What To Do When The Dead Linger

Exploring Hauntedness as a Material Property of Objects

Citation: Hanson, Rosemary. 2021. "What To Do When the Dead Linger: Exploring Hauntedness as a Material Property of Object". Epoiesen. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.22215/epoiesen/2021.10

Rosemary Hanson is a freelance archeological illustrator and 3D modeler (rosemary.m.hanson@gmail.com) ORCID: 0000-0002-4371-4981

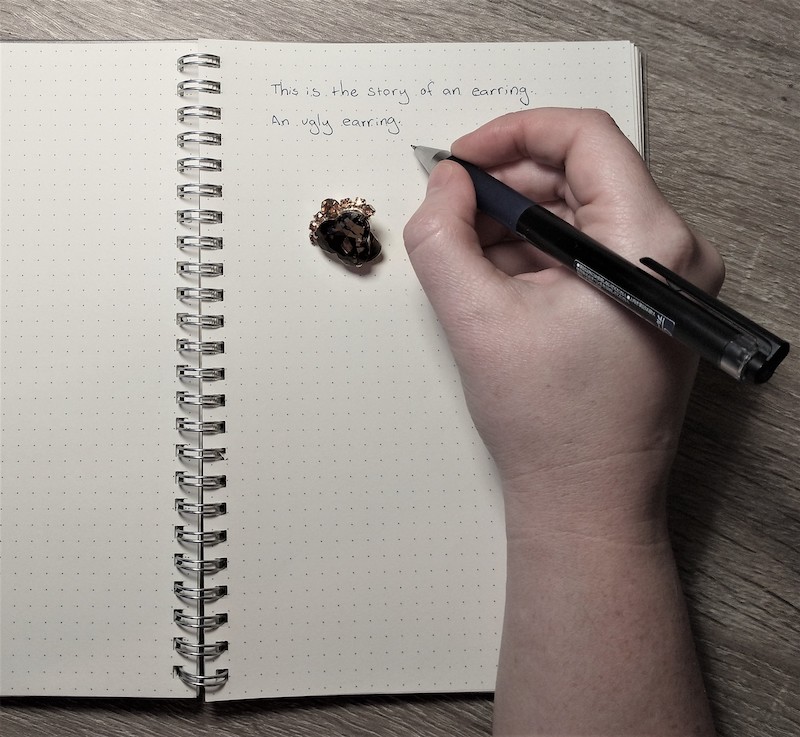

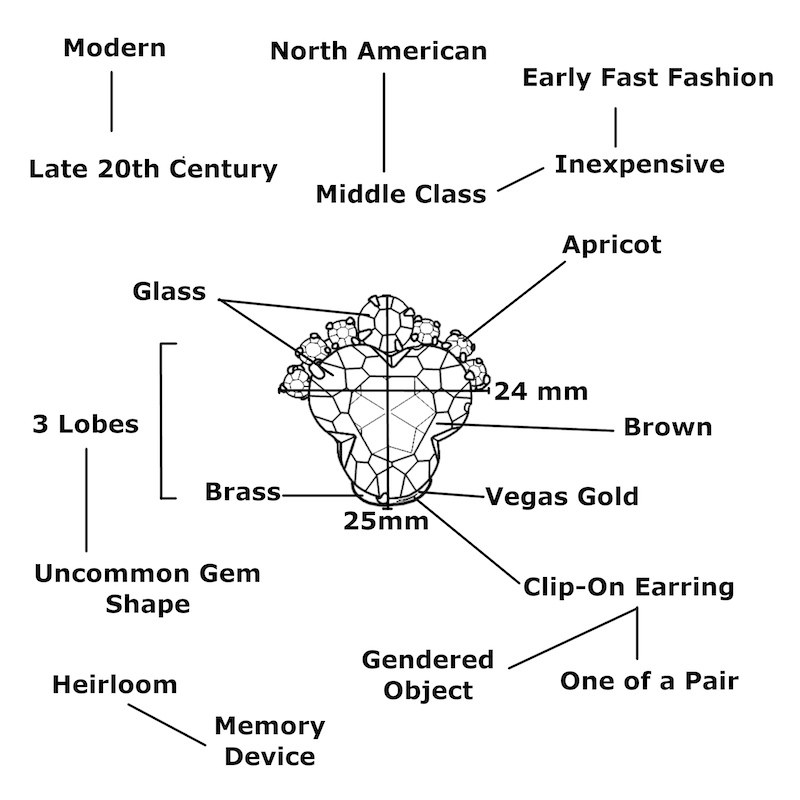

An ugly earring.

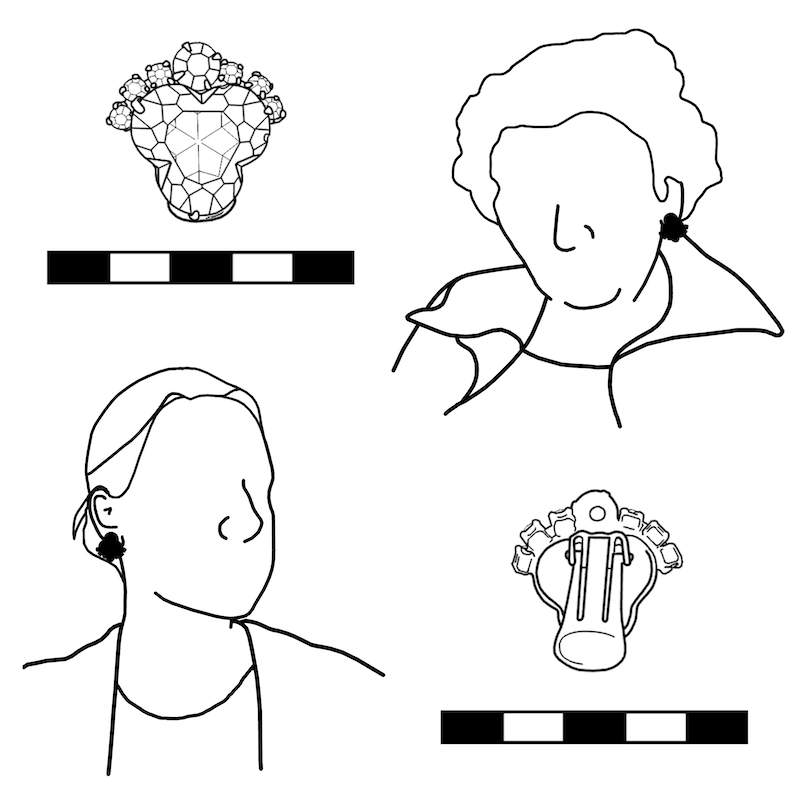

Cheaply made and cheaply bought, it is meant to resemble a queenly diamond in glass and brass. A large, 3 lobed brown jewel sits beneath a crown of small, round, apricot-colored gems in a color palette that now seems a stereotype of the 1970s. These faux diamonds have been haphazardly set into a thin, metal clip that pinches and weighs the ear unpleasantly. It was presumably once part of a pair, but its twin has long ago been lost in the back of a drawer or the case of a second-hand shop or (most likely) underneath 200ft of Tacoma landfill. It is, without doubt, an object out of place. I keep it in my jewelry box, but I have no intention of wearing it. It has no functionalist, aesthetic, or rational role in my life and there is really no reason that I should keep it.

Bea, somehow, has made this object different.

A framed photograph of Bea has been edited to include a halo, a motif from religious art used to denote sainthood. This saintly photograph posed with the earring is meant to evoke the small home shrines to Catholic Saints seen during the childhood of the author.

More than the Sum of Its Parts

Hauntedness as a Material Property of Objects

Hauntedness is therefore a subjective property of object materiality. It is a property in which the dead imbue matter with agency. This agency may be physical[11], magical[7][6][12], and/or emotional[13][14], but it is a power that emerges from biographical associations between people and things[1][15]. It is a persistence of entanglement between the dead, the living, and material objects in a panoply of configurations across time and space[13][3].In this sense, haunted objects are a prime example of mixtures[3] or bundles[16]. They are both subject and object, human and nonhuman, real and unreal, effected by and effecting human consciousness, and full of contradictions and bifurcations[3]. They make the social physical and the physical social[16], entangling, mixing, and distributing human consciousness and object materiality[17]. They compress and distort time and disrupt the neat separation of past, present, and future[13][18].

In failing to recognize these relational frameworks, my own experience of a haunted object simply does not exist.

Humanist Problems Require Creative Solutions

Indeed, attempts to measure and record evidence of ghosts and spirits quickly diverge into the realms of ghost hunting [11], spiritualism[21], and pseudo-archeology[26][27]. Instead, subjective questions require a more subjective toolkit: one that engages this subjectivity, as opposed to resisting or obscuring it[32]. This paper deploys two such tools to explore hauntedness as a material property of objects. The first is auto-ethnographic storytelling [11][13][14], and the second is visual artistic practice[33][13][32]. In doing so, I seek to demonstrate the ways that creative practice can be deployed to enrich more traditional forms of analysis.

Case Studies

I. Objects Possessed

Clearly, there is something in the experience of hauntedness that resists and endures.

II. Object Aura

Background image, this slide: In cultural heritage contexts, labels are a primary medium by which objects are denoted as special. Archeological labels and museum labels each tie an object into an object biographical framework - relating the entanglements that separate an ordinary object from an extraordinary object.

In cultural heritage contexts, labels are a primary medium by which objects are denoted as special [63]. Archeological labels and museum labels each tie an object into an object biographical framework - relating the entanglements that separate an ordinary object from an extraordinary object.

III. Objects of Memory

I want to remain haunted.

Conclusion

Background image: Objects cast long shadows, both literally and metephorically. These metephorical shadows may be far larger and more evocative than the objects themselves, and are vital to understanding the effects of materiality on our experiences of the world. To represent objects as purely objective packets of materials is to represent them without dimensionality.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Amy, for hunting down family photographs, to Bill and Marge, for their wonderful collection of images, to Shawn, for his unwavering enthusiasm, technical knowledge, and formatting prowess, and to Bea, who inspired it all.

References

[1] Holtorf, C. 2002. Notes on the Life History of a Pot Sherd. Journal of Material Culture. 7(1), pp.49-71.

[2] Ingold, T. 2007. Materials Against Materiality. Archaeological Dialogues. 14(1), pp.1-16.

[3] Webmoor, T. & Witmore, C. L. 2008. Things Are Us! A Commentary on Human/Things Relations under the Banner of a ‘Social’ Archaeology. Norwegian Archeological Review. 41(1), pp. 53-70.

[4] Gilchrist, R. 2013. The Materiality of Medieval Heirlooms: from Biographical to Sacred Objects. In: Hahn, H. P. and Weiss, H. eds. Mobility, Meaning and Transformations of Things: Shifting Contexts of Material Culture through Time and Space. Oxford: Oxbow Books. pp.170-182.

[5] Hamilakis, Y. & Jones, A. 2017. Archaeology and Assemblage. Cambridge Archaeology Journal. 27(1), pp. 77-84.

[6] Mukharji, P. B. 2018. Occulted Materialities. History and Technology. 34(1), pp. 31-40.

[7] Herva, V., Nordqvist, K., Herva, A. & Ikäheimo, J. 2010. Daughters of Magic: Esoteric Traditions, Relational Ontology and the Archaeology of the Post-Medieval Past. World Archeology. 42(4), pp. 609-621.

[8] Lucas, G. 2012. Understanding the Archaeological Record. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[9] Simandiraki-Grimshaw, A. 2012. Dusk at the Palace: Exploring Minoan Spiritualities. In: Roundtree, K., Morris, C. & Peatfield, A. A. D. eds. Archaeology of Spiritualities. New York: Springer. pp. 247-266.

[10] Benedetti, F. 2009. Placebo Effects: Understanding the Mechanisms in Health and Disease. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

[11] Baker, J. O., & Bader, C. D. 2014. A Social Anthropology of Ghosts in Twenty-First-Century America. Social Compass. 61(4), pp. 569-593.

[12] Zuanni, C. & Price, C. 2018. The Mystery of the “Spinning Statue” at Manchester Museum. The Journal of Objects, Art and Belief. (14), pp.235-251.

[13] Hill, L. 2013. Archaeologies and geographies of the post-industrial past: landscape, memory and the spectral. Cultural Geographies. 20(3), pp. 379-396.

[14] Ireland, T. & Lydon, J. 2016. Rethinking Materiality, Memory, and Identity. Public History Review. 23(16) pp. 1-8.

[15] Joy, J. 2009. Reinvigorating object biography: reproducing the drama of object lives. World Archaeology, 41(4), pp.540–556.

[16] Bauer, A. M. & Kosiba, S. 2016. How Things Act: An Archeology of Materials in Political Life. Journal of Social Archeology. 16(2), pp. 115-141.

[17] Hodder, I. 2011. Human-Thing Entanglement: Towards an Integrated Archaeological Perspective. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 17(1), pp.154-177.

[18] Supernant, K. 2020. From Haunted to Haunting: Métis Ghosts in the Past and Present. In: Surface-Evans, S., Garrison, A. E. & Supernant, K. Blurring Timescapes, Subverting Erasure: Remembering Ghosts on the Margins of History. New York: Berghahn. Pp. 85-104.

[19] Ingold, T. 2012. Toward an Ecology of Materials. The Annual Review of Anthropology. (41), pp.427-442.

[20] Young, C., & Light, D. 2012. Corpses, dead body politics and agency in human geography: following the corpse of Dr. Petru Groza. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographies. (38), pp. 135-148.

[21] Barber, M. 2016. Capturing the Invisible: OSG Crawford, Ghosts, and the Stonehenge Avenue. Bulletin of the History of Archeology. 26(1), pp.1- 23.

[22] Lamas, M. & Giménez-Cassina, E. 2012. Super Ghost Me: Stories from the ‘Other Side’ of the Museum. Museological Review. (16), pp. 77-92.

[23] Luscombe, A., Walby, K., & Piché, J. 2017. Haunting Encounters at Canadian Penal History Museums. In: Wilson et al. eds. The Palgrave Handbook of Prison Tourism. London: Palgrave Macmillan. Pp. 435-455.

[24] Burke, H., Arthure, S. & de Leiuen, C. 2015. A Context for Concealment: The Historical Archaeology of Folk Ritual and Superstition in Australia. International Journal of Historical Archeology. (20), pp. 45-72.

[25] Dowd, M. 2018. Bewitched by an Elf Dart: Fairy Archeology, Folk Magic, and Traditional Medicine in Ireland. Cambridge Archeological Journal. 28(3), pp.451-463.

[26] Bond, S. E. 2018. Pseudoarcheology and the Racism Behind Ancient Aliens. Retrieved 29 Sep 2021 from: Hyperallergic. https://hyperallergic.com/470795/pseudoarchaeology-and-the-racism-behind-ancient-aliens/

[27] Hiscock, P. 2012. Cinema, Supernatural Archaeology, and the Hidden Human Past. Numen. (59), pp. 156-177.

[28] Butler, B. 2016. The Efficacies of Heritage: Syndrome, Magics, and Possessional Acts. Public Archeology. 15(2-3), pp. 113-135.

[29] Harris, S. 2014. Sensible Dress: the Sight, Sound, Smell and Touch of Late Ertebølle Mesolithic Cloth Types. Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 24(1), pp.37-56.

[30] Harris, S. 2020. The Sensory Archaeology of Textiles. In: Skeates, R. & Day, J. eds. The Routledge Handbook of Sensory Archaeology. London: Routledge. Pp.210-232.

[31] Hurcombe, L. 2007. A Sense of Materials and Sensory Perception in Concepts of Materiality. World Archaeology. 39(4), pp.532-545.

[32] Watterson, A. 2015. Beyond Digital Dwelling: Re-thinking Interpretive Visualisation in Archaeology. Open Archaeology. (1), pp. 119–130.

[33] Glazier, D. 2005. A Different Way of Seeing? Toward a Visual Analysis of Archaeological Folklore. In: Smiles, S. & Moser, S. eds. Envisioning the Past: Archaeology and the Image. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. pp. 158-179.

[34] Kennedy, M. 2006. Forward: Souvenir. In: Russell ed. Images, Representations and Heritage. New York: Springer.

[35] Pétursdótter, Þ., 2012. Small Things Forgotten Now Included, or What Else Do Things Deserve? International Journal of Historical Archaeology. 16(1), pp. 577-603.

[36] James, S. 2011. Drawing Inferences: Visual Reconstructions in Theory and Practice. In: Molyneaux, B. ed. The Cultural Life of Images: Visual Representation in Archaeology. London: Routledge. Pp.22-47.

[37] Heath, S., Chapman, L., & The Morgan Centre of Sketchers. 2018. Observational Sketching as Method. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 21(6), pp. 713-728.

[38] Morgan, C. & Wright, H. 2018. Pencils and Pixels: Drawing and Digital Media in Archaeological Field Recording. Journal of Field Archaeology. 43(2), pp.136-151.

[39] Smiles, S. & Moser, S. 2005. Introduction: The Image in Question. In: Smiles, S. & Moser, S. eds. Envisioning the Past: Archaeology and the Image. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. Pp.1-12.

[40] Russell, I. 2006. Images of the Past: Archaeologies, Modernities, Crises and Poetics. Russell, I. ed. Images, Representations, and Heritage: Moving Beyond Modern Approaches to Archaeology. Dublin: Springer. pp. 1- 38.

[41] Perry, S. 2009. Fractured Media: Challenging the Dimensions of Archaeology’s Typical Visual Modes of Engagement. Archaeologies: Journal of the World Archaeological Congress. 5(3), pp.389-415.

[42] Smiles, S. 2005. Thomas Guest and Paul Nash in Wiltshire: Two Episodes in the Artistic Approach to British Antiquity. In Smiles, S & Moser, M. eds. New Interventions in Art History. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 133-157.

[43] Moluneaux, B. 2011. Introduction. In: Moluneaux, B. (ed.) The Cultural Life of Images: Visual Representation in Archaeology. London: Routledge. Pp. 1-10.

[44] Moser, S. 2014. Making Expert Knowledge through the Image: Connections Between Antiquarian and Early Modern Scientific Illustration. Isis. 105(1), pp.58-99.

[45] Yarrow, T. 2003. Artefactual Persons: The Relational Capacities of Persons and Things in the Practice of Excavation. Norwegian Archaeological Review. 36(1), pp. 65-73.

[46] Bateman, J. 2005. Wearing Juniho’s Shirt: Record and Negotiation in Excavation Photographs. In Smiles, S & Moser, M. eds. New Interventions in Art History. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. Pp.192-203.

[47] Warner, D. M. 1993. Caveat Spiritus: Jurisdictional Reflection Upon the Law of Haunted Houses and Ghosts. Valparaiso University Law Review. 28(1), 207-246.

[48] Luckhurst, R. 2012. Science Versus Rumour: Artefaction and Counter-Narrative in the Egyptian Rooms of the British Museum. History and Anthropology. 23(2), pp. 257-269.

[49] Stone, P. & Sharpley, R. 2008. Consuming Dark Tourism: A Thanatological Perspective. Annals of Tourism Research. 35(2), pp. 574-595.

[50] Hindmarch, J. Terras, M., & Robson, S. 2019. On Virtual Auras: The Cultural Heritage Object in the Age of 3D Digital Reproduction. In: Lewi, H., Smith, S., Cooke, S., vom Lehn, D. eds. The Routledge International Handbook of New Digital Practices in Galleries, Libraries, Archives, Museums and Heritage Sites. London: Routledge. Pp.243-256.

[51] Hampp, C. & Schwan, S. 2014. Perception and evaluation of authentic objects: findings from a visitor study, Museum Management and Curatorship, 29:4, 349-367.

[52] Cameron, F. 2007. Beyond the Cult of Replicant: Museums and Historical Digital Objects - Traditional Concerns, New Discourses. In: Cameron, F. & Kenderdine, S. eds. Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage: A Critical Discourse. Cambridge: MIT Press. Pp.1-21.

[53] McGraw, J. J., & Krátký. J. 2017. Ritual Ecology. Journal of Material Culture. 22(2), pp. 237–257.

[54] Gosden, C. & Marshall, Y. 1999. The cultural biography of objects. World Archaeology. 31(2), pp. 169-178.

[55] Nativ, A. 2014. Anthropocentricity and the Archaeological Record: Towards a Sociology of Things. Norwegian Archaeological Review. 47(2), pp.180-195.

[56] Denham, J. 2020. Collecting the Dead: Art, Antique and ‘Aura’ in Personal Collections of Murderabilia. Mortality. 25(3), pp. 332-347.

[57] Foster, S. & Curtis, N. 2016. The Thing about Replicas—Why Historic Replicas Matter. European Journal of Archaeology. 19(1), pp. 122-148.

[58] Gilks, P. 2016. The significance of celebrities’ personal possessions for image authentication: the Teresa Teng memorabilia museum. Celebrity Studies. 7(2), pp.221-233.

[59] Belk, R. W. 1988. Collectors and Collecting. Advances in Consumer Research. (15), pp. 548- 553.

[60] Cinque, T. & Redmond, S. 2019. The Fandom of David Bowie. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

[61] Cleaver, L. 2014 ‘Almost Every Miracle is Open to Carping’: Doubts, Relics, Reliquaries and Images of Saints in the Long 12th Century. Journal of the British Archaeological Association. 167(1), pp. 51-69.

[62] Gilchrist, R. 2008. Magic for the Dead? The Archeology of Magic in Later Medieval Burials. Medieval Archeology 52 (1), pp. 119-159.

[63] Berns, S. 2016. Considering the Glass Case: Material Encounters Between Museums, Visitors and Religious Objects. Journal of Material Culture. 21(2), pp.153-168.

[64] Gillings, M. 2005. The Real, the Virtually Real, and the Hyperreal: The Role of VR in Archaeology. In Smiles, S & Moser, M. eds. New Interventions in Art History. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 223-239.

[65] Walsh, P. 2007. Rise and Fall of the Post-Photographic Museum: Technology and the Transformation of Art. In: Cameron, F. & Kenderdine, S. eds. Theorizing Digital Cultural Heritage: A Critical Discourse. Cambridge: MIT Press. pp.1-13.

[66] Mills, R. 2016. Everyday Magic: Some Mysteries of the Mantlepiece. Public History Review. (23), pp. 74-88.

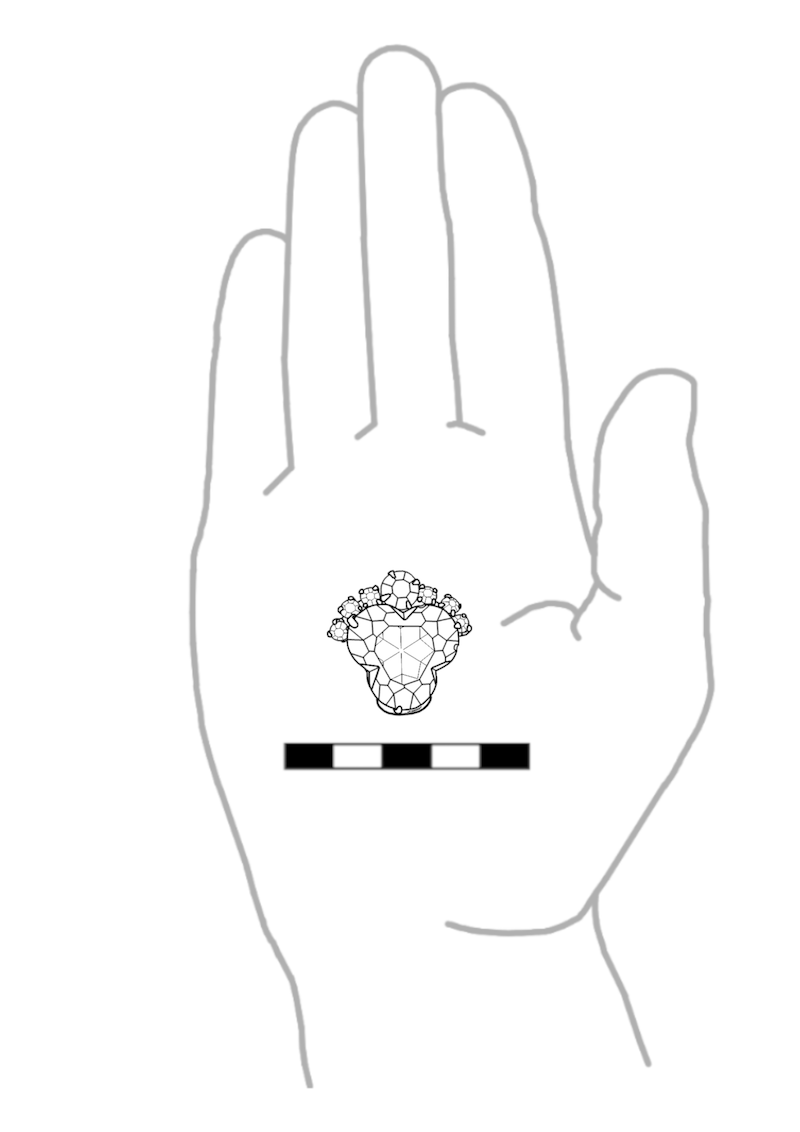

Image Production Notes

Fig 1. Photo taken on a Nikon D3100 and the image was edited in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Fig 2. Original photograph was digitized from the collection of Bill and Marge Richie using a smartphone camera. The digital photograph was then digitally edited into a frame owned by the author using the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

