense of anxiety which underscores the vulnerability and strangeness of institutions and individuals that resist clear definition and stand “betwixt and between” various social statuses (Turner 1969; Turner and Turner 1978; see, of course, van Gennep 1909). Societies often seek to resolve and contain liminal individuals and groups through formally structured ritual practices, confinement, and other forms of social limiting designed as much to protect society from the destabilizing entities as to confer a temporary status on those outside of traditional categories. Rites of passage, for example, frequently mark the successful navigation from one status to another and resolve the tension of liminal transitions with celebration. At the same time, we continue to treat individuals and groups who are unable to escape from the liminal status with deep suspicion.

Figure 4: Photograph courtesy of Wyatt Atchley

The Wesley College Documentation Project did not begin with the intention to explore anxiety or liminality on an American college campus. In fact, much of how we have presented our work in this article emerged over the course of our fieldwork and through our engagement with the buildings, the performances and conversations that we shared, and the creative works that our project produced. The project began with a 1-credit Honors “pop up course” that ran in the spring of 2018. This course paralleled an Honors class dedicated to studying the UND budget which had undergone significant changes over the preceding years and, in hindsight, created a significant amount of liminal anxiety on campus. The worsening economic situation in the state, changes in the university’s administration, and a relatively unsympathetic legislature led to budget cuts and significant changes on campus. For example, the university scheduled a number of old or underutilized buildings for demolition to help reduce the campus footprint, and the four Wesley College buildings were among these. For many students, the icon of the budget cuts on campus was the athletic department’s decision to cancel several prominent scholarship sports teams — including women’s ice hockey. Michael Wittgraf and William Caraher, faculty in the College of Arts and Sciences, experienced the defunding of two programs. While Wittgraf was chair of music, he endured the cancelation of the popular music therapy major. Caraher oversaw the defunding of the graduate program in history as Director of Graduate Studies and took on the editorship of the century-old literary magazine North Dakota Quarterly just as the college laid off its long-time managing editor and eliminated support for publication and the faculty editor (Caraher 2018). Many of the students in the class came from UND’s Honors Program which also underwent significant programing and staffing changes during this time including the move from its longtime home in the basement of Sayre Hall to a new space outside of the central campus. The changes were so pervasive across campus that they prompted a former colleague in the English Department to write an article in the Chronicle of Higher Education titled, “My University is Dying” (Liming 2019).

Figure 5: Photograph courtesy of Wyatt Atchley

As Pamela Bettis and colleagues have shown, during intense periods of transition, the sense of liminality contributes to a heightened sense of anxiety among faculty (Bettis et al. 2005). Ann Cvetkovich generalizes this even further in her 2012 book, Depression: A Public Feeling, which recognizes the stresses of academic life as a contributing factor for anxiety and depression especially among marginalized groups. The vagaries of the job market, the competition between scholars for accolades, grant money, and advancement, and the constant threat of budget cuts and dismissive rhetoric directed at the arts and humanities creates an environment which is not conducive to the very academic productivity expected on a university campus. Looking beyond the clinical language of depression (and its pharmacological solutions), Cvetkovich emphasizes the social and political factors that contribute to feelings of anxiety, burnout, and depression by unpacking her own experiences as a new faculty member. By making public the feelings associated with depression Cvetkovich does not seek to solve the problem of depression and anxiety, but to identify its roots in a system that trades in the “cruel optimism” of capitalism (Berlant 2012). She sees in religion, ritual, routine, and attention to the daily tasks of living strategies to survive this system, whether on a college campus or in the 21st-century world, and foster reserves of energy and resolve to push for justice.

Figure 6: Photograph courtesy of Wyatt Atchley

The anxieties of the 21st-century university campus and the particular situation at UND formed a common backdrop between students in the Honors class on the UND budget, the class documenting Wesley College, and faculty collaborators. The tie between the university budget, the abandonment of these two buildings, and their current state encouraged us to document, in as many ways as possible, the architecture and material culture of these buildings, their history, and the process of abandonment. In this attention to detail, we were not alone. Despite their hectic work across the changing UND campus, the Facilities department consistently found time to provide us with access to the buildings and offered their considerable expertise concerning the physical fabric of the buildings. Our class also attracted positive attention from across campus and in the local media. Despite the praise and interest surrounding our work around these century-old buildings and the team’s dedication to the past, a sense of sadness pervaded the project.

Building Corwin Hall

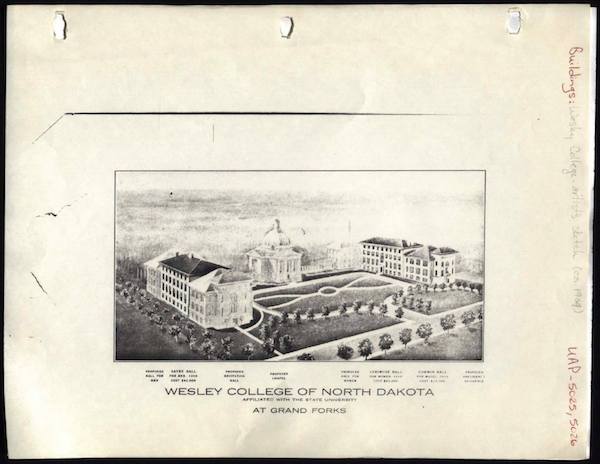

Wesley College was founded in 1892 as Red River Valley University in Whapeton, North Dakota (for the early history of Wesley College see Robertson 1935; Henry 1948). In 1905, a remarkable agreement between the president of the Red River University, Edward Robertson, and the president of UND, Webster Merrifield, led to the college moving to Grand Forks, changing its name to Wesley College, and entering into a distinctive coeducational relationship with UND. Students enrolled in Wesley College would live in the college’s two dormitories and take classes in religion, Bible, elocution, and music on the Wesley College campus. They would also take classes at UND and ultimately receive a degree from that institution. The promise of this relationship allowed Robertson to raise sufficient funds from a range of local and national donors to build the college campus in Grand Forks. He named the builds after their donors: A.J. Sayre was a West Coast lumber baron and N.G. Larimore and Stephen Corwin, whose daughter studied music at Northwestern University, were wealthy farmers from North Dakota. Robertson contracted New York City based architect A. Wallace McRae who planned a campus featuring two paired buildings, Corwin-Larimore and Roberston-Sayre, in the then-fashionable Beaux Arts style. The two, double buildings would stand opposite each other across a grass courtyard. A drawing found in the Wesley College paper in the UND archives indicated future plans for a large domed building which would link the two paired buildings and close the courtyard on its north side.

Figure 7: Artist Illustration of the Wesley College Campus from 1909. University Archives Photo 5025. Elwyn Robinson Department of Special Collections. Chester Fritz Library. University of North Dakota. Grand Forks, ND.

Figure 8: The Wesley College Campus in March 2018 facing north. Robertson/Sayre Hall to the left and Corwin/Larimore Hall to the right. The building in the middle dates to the early 21st century.

Figure 9: Robertson/Sayre Hall facing northwest. March 2018.

Figure 10: Corwin/Larimore Hall facing northwest. March 2018.

Video 2: Drone flyover of the Wesley College Campus. April 2018. Video courtesy of the University of North Dakota. An archived copy of the video is available at The Internet Archive.

In 1908, 1909, and 1910, three quarters of four paired structures opened for use: Sayre, Larimore, and Corwin Hall. Sayre Hall was a men’s dormitory. Larimore Hall a women’s dormitory and connected to Corwin Hall which featured offices, classrooms, and a recital hall for music. In 1929, the final building of the campus plan was built, Robertson Hall, which connected to Sayre Hall and completed the matched pair of two-building structures. John Hancock, a UND alumnus and financier who became the first non-family partner at Lehman Brother, funded the construction of Robertson Hall and his children lived in Sayre and Larimore Halls. During its time as a dormitory, Sayre Hall also housed Pulitzer Prize winning playwright Maxwell Anderson and aviator Carl Ben Eielson who remain two of the university’s most distinguished alumni.

Wesley College was never a thriving institution, but it endured the Great Depression in part because of the tireless efforts of its recently retired president Edward Robertson to solicit donations from supporters throughout the 1930s. This collection of letters from 1935 (Robertson 2018) offers a taste of Robertson’s efforts to secure funding for the college among his friends and colleagues.

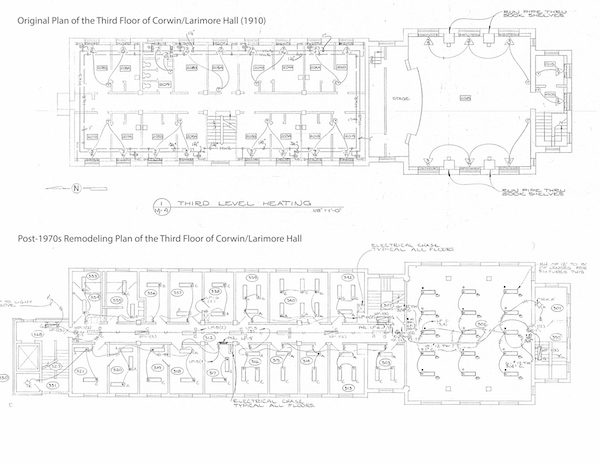

During World War II, the campus served as the home to the 304th College Training Division of the Army Air Corp during the World War II. As it entered the post-war period, however, its finances had become ever more fragile. In constrast, by the early 1960s, UND was developing into a modern comprehensive university (Robinson 1971). It had build modern dormitories, created its own music department, and eclipsed Wesley College in size and amenities. In 1965, UND purchased Wesley College and integrated its remaining academic staff into the university. The buildings continued to serve their original functions until 1976, when UND converted all four buildings to classrooms and faculty offices. While the original plan of Sayre and Robertson Hall remained largely visible for as long as they stood, Larimore and Corwin Hall underwent more significant modification. The original plan of the paired building limited access to the women’s dormitory in Larimore Hall from the offices and classrooms of Corwin Hall. The new plan opened up access between the buildings as Larimore Hall was largely given over to faculty offices.

Figure 11: The original plan of Corwin/Larimore Hall (top) and the final plan of the building after its 1970s remodeling. University Archives 75, Box 3, Folder 19. Elwyn Robinson Department of Special Collections. Chester Fritz Library. University of North Dakota. Grand Forks, ND.

Figure 12: Corwin Hall recital room facing north.

Figure 13: Corwin Hall recital room facing northwest

Figure 14: Corwin Hall recital room facing south.

In the original Corwin Hall plan, the second floor recital hall featured a large central space with a gently vaulted ceiling flanked on the east and west sides by narrow arched corridors set apart by a pair of square pillars. The northern side of the hall comprised a proscenium arch separating a shallow vaulted stage area from the main hall. On the south side, the room featured a central doorway that opened onto a landing at the top of the main stairwell in the building. The room was originally equipped with pipe organ and Steinway grand piano. As the recital hall for Wesley College, the room possessed a certain sensitivity to acoustics, a sense of style, and a monumentality that would have reinforced the Classical lines in the building’s Beaux Arts architecture. Its size and formality allowed it to also serve as the college chapel.

Even the conversion of the recital hall to a classroom could not completely undermine its former style. The square piers, gently vaulted roof and various traces of wood trim remained visible in the room, although the northern side of the room was interrupted at the proscenium arch with solid wall pierced by a single door. This modification to the building created a small office and a new stairwell flanking the east and west, respectively, of a hallway that continued north into Larimore Hall. A U-shaped track of HVAC ducts concealed behind an inelegant drop ceiling ran around the vaulted ceiling of the room and the once large widows on the east and west sides were filled in and smaller more modern windows installed. These changes produced a large classroom with a capacity of almost 100 students which since the 1980s was mainly used by the psychology department whose offices and labs were throughout the modified building.

