Ancient Egyptian Curses and Bog Bodies: First Response

Currently, I don’t do tumblr. However, Verstraete makes a compelling case for it as a dynamic social media platform with great potential to engage with public archaeology, pop culture, and help to dismantle pseudoarchaeology. Before its demise (Dennis 2023a, 2023b), I was a Twitter archaeologist and occasionally felt like an old whenever tumblr came up. However, a number of the meme-able moments explored by Verstraete extended out of tumblr into my non-tumblr social media and I loved the way that the memes engaged meaningfully with multiple layers communities.

The mismanagement of Twitter, beginning in late 2022 and continuing to the present, lead to a revival of tumblr and Ancient Egyptian Curses and Bog Bodies: The Role of Pseudoarchaeology in Tumblr’s Subculture adeptly outlines how the platform engages with many of the faults of other social media platforms to thoughtfully engage archaeological publics. Particularly, the way that Verstraete highlighted how tumblr’s reblog function acts as a permanent yet plastic dialogue with archaeological knowledge. This does not exist on other social media platforms and struck me as an important unique form of archaeological engagement.

Reblogging allows multiple users with various kinds of knowledge and engagement mediums to collaborate and cultivate an informative archaeological narrative. In addition, it creates a pathway for a multivocal cacophony of these narratives. While Verstraete skillfully incorporates specific widely-known engagements in the piece, the use of these materials as reblogged specifically to her own tumblr page demonstrates how those narratives can also be re-cut or captured incrementally to teach specific narratives. It’s a kind of archaeological storytelling in it’s own right by allowing both non-archaeologists and archaeologists alike to tell stories.

In a tangible way (in as much as anything digital is... tangible) the reblog function allows people to follow archaeological narratives through multiple users and actors who all engage with the same material in their own ways. This feature also allows multiple modes of storytelling appropriate for different kinds of audiences. And Verstraete’s versions for many of her examples offer a step into the narrative, a gateway to explore the topics even more.

One example of this is the way that Verstraete explains and contextualizes the use of the "bredlik poem". As a non-tumblr user, who had only seen the form reposted in often shorter snippets on other social media, the layers of engagement with this kind of meme were awesome to behold. Through her work, I began to see the use of the bredlik on tumblr as archaeological in its own way. It breathes continued life into a form that was thought to be out of use for many years. It’s a meme that’s been picked up by different generations to reuse in their new creation.

Conceptually, it reminds me of how until recently archaeologists relied on a division of then/now or history/prehistory rather than acknowledge that what precedes us lives within us. It is like the ancient stone re-used in a "medieval hows". Or the collection of even older projectile points by descendant communities for re-use or just for the idea of keepsake. Beyond the reuse of an old (for the internet) form, bredlik are then incorporated specifically with archaeological content to drum up engagement with new archaeological discoveries and knowledge is just the icing on the cake. Or the "deadly cheese" on the bread.

I further love the way that Verstraete’s work demonstrates how deftly, easily, