Discovering Oneself in the Study of History

History Is Not A Foreign Country

As historians – researchers, teachers, and students alike – we are often challenged to justify the value of our discipline. What’s the point of being stuck in the past, we are asked, when STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) subjects are the future of employment, funding, and indeed our very lives? The past is an immutable foreign country,[1] we are reminded, and we could better spend our time addressing the problems of the present than having our heads stuck in bygone times. Incessant lists of historic rulers, events, and battles recounted in dry academic papers seemingly offer little towards making our lives better today. And yet, such "lists" are only a miniscule part of the discipline and the apparent remoteness of the past is belied by our tendency to repeat history, rather than learn from it and "do better." More importantly, what if the concerns of the present time exist or have been exacerbated not only because of what transpired in the past but also because of our lack of knowledge, or lack of consideration, of that history? What if we can learn something about ourselves by studying history? Here, we bring together several seemingly disparate threads – pedagogical and personal – to show why history does matter and how presenting historical findings in novel ways can help us to heal the wounds of the past while rediscovering ourselves.

Unbordering Disease Histories

One of the biggest take-aways from the Diseases Without/Across Borders courses that I taught this past winter term at Carleton University and the University of Ottawa was that although pathogens and circumstances may change, human beings, as a whole, have tended to respond to epidemics and pandemics in much the same way across time and space. To varying degrees – and just like our recent experience with COVID-19 – historical pandemics, epidemics, and disease outbreaks were typically characterized by stigmatization, scapegoating, and divisiveness; by endless searches for explanations and the promotion of quack treatments; by isolation (self-administered or officially enforced), prevention mandates, and often violent protest. Having lived through their own recent pandemic, students remarked almost unanimously that they felt better equipped to connect to and understand (or at least empathize with) people’s experiences of disease in the past. In this case, incorporating discussion of the current pandemic allowed them to make more sense of pre-twenty-first-century ones, to see parallels and echoes of the present in historical anti-mask and anti-vaccination movements, in the othering and dismissal of victims, and in the push to "get back to normal" even when the danger was not yet over.

My courses focused on many of the big diseases in human history – tuberculosis, leprosy, plague, smallpox, syphilis, yellow fever, influenza, and so on – but for their final research projects, I gave students a lot of latitude. They could address any disease, any time period, and any geographical region that piqued their interest with only two criteria imposed. First, the disease in question had to cross some kind of border or boundary (geographic, socio-economic, cultural, racial, gender, and so on). Second, students had to anchor their projects to a key primary source that offered them a contemporary (and sometimes personal) point of entry into their topic (text, artwork, object, etc.). Pre-COVID, my courses included a field trip to Ottawa’s Canada Science and Technology Museum where students could enjoy a multi-sensory, interactive learning experience with disease-related artefacts. During the pandemic, I had to forgo the museum visit but was able to replace it with a hands-on learning unit generously curated and offered by Carleton’s Master Printer Larry Thompson about medical information production and dissemination; this allowed students to learn how to make and use quills and paper, to stitch handmade booklets, and to lay type on a printing press. Both approaches allowed students to discover the tangible aspect of history, to better sense what people in the past experienced – whether they were living with a disease, diagnosing and treating it, or writing information about it – and this in turn influenced how some of them approached their final research projects. Many also noted that, for the first time, they were seeing a new side to their studies: they gained a better appreciation of the many day-to-day objects that they hadn’t considered could relate to illness and disease and came to realize how objects related to disease, and to the production of information about disease, have changed so much over time.

The range of themes students selected this year was, as expected, broad, stretching all the way from the Plague of Athens (c.430 BCE) and the Justinianic Plague (c.541 CE) through leprosy in the Middle Ages to the portrayal of HIV/AIDS on Broadway in the 1980s and 90s and the role of public health agencies during the current COVID-19 pandemic. Between these temporal signposts, students addressed a variety of topics that included, among other things, nineteenth-century "Progressive Era" associations between immigrants and disease (alongside efforts to control and prevent both); infectious diseases in times of war; fashionability of disease (notably tuberculosis in the Victorian era); the management of and protests related to specific disease outbreaks (especially cholera in the 1800s and influenza in 1918–20); the imperialistic politics and economics of corporate/philanthropic disease mitigation strategies in developing countries; mythological and ritualistic representations of disease and treatment strategies; the intertwined nature of Victorian colonial poor relief and vaccination policies; and culturally appropriate explorations of malaria in colonial Africa. Geographically, the projects extended from Canada and the United States to Britain, Ireland, France, Russia, Greece, Byzantium (modern-day Istanbul), Egypt, Guatemala, Latin America, South Africa, "tropical" Africa, and Japan.