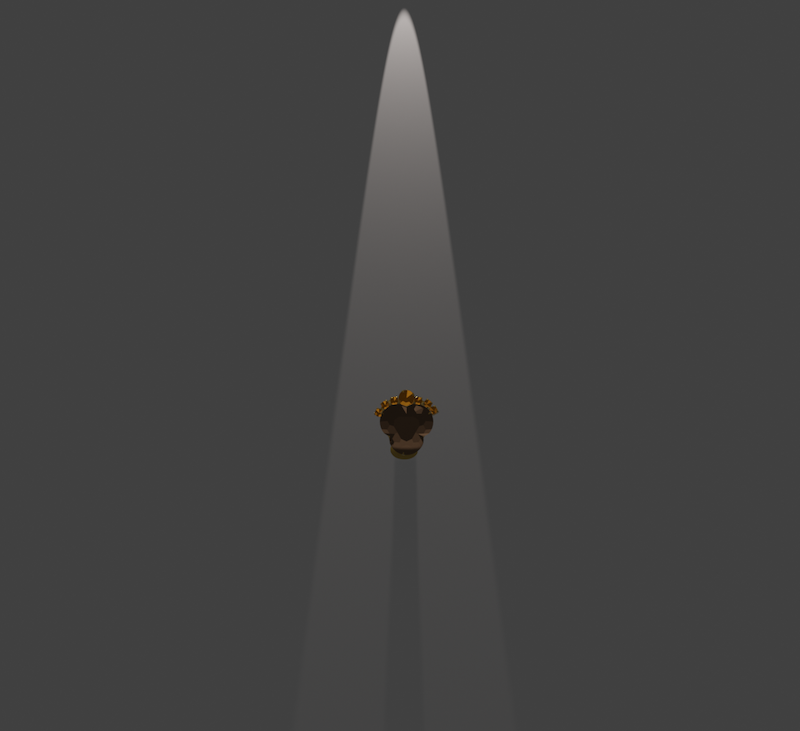

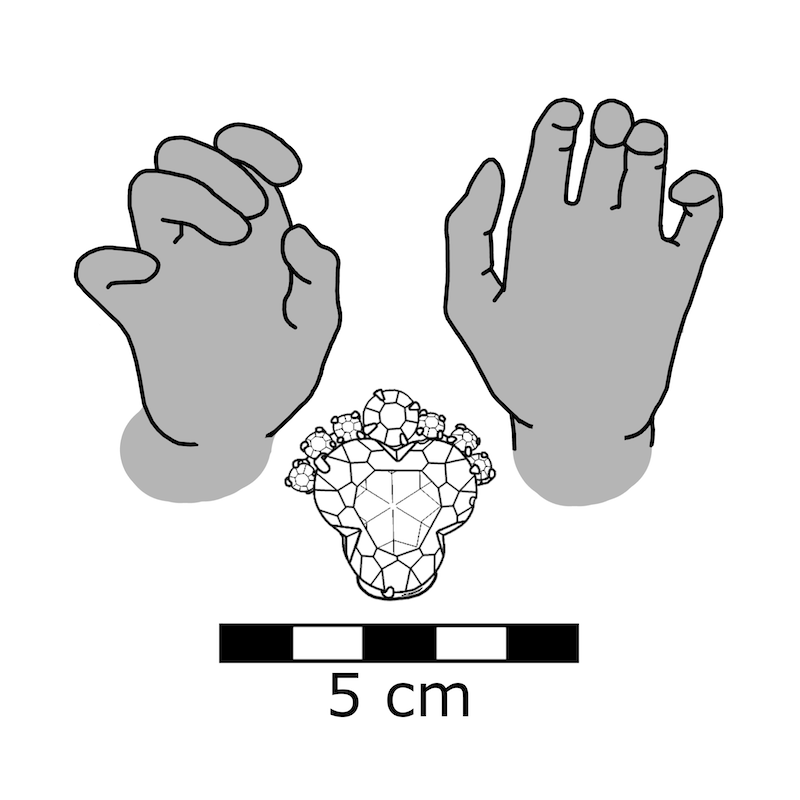

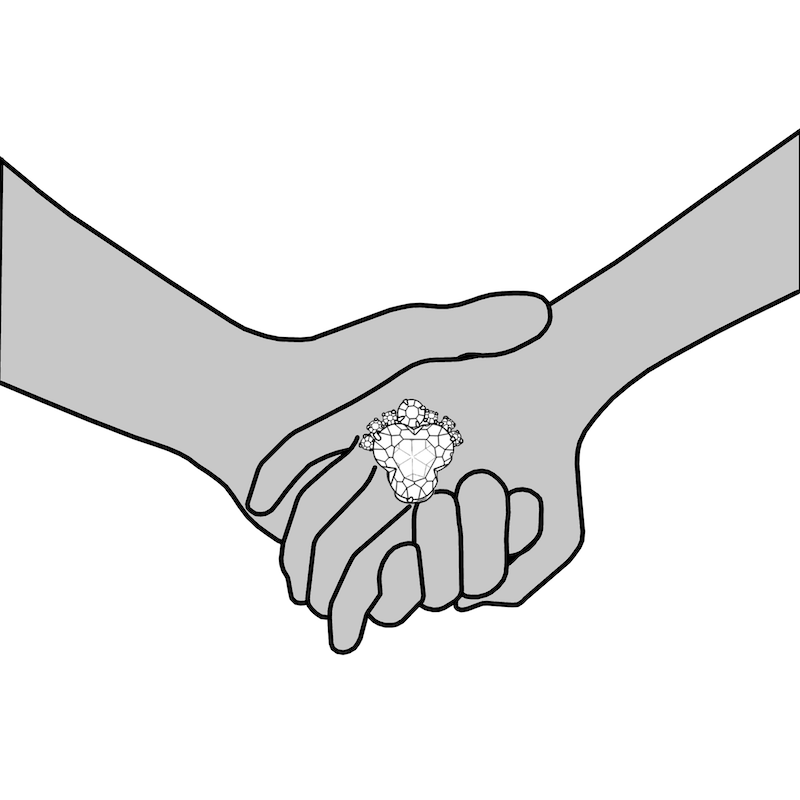

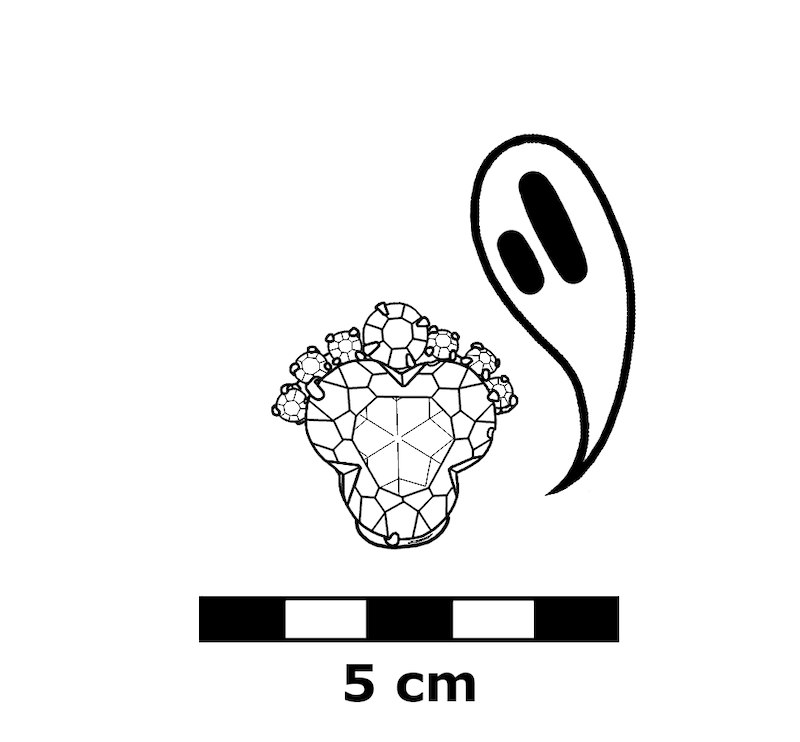

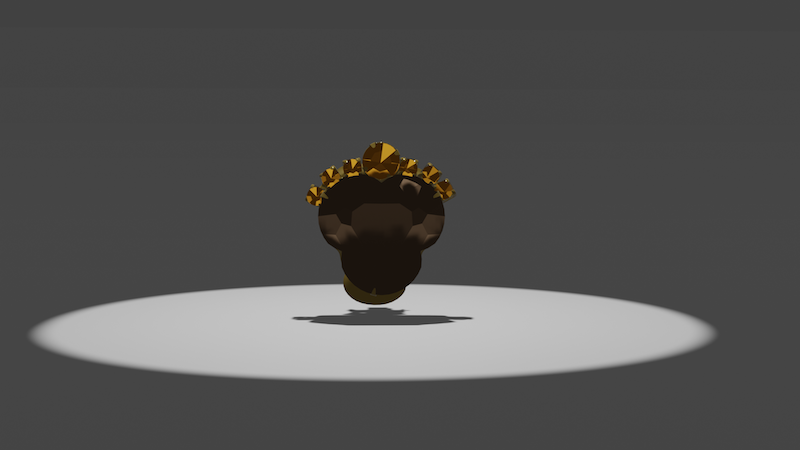

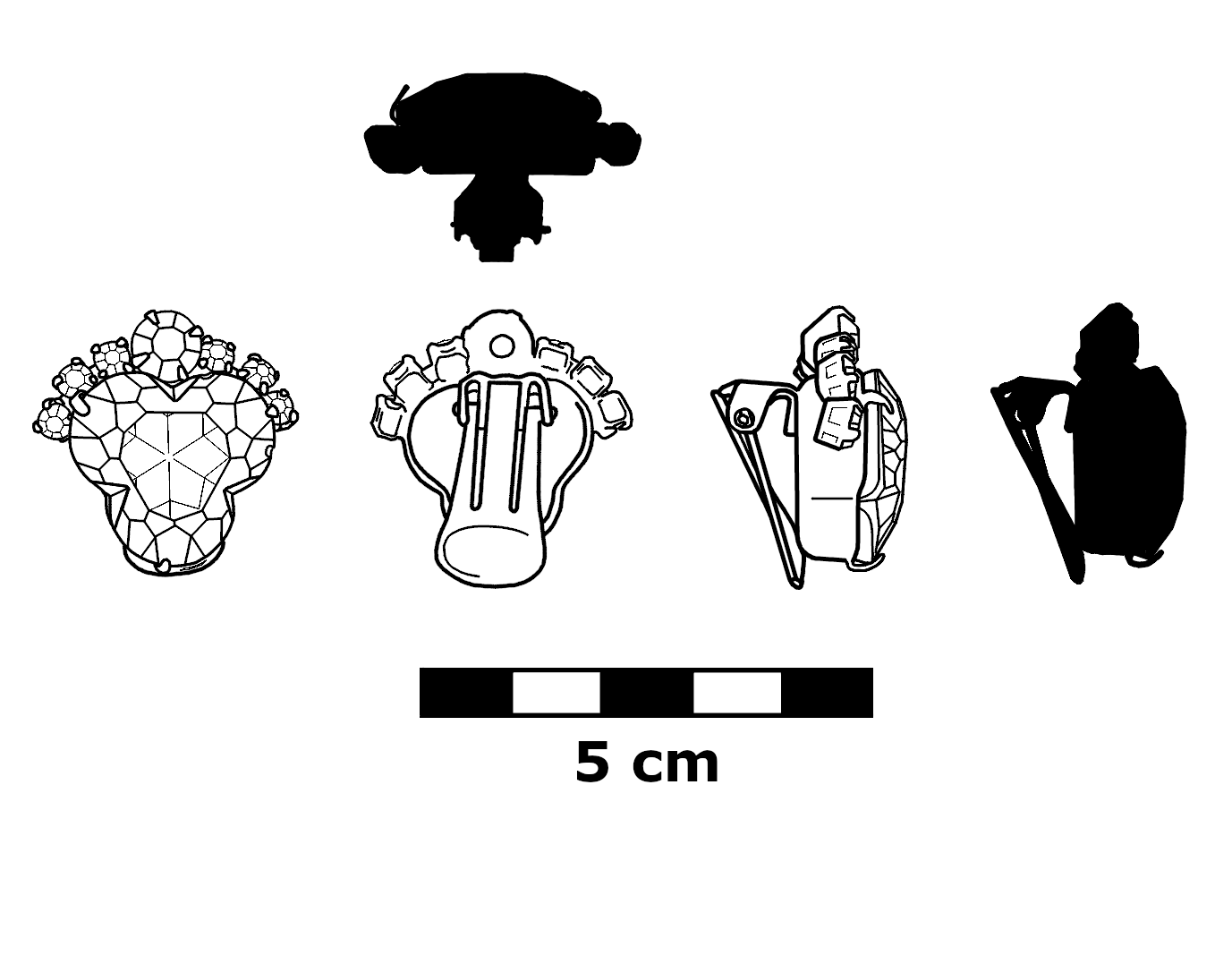

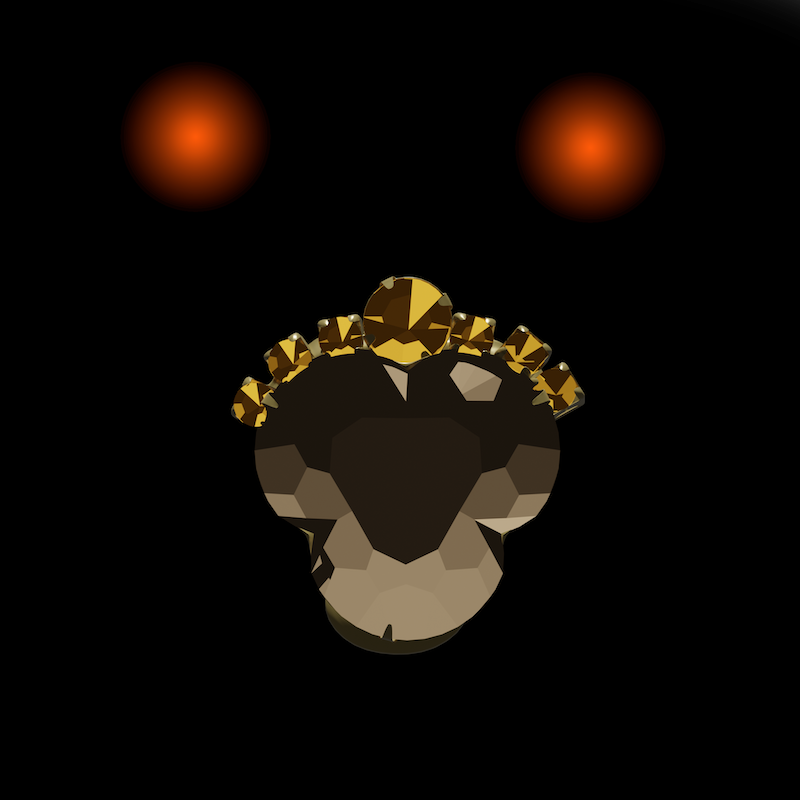

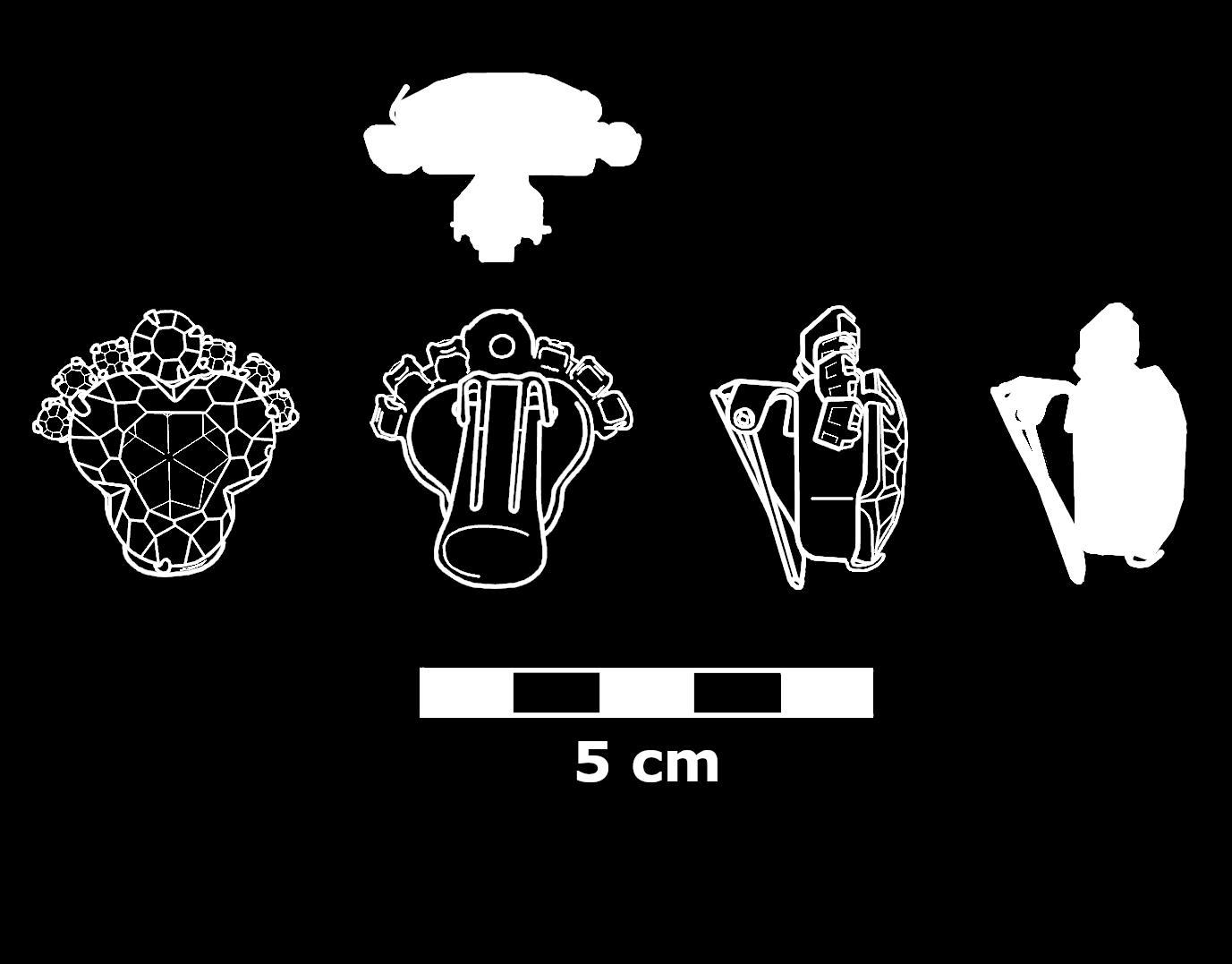

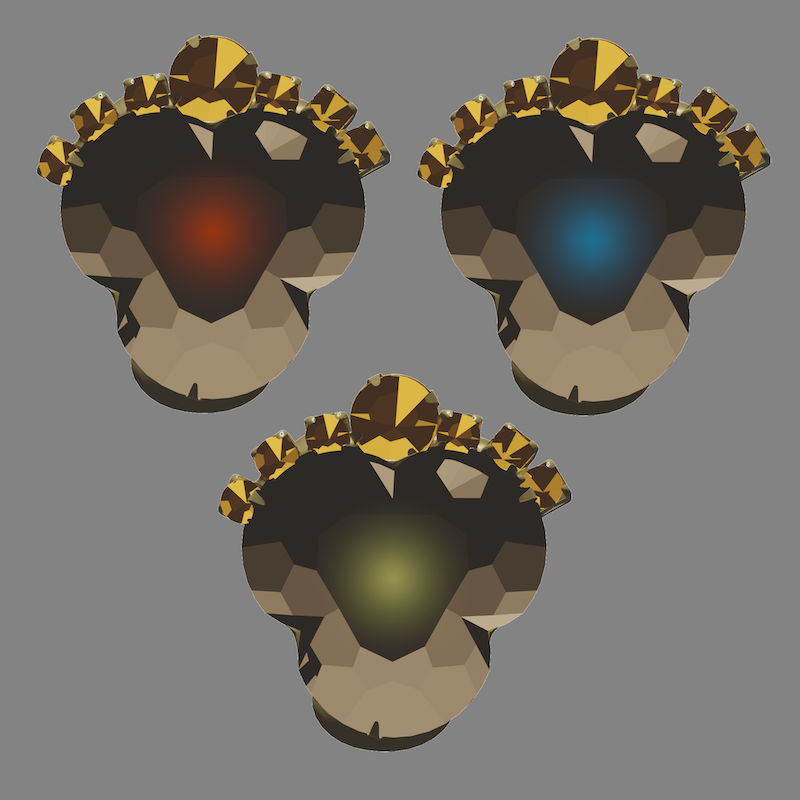

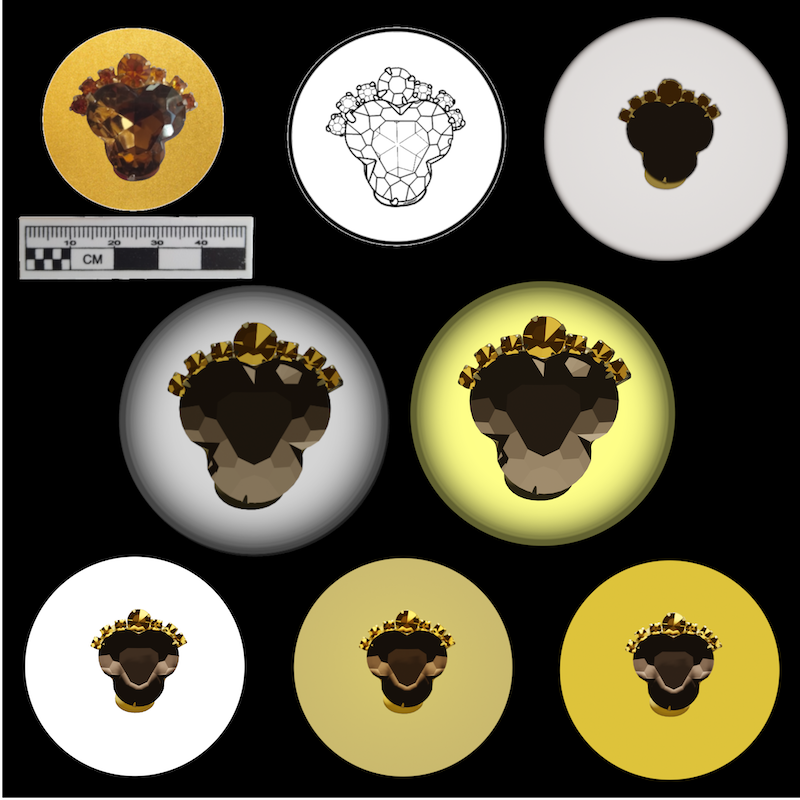