Performing Corwin Hall

By the time that the Wesley College Documentation Project began the buildings were already abandoned. The final departing faculty member from the psychology department had reluctantly pulled up stakes from Corwin-Larimore Halls only after he had sent off the last grant application of the season. The honors program and campus technology services had departed Robertson-Sayre Hall at around the same time. Thus the buildings themselves entered a period of liminality. The traces of their prior use continuing to linger in the rooms, offices, and hallways, but at the same time, their fate was sealed and asbestos mitigation and demolition scheduled. The objects left behind and the histories of these buildings seemed to have reached a clear end point. Offices with mid-century desks, 21st-century chairs, particleboard books shelves, bulletin boards, window air-conditioner units, and locked filing cabinets still preserved the imprints of their former occupants. Classrooms remain filled with rows of abandoned chairs too outdated for even state-university surplus and tables and lecterns long ago supplanted by high-tech ”teaching stations.” The labs of the third floor were filled with antiquated computers, dense tangles of obsolete connectors, and abandoned equipment of uncertain age and function. The content of these spaces reflected not only their present abandoned state, but revealed that some forms of abandonment had began long before the university scheduled these buildings for destruction.

Our encounter with Corwin and Larimore Halls was not only infused with its failure to survive as an independent institution and its impending erasure from campus, but also by the objects that were left behind which served as a diachronic reminder that campuses exist in a state of constant flux. Encountering this in the liminal space of the Wesley College buildings amplified our sense of anxiety across campus. In an effort to recognize the liminal state in which these buildings existed, we decided to combine our work with two events designed to mark out both contemporary and past changes on campus. The first event centered on recognizing that Sayre Hall was renamed in the 1920s for Harold H. Sayre who was the son of the building’s donor, A.J. Sayre. Harold Sayre had been killed in World War I and the building stood as a memorial to his sacrifice. To commemorate the demolition of this building almost exactly a century after the armistice that ended the Great War, we invited campus dignitaries, officials from the Grand Force Air Force Base and the city, as well as faculty, staff, and students to a short ceremony designed to recognize the end of this memorial building. The event involved brief reflections on the building, the sacrifices of veterans, and a bagpiper on a beautiful spring day. The program that we circulated also included a poem composed by Sayre’s pilot who credited Sayre’s bravery with saving his life when their plane was shot down in France. The poem was found in the university archives by the students working on our project.

Figure 15: The presentation of colors at the Harold Sayre commemoration service outside Sayre Hall.

Simon Murray’s recent book, Performing Ruins (2020), considers the feelings that ruins evoke when they serve as the setting for performances. While Murray acknowledged that the definition of ruins is ambiguous, he nevertheless noted that the term typically described buildings that were in movement or between the states of use and terminal collapse. In this context, the Wesley College buildings, while still standing and intact, were ruins as their abandonment, neglect, and fate combine to create a sense of inevitable decline. As Wyatt Atchley’s photographs, which accompany this article demonstrate, the ruins of Wesley College evoke an uncanny feeling. This is typical in liminal spaces where confused encounters with the familiar and unfamiliar are common. In Murray’s work, he notes that the occupation of ruins through their performance seeks in some cases to suspend these spaces and to arrest, for a moment, their movement into oblivion (288-289). The ceremonies associated with Sayre Hall implicitly invited the community to consider the parallel between Sayre’s death and the destruction of his memorial. By accentuating Sayre’s memory, the ceremony briefly reversed the inevitable flow of time toward the building’s destruction and the memorial’s erasure from campus. This also presented an opportunity to critique the changes taking place on campus by drawing attention to buildings prior to their destruction. The tendency for contractors to demolish campus buildings in between terms or in the summer months when students and faculty are not on campus is often a concession to safety, but it also has the effect of making buildings seem simply to disappear. Our ceremony made Sayre Hall and the Wesley College campus hypervisible at least for a moment.

The second performance associated with the Wesley College buildings was a final concert in the Corwin Hall recital room. William Caraher introduced the larger project and the selection of songs with brief remarks at the beginning of the event. Then, Michael Wittgraf performed several songs from the Methodist hymnal on an electronic keyboard to a small audience who sat amid stacks of abandoned classroom chairs, tables, and scraps of paper. At the end of the performance, he recorded a series of sounds designed to capture more clearly the acoustic signature of the space. To record the room’s signature and the concert we arranged seven microphones both within the recital hall, but also throughout Larimore Hall and on the landing outside the southern entrance to the room. Our goal was to produce an acoustic archaeology of the room by capturing not only whatever character of the original recital hall remained, but also the sound of the transformed space. In this way, we use acoustic recording methods in a similar way to the visual recording techniques typically used by archaeologists to record buildings and landscapes.

The inspiration for the recording came from several recent efforts to capture the acoustic character of Byzantine churches in Greece and Turkey (Papalexandrou 2017; Gerstel et al. 2018). These projects typically involved sophisticated recording strategies and technology as well as choirs performing period appropriate music. This work explicitly sought to reconstruct ancient, Medieval, or Early Modern “soundscapes” with an ear toward understanding more fully past experiences in significant buildings (Smith 1999). It was appealing to imagine that we could reconstruct the original acoustics of the now-compromised Corwin recital room, but we neither had the technology nor the time to attempt such an ambitious sonic simulation. Instead, by performing in the Corwin Hall room, we aimed to document the room’s abandoned and transformed state. Like the project’s broader effort to recognize the traces of use throughout these buildings, the acoustic signature of the room would capture, even if in subtle and indistinct ways, the sounds of its transformation, neglect, and abandonment. By performing this event with an audience we once again sought to pause the inevitable progress of the building toward demolition and abandonment. We also sought to locate bodies in the acoustic space of the building invoking its history as a recital hall, a classroom, and part of a bustling department and campus. In short, our recording both recognized the terminal status of the building and the room, while also capturing its transformations. The songs were superficially familiar, but the transformed space rendered them uncanny.

Video 3: The final Corwin Hall concert performed by Michael Wittgraf. Video courtesy of Susan Caraher. An archived copy of the video is available at The Internet Archive.

Hearing Corwin Hall

The event in the Corwin Hall recital room was not the final performance associated with the project. The recordings of the music and the sounds of the rooms became the basis for a multimedia performance work called ”Hearing Corwin Hall” which captured the liminal state of Corwin Hall as well as the anxiety present on our university campus.

These performances, in turn, became the basis for the video associated with this article. By using the acoustics of Corwin Hall as a filter for the audio component of performance, Wittgraf located the anxiety present in the recital hall’s liminal and compromised space. It also embodied the anxiety endemic on university campuses and in the particular situation on UND’s campus created a heightened sense of anxiety.

”Hearing Corwin Hall” told the story of the buildings and the Wesley College campus. The construction of the buildings, triggered by the placement of a brick on the stage at the 1:30 mark interrupted the peaceful chorus of crickets that comprised the first 100 seconds of the piece. The introduction of the sounds of motors and passing traffic along side the crickets and, then, a looped track of Caraher’s voice marks the growing bustle of a busy campus and its purchase by UND in the 1960s. The initial placement of a sledge hammer on bricks, then brings in the organ and Sheila Liming’s bagpipe from the Sayre Hall memorial ceremony as the din of traffic and Caraher’s looped voice continues to add a kind of frenetic intensity. The powerful blows with the sledgehammer at the 6:40 mark the start of the building’s destruction which then slowly descends into the reverberation acoustics of the Corwin Hall. The last four minutes of the piece lingers offering a false sense of resolution. The buildings are gone, but their echoes persist.

Conclusion

The piece seeks to communicate in non verbal ways the history and archaeology of Corwin Hall and to emphasize the anxiety and tensions that surrounded the building’s destruction. This approach to archaeology with parallels recent interest in the “affective turn” which have sought to explore and communicate emotions and feelings not only associated with trauma, but also of daily life. While the scholarship on affect in the humanities is vast, the work of Ann Cvetkovich and her efforts to document publicly the depression, anxiety, and stress associated with academic life has resonated strongly with this project. “Hearing Corwin Hall” interweaves the pervasive anxiety of life on UND’s campus with the history and demolition of the four Wesley College buildings.