Students also creatively selected a variety of primary sources on which to build their projects, including theatrical productions, disease prevention and instruction manuals, medical treatises, newspaper and magazine articles, personal letters, accounts, and diaries, artwork (paintings, woodcuts, and manuscript illuminations), posters and pamphlets, novels, and maps. In previous iterations of this and similar courses, students have also used such varied primary sources as structures (both still standing buildings and architectural remains), tomb effigies and transi tombs, property boundary markers, photographs, astrological Zodiac Men and volvelles, religious banners (gonfalone), and medical prostheses.

Finally, in an effort to get them thinking seriously about how to modernize their final presentation of historical topics in ways that would better appeal to the audiences of today, I encouraged the students to submit their project results in non-conventional ways. It was, in part, the experiential learning exercises in the museum that first inspired me to promote non-traditional projects. Students could, of course, write a traditional history essay if that format was more comfortable and better suited to their topic. Many, though, chose to take a different route and offered podcasts (with or without accompanying sound effects and video), digital museum exhibits, storymaps, and websites, fictional short stories, innovative artwork (paintings, collages), graphic novels, and hand-stitched propaganda pamphlets. Their creativity was outstanding and inspiring. Most commented in their accompanying self-assessment that although producing an original project was more time consuming than writing a traditional essay, and sometimes came with a huge learning curve, they believed that they not only got more personal satisfaction from their research but also believed that their final product better conveyed the emotional and intangible aspects of their research and the issues they had examined.

For Augatnaaq, however, the final research project went much further than that: it unexpectedly turned into an at times difficult journey of historical self-discovery that unearthed long-suppressed memories and traumas of her community and of her own family. Her story follows, as does a link to the unique results of her final research project: a hand-sewn parka made from scratch using traditional crafting methods and themes to commemorate Inuit experiences in tuberculosis sanatoriums.

Recrafting Historical Memories

When I started this project, I knew I wanted to focus on tuberculosis sanatoriums and their effects on Inuit communities. From the 1940s to the 1960s, Inuit who were diagnosed with tuberculosis were sent away to tuberculosis sanatoriums in southern Canada in an attempt to combat the disease, which had been prevalent in the Arctic since the 1920s. In the Baffin or Qikiqtaaluk region, Nunavik, and Southampton Island (now known as Salliq or Coral Harbour) Inuit were tested for tuberculosis on the coastguard ships C.D Howe and the Nascopie.[2] If Inuit tested positive for the disease, they were kept aboard and sent to a southern sanatorium, and were not given the chance to say goodbye to their loved ones or to pack any belongings.[3] The forced journey of patients to southern sanatoriums was thus abrupt and traumatic; many unilingual Inuit were unsure of where they were going, why they were being forced to leave their homes, families, and friends, or even how long they would be gone. Most Inuit patients remained in the sanatoriums for two and a half years, but some stayed for six years; others never made it home again. The long stays at the sanitariums had devastating consequences on Inuit, both those in the sanatoriums and those left behind. Patients were isolated for nearly their entire stay, often unable to understand the nurses and doctors or communicate their own needs. Most were severely homesick and often hungry when the sanatorium provided insufficient meals. There also are countless stories of severe abuse in some of the sanatoriums.

The families of patients also faced negative implications that are still felt in the North today. Traditionally, Inuit women would sew clothing for their families while also taking care of the children while the men were out hunting for days or weeks at a time to provide food. Everyone had a role to play; when the mother or wife was sent south, there was no one to mend or make new clothing, which was (and is) crucial in the Arctic where temperatures regularly reach minus forty to fifty degrees centigrade in the winter. When the father or husband was away at the sanatorium, there was no one to catch animals used for food and whose skins were used for clothing. In Inuit culture, family is everything; family is essential for survival. Inuit are close with even their most distant cousins, and to have an integral family member abruptly removed was a devastating blow.