Fig 3. Model meshes were sculpted by hand using photographic references. Blender 2.93.5 was chosen after photogrammetric approaches failed due to the transparent, reflective materiality of the glass gems. Images were rendered using Eevee and then posed together using the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Fig 4. Screenshot of Blender 2.93.5 workspace during the process of editing the earring model mesh.

Fig 5. Digital 3D model of a clip-on earring, produced in Blender 2.93.5. This image was produced using a spotlight and a plane in addition to the earring mesh and was rendered using Eevee.

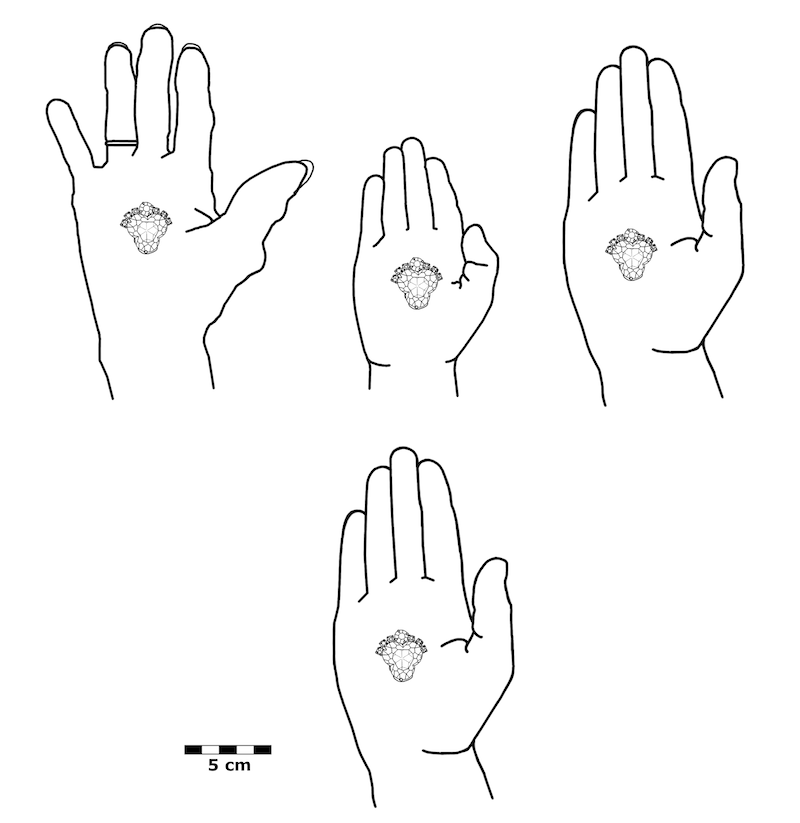

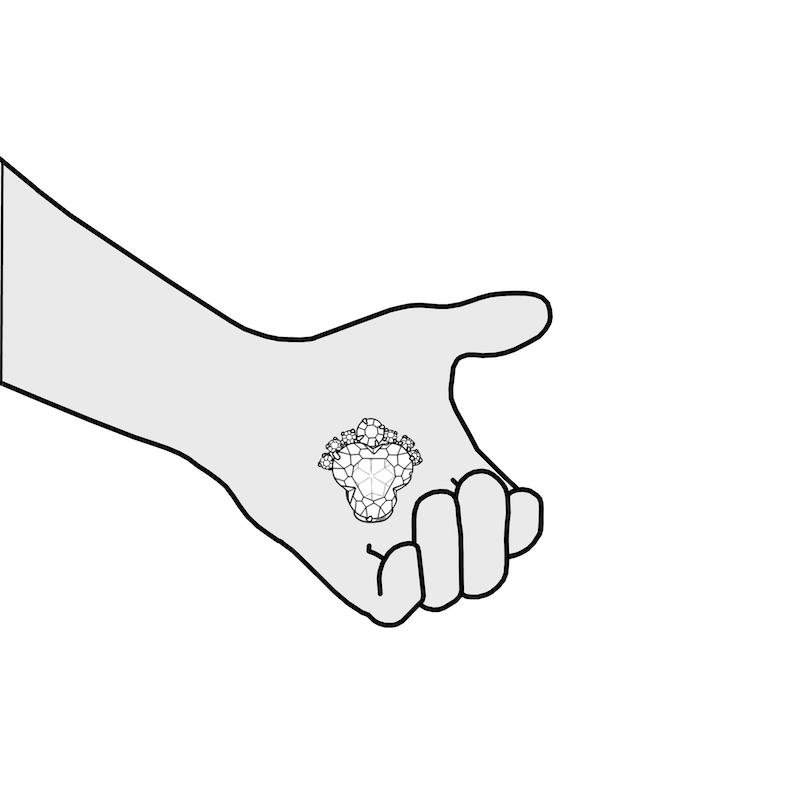

Fig 6. The earring illustration was produced in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22, using both a manually produced illustration and a photograph as references. Hands were then traced by the author in GIMP.