The work of the Wesley College Documentation project and its attention to the detailed documentation of these buildings evokes both Cvetkovich’s strategies for survival and the recent calls for an emotive and affective archaeology. The performance of public rituals amid the ruins of Wesley College and the careful routine of documenting their contents allowed us to “keep moving” and for a moment engage with a set of material realities that anchored our drifting despair in the past and in the present (Cvetkovich 2012:210-212). By communicating our experiences we sought to explore how documenting the Wesley College campus could center the role of affect in producing knowledge of the past. For Sara Perry, enchantment lies at the core of archaeology’s ability to produce action (2019). Both ”Hearing Corwin Hall” and the Wesley College Documentation Project used the enchanting experience of ruins to articulate the anxiety of campus life. It does so by using a range of non-verbal techniques anchored in the reproduction of the acoustic character of the recital room and the various events associated with the Wesley College Documentation Project. The techniques used in Hearing Corwin Hall paralleled those discussed by Ruth Tringham in her recent article on creating ways to explore the deep past that do not rely on the use of contemporary language. Tringham’s willingness to create engagements with the past that allow for significant ambiguity through which the audience has opportunities for an emotional response, free play of the imagination, and personal reflection often lost in traditional archaeological texts, descriptions, and reconstructions (2019). We hoped that Hearing Corwin Hall allows listeners to not only experience some of our own encounters with these buildings, but also gave the listener space to think about the changes on campus is distinctive and personal ways. The ambiguity of the electronic sounds, the garbled looped voice, and the abrasiveness, abruptness, and density of the piece invites strong responses.

In many ways, Hearing Corwin Hall as a model for the enchanting and affecting potential of heritage, does not entirely avoid appealing to “crisis based” or “heritage at risk” narratives. As Cornelius Holtorf has argued crisis based narratives which seek to communicate a sense of urgency by viewing of cultural heritage as a limited and ever shrinking resource has only a limited potential to motivate more expansive, inclusive, or resilient views of the community (Holtorf and Kristensen 2015, Holtorf 2018). At the same time, by seeking to commemorate and recognize the destruction of the Wesley College buildings on UND’s campus through conventional documentation practices as well as performances, photographs, and the Hearing Corwin Hall recording we situated the demolition of these buildings within a larger conversation centered on the anxieties that liminal states induce. Our efforts to document the changes to these buildings prior to their destruction by using the compromised acoustics of the recital hall as filter for Hearing Corwin Hall serves as a reminder that campuses have always been the locations of change and art, music, history, and archaeology offer ways to bring attention to both the emotional impact of the contemporary situation as well as the resilience of the campus community. Hearing Corwin Hall makes clear that the loss of the Wesley College buildings contributed to a sense of local trauma. Performances offer one way to recognize, communicate, and ultimately mitigate the impact of the continuous trauma of liminal anxiety on our campus.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks goes to the students who participated in the Wesley College Documentation Project and my class on the University of North Dakota budget. They both inspired and challenge me, and their persistent and insistent interest reminded me that this project was worthwhile. Susan Caraher assisted on that project in her capacities as an archaeologist and as the Historic Preservation Coordinator for the city of Grand Forks, North Dakota. Joseph Kalka provided support for the project both in the buildings and in Special Collections. The staff of the Elwyn Robinson Department of Special Collections at the Chester Fritz Library at the University of North Dakota exceeded their formidable reputation for professionalism and collegiality in their work to guide the authors and the students through their collection. The Facilities Management staff at UND was enthusiastic and supportive throughout.

Bibliography

Atchley, Wyatt. 2018. Images of Austerity. North Dakota Quarterly 85: 124-126.

Berlant, Lauren. 2012. Cruel Optimism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Bettis, Pamela, Michael Mills, Janice Miller Williams, Robert Nolan. 2005. Faculty in a Liminal Landscape: A Case Study of College Reorganization. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies 11.3: 47-61 doi: 10.1177/107179190501100304

Bowen, Bruce and Michael S. McPherson. 2016. Lesson Plan: An Agenda for Change in American Higher Education. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Caraher, William. 2018. Humanities in the Age of Austerity: A Case Study from the University of North Dakota. North Dakota Quarterly 85: 208-217.