I had first learned about tuberculosis sanatoriums during my previous studies at Nunavut Sivuniksavut (an Inuit studies college program for Inuit beneficiaries). It was during this period that I first learned that my anaanatsiaq (grandmother), one of my aunts, and an uncle had all been sent away to a sanatorium in Manitoba. For my final project in the Diseases Without Borders course, I decided to dive deeper into this history by going through letters written by Inuit patients that were sent to the Department of Northern Affairs’ Eskimology division and recorded in the Eskimo Correspondence Records of Library and Archives Canada (LAC). I obtained access to these letters through the Aboriginal People’s Television Network (APTN) and LAC.

What I did not expect to find while going through these records were letters written by my own family members. It was through these letters that I learned first hand about the devastating consequences sanatoriums had on Inuit families, including my own. I discussed these unearthed letters with my family and found out that Inuit families were often forced to take in children whose mothers had been sent away for treatment, since their fathers had to hunt and work. This had been the case for some of my grandmother’s children. Two of my uncles, who were just babies when my grandmother was put in a sanatorium, were placed with another family until she returned more than two years later. I discovered through another letter that my grandmother’s younger half-sister had gone to live with their uncle Qusagat (written as koosherak) while both of my great-grandfather’s wives were in sanatoriums. Often, when mothers returned after being away for two to six years, their children had no memory or knowledge of them. In many cases, the children could not be returned to their biological parents because they were now strangers. My great-grandmother told my mother that once she returned to Arviat from the sanatorium, she knew she would never get her two sons back because after her five-year stay, they no longer knew who she was; they had adjusted to the family that they had lived with during the period she was away. Even when families were reunited, their bonds were forever altered and they remain estranged to this day. Another woman from my mother’s town had been sent to Winnipeg to deliver her child; while there, she was told she had tuberculosis and would have to enter a sanatorium. She was not allowed to take her child back to her family and instead she was forced to make the heartbreaking decision to put her child into foster care. Speaking with community members, I also discovered that many survivors who were unable to speak English ensured that their own children learned English (and sometimes only English), so that they would never have to endure what their parents had gone through.

It was not only parents who were affected by the sanatoriums; young children were also sent away for treatment. Many often forgot how to speak their native language after spending so many years in the south. Once they returned home, they found they could no longer communicate with their families. This left them ostracized and unsure of their identities. I had learned this while attending Nunavut Sivuniksavut when my friend’s father came in and told us about his four-year experience at a sanatorium when he was a child. To this day, many survivors have anxiety about travelling because it reminds them of their time spent in the sanatorium and the fear they had of never being able to see their families again. Mothers who were sent away at the same time as their children, such as my grandmother and two of her children, were separated for the duration of their stays, unable to see each other for two years despite being placed in the same sanatorium. Through my research I also found out that many children were strapped to their beds, unable to move, and often abused by the staff.[4] The horrific treatment faced by many patients not only scarred them for life but also affected their children and the generations after them, through intergenerational trauma and the ways some survivors unsuccessfully attempted to cope with that trauma.

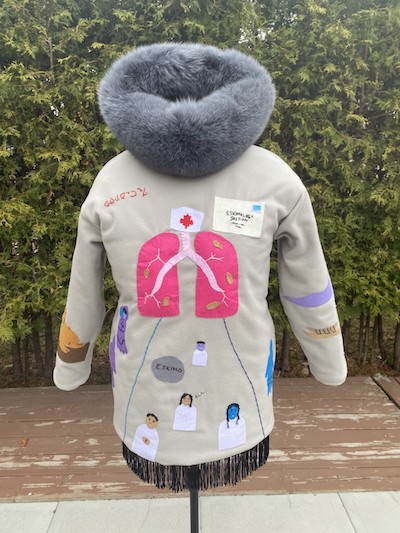

Image courtesy Augatnaaq Eccles, CC-BY-NC-SA.