Fig 7. Images were taken from the personal collections of the author as well as the photographic collections of Bea's relatives, Bill and Marge Richie and Amy Hanson. They were then compiled in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Fig 8. Image was produced in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Fig 9. This image was produced using the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Fig 10. This image was produced in Blender 2.93.5 using a spotlight and a plane in addition to the earring mesh and was rendered using Eevee.

Fig 11. This image was produced using the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Fig 12. Photogrammetric data was compiled into a mesh in MeshLab and then exported to Blender. However, this resulted in a distorted mesh.

Fig 13. This photogrammetric data was produced from images taken on a Nikon D3100 Camera, compiled in Cloud Compare and exported to MeshLab.

Fig 14. Photogrammetric data was compiled into a mesh in MeshLab and then exported to Blender. However, this resulted in a distorted mesh.

Fig 15. Photograph taken with the camera from a Motorolla G8 Power smartphone.

Fig 16. Digital archeological illustration was produced in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22 from a digitized manual illustration and photographs of the artefact.

Fig 17. This image was produced using the 3D digital modelling software Blender 2.93.5. It was produced using a red-tinted spotlight and a plane in addition to the earring mesh and was rendered using Eevee.

Fig 18. This image was produced using the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22. The illustration was produced from manual illustrations and photographs.

Fig 19. This image was produced using the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22 from photographs of both the earring and the author’s hand.

Fig 20. The earring mesh was produced using the digital 3D modelling software Blender 2.93.5 and then rendered in Eevee. The image was then imported into the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22 and the halo was added.

Fig 21. The photograph of Bea was taken from the collection of Bill and Marge Richie, and then layered over a Blender 2.93.5 model of the earring in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Fig 22. The photograph of Bea was taken from the collection of Bill and Marge Richie, and then layered over a Blender 2.93.5 model of the earring in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Fig 23. The image was taken with the smartphone camera of a Motorolla G8 Power, and then edited with the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Fig 24. The modelled earring was produced in the digital 3D modelling software Blender 2.93.5, rendered with Eevee, and then layered over a background produced in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Fig 25. The modelled earring was produced in the digital 3D modelling software Blender 2.93.5, rendered with Eevee, and then layered over a background produced in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Fig 26. The modelled earring was produced in the digital 3D modelling software Blender 2.93.5, rendered with Eevee, and then layered over a background produced in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Fig 27. The modelled earring was produced in the digital 3D modelling software Blender 2.93.5, rendered with Eevee, then layered between backgrounds produced in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Fig 28. This illustration was produced in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Fig 29. The models were created and lit in the digital 3D modelling software Blender 2.93.5 and rendered with Eevee. They were then arranged against a black background in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Fig 30. The models were produced in the digital 3D modelling software Blender 2.93.5 and rendered in Eevee. Both inner glow and arrangement were them produced in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Fig 31. The modelled earrings in this image were produced and lit in the modelling software Blender 2.93.5 and rendered in Eevee. The photograph was taken with a Nikon D3100 Camera. Halos were produced variously in Blender and the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22. GIMP was also used to create the artefact illustration and background of the image.

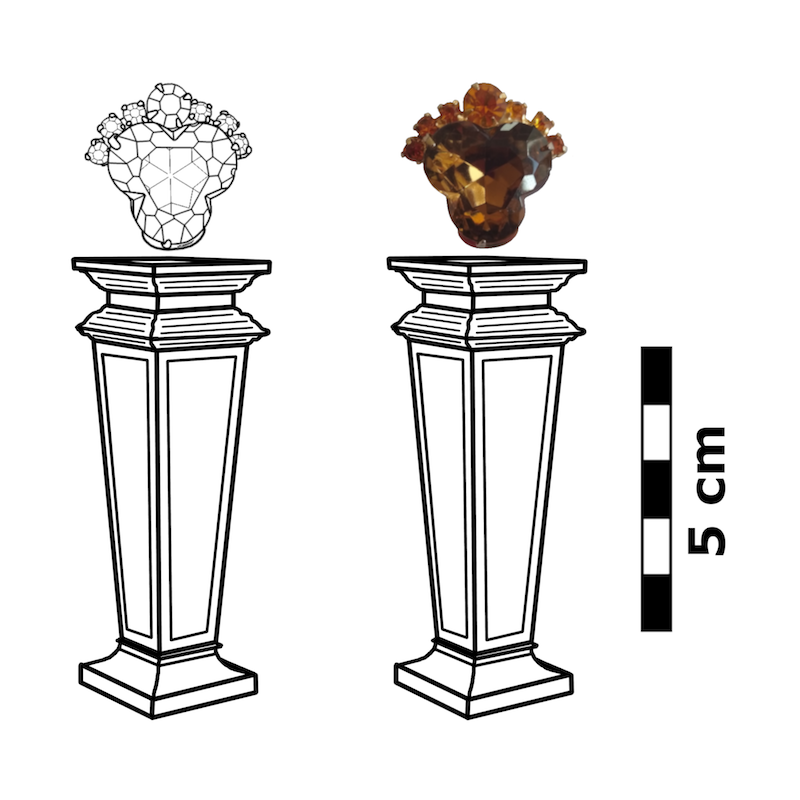

Fig 32. The photograph of the earring was taken on a Nikon D3100 Camera, and then edited into a sketch of both earring and pedestal produced in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Fig 33. This illustration was produced in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22 from photographs of both Bea and the author.

Fig 34. This illustration was produced in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22 from hand photographs.

Fig 35. Family photo from the collection of Bill and Marge Richie. Photo was digitized from the original using a smartphone camera.

Fig 36. This image was produced with the photo manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Background Image - photograph with halo - Original photograph was digitized from the collection of Bill and Marge Richie using a smartphone camera. The image file was then digitally edited in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22 along with images of the frame and earring taken using a smartphone camera from a Motorolla G8 Power.

Background Image - visual outline - This image was produced using the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Background Image - museum case - The modelled earring was produced in the digital 3D modelling software Blender 2.93.5, rendered with Eevee, and then layered over a background produced in the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Background Image - tagged object - This image was produced using the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22.

Background Image - Bea as part of the materiality of the earring - This image was produced from a 3D model produced in the digital 3D modelling software Blender 2.93.5 and rendered in Eevee. The model was then imported into the image manipulation software GIMP 2.10.22 where it was layered with a photograph of Bea from the collection of Bill and Marge Richie.

Background Image - object casting shadow - This image was produced and lit in the digital 3D modelling software Blender 2.93.5 and rendered in Eevee.