Cvetkovich, Ann. 2012. Depression: A Public Feeling. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Davis, R.P. Stephen, Patricia M. Samford, Elizabeth A. Jones. 2010. The Eagle and the Poor House. In Beneath the Ivory Tower: The Archaeology of Academia. Edited by Russell K. Skowronek and Kenneth E. Lewis. 141-163. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida.

Dorn, Charles. 2017. For the Common Good: A New History of Higher Education in America. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Fabricant, Michael and Stephen Brier. 2016. Austerity Blues: Fighting for the Soul of Public Higher Education. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Gerstel, Sharon, Chris Kyriakakis, Konstantinos T. Raptis, Spyridon Antonopoulos and James Donahue. 2018. Soundscapes of Byzantium: The Acheiropoietos Basilica and the Cathedral of Hagia Sophia in Thessaloniki. Hesperia 87: 177–213. https://doi.org/10.2972/hesperia.87.1.0177

Henry, George. 1948. A Good Investment: the Story of Wesley College and that of the Mother Institution-Red River Valley University-- as well as the Story of Still Earlier Plans of the Methodist Church to Promote Educational Work of College Rank in North Dakota. Unpublished Manuscript. University of North Dakota Department of Special Collections. Chester Fritz Library. University of North Dakota. Grand Forks, ND. https://commons.und.edu/und-books/21/

Holtorf, Cornelius and Troels Myrup Kristensen. 2015. Heritage erasure: rethinking ‘protection’ and ‘preservation.’ International Journal of Heritage Studies. 21:4: 313-317, DOI: 10.1080/13527258.2014.982687

Holtorf, Cornelius. 2018. Embracing change: how cultural resilience is increased through cultural heritage. World Archaeology 50.4: 639-650. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2018.1510340

Labaree, David. 2017. A Perfect Mess: The Unlikely Ascendancy of American Higher Education. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Liming, Shelia. 2019. My University is Dying. The Chronicle of Higher Education. 25 September 2019. https://www.chronicle.com/interactives/20190925-my-university-is-dying

Murray, Simon. 2020. Performing Ruins. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Newfield, Christopher. 2017. The Great Mistake: How We Wrecked Public Universities and How We Can Fix Them. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Papalexandrou, Amy. 2017. Perceptions of Sound and Sonic Environments across the Byzantine Acoustic Horizon. In Knowing Bodies, Passionate Souls: Sense Perceptions in Byzantium. Edited by Susan Ashbrook Harvey and Margaret Mullett. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection. 67-86.

Perry, Sara. 2019. The Enchantment of the Archaeological Record. European Journal of Archaeology, 22(3), 354-371. doi:10.1017/eaa.2019.24

Robertson, Edward P. 1935. The story of the affiliation of Wesley College with the University of North Dakota. Unpublished Manuscript. University of North Dakota Department of Special Collections. Chester Fritz Library. University of North Dakota. Grand Forks, ND.

Robinson, Elwyn. 1975. The Starcher Years. North Dakota Quarterly. 39.2.

Skowronek, Russell K. and Kenneth E. Lewis, eds. 2010. Beneath the Ivory Tower: The Archaeology of Academia. Gainesville, Florida: University Press of Florida.

Staley, David J. 2019. Alternative Universities: Speculative Design for Innovation in Higher Education. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Tringham, Ruth. 2019. Giving Voices (Without Words) to Prehistoric People: Glimpses into an Archaeologist's Imagination. European Journal of Archaeology. 22.3: 338-353. doi:10.1017/eaa.2019.20/

Turner, Victor. 1969. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. New Brunswick ; London : Aldine Transaction

Turner Victor and Edith Turner. 1978. Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture. New York: Columbia University Press.

van Gennep, Arnold. 1909. Les rites de passage. Paris: Émile Nourry.

Wilkie, Laurie. 2010. The Lost Boys of Zeta Psi: A Historical Archaeology of Masculinity at a University Fraternity

Yanni, Carla. 2019. Living on Campus: An Architectural History of the American Dormitory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.