I decided to represent my research and all that I had discovered about my community and family – and by extension about myself – by creating a parka using my anaanatsiaq’s pattern. This wasn’t just a simple parka, though: I also wanted to add designs using techniques common to Inuit wall hangings to represent the art that numerous Inuit patients created for sale to provide for themselves while they were at the sanatoriums.[5] The parka represents so many things. On the one hand, it reflects the colonial aspect of the sanatoriums that contributed to loss of language, low self-esteem, and the paternalistic role of the government and sanatorium workers towards Inuit. On the other hand, it is a symbol of resilience, of community, and of family.

This link showcases my final research project for the Diseases Without Borders course. It explains the processes through which I designed and created the parka and describes the meaning behind each image and set of words that I sewed onto it.

While I learned so much through this project, it was also very difficult to read about and then discuss the hardships that Inuit went through: their loss of family; starvation, not only of Inuit at sanatoriums but also their families back home who no longer had a hunter or provider; and the frequent mentions of abuse. At the same time, though, this project also gave me an entirely new understanding not only of my own family’s dynamics, but also that of my wider community and of all Inuit across Inuit Nunangat who were affected in one way or another by tuberculosis sanatoriums. Unlike for most courses, my project did not end with the submission of my parka and self-assessment. I have been motivated by this project to do everything I can to accurately and respectfully share this period of history, of my history, to represent the survivors and their families.

Revalorizing History as a Personal Voyage of Discovery

Not every piece of historical research will have same degree of personal connection that Augatnaaq’s did, and not every history project will inspire the creation of such a personal memorial. But history is about people; people who lived in the past, yes, but people whose lives and experiences very often still reverberate today. Finding those people and learning about them, their experiences – their joys, sorrows, and heartaches – and the material remains of their presence is about much more than just creating a family tree and participating in the popular Ancestry.com trend. The past directly contributes to what occurs today, to how we see our world and live in it. As Augatnaaq learned, some of the present-day family and community dynamics across Canada’s North that she has personally witnessed were the direct result of Inuit being sent away to southern tuberculosis sanatoriums. Language loss, anxieties about children leaving, and ongoing family estrangement are all present-day mirrors of what transpired in the past. And yet, as Augatnaaq admits, without having chosen to study this particular topic for her history course project, she never would have known any of it. She notes,

"I think for a lot of families there are things that people do that don’t seem to make sense, but once you understand the history of it you begin to see how at one point, or under a certain context, that fear or that action makes sense. For example, my mom was always extremely stressed just before my sister and I left for university or went to a medical appointment, and it never made sense until I understood it from her perspective, having gone to residential school and her family’s long historical association with the tuberculosis sanatoriums."

Things are rarely the way they are for no reason. We do the things we do because of some influencing factor from the past. We often unknowingly pass our experience down through generations. It is by gaining historical knowledge that we can begin to make intentional changes to do things better or differently. Studying history is important, because it allows us to find out why we do the things we do, to better understand our society and ourselves. And if we can get there by creating something unique that allows us to pass on what we learned in a way that speaks to and touches other people, so much the better. Historical pedagogy is not about lists of long dead rulers and conquerors; it is about providing the space for students to discover something about themselves, to be creative in expressing what they have learned, and sometimes, like Augatnaaq had done in this recent CBC news story, spreading the word that history has value for today.

L.P. Hartley, The Go-Between (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1953); David Lowenthal, The Past is a Foreign Country (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985). ↩︎

Pat Sandiford Grygier, A Long Way from Home: The Tuberculosis Epidemic Among the Inuit (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1994), 87. ↩︎

Ibid., 97. ↩︎

See, for example, Rob McKinley, "More Canadian Genocide: TB Sanitariums Rumours Of Abuse, Cover-Up At Clinics," [Windspeaker News](sisis.nativeweb.org/clark/sep98can.html) (September 1998), 44. ↩︎

See, for example, Frank Croft, "[The Changeling Eskimos of Mountain San](https://archive.macleans.ca/article/1958/2/1/the-changeling-eskimos-of-the-mountain-san)," Maclean’s, February 1, 1958 (which approaches the topic from a settler perspective). Numerous letters in the Eskimo Correspondence Record refer to Inuit sanatorium patients being paid (or requesting payment for) for sewing, carving, and other handicraft work. ↩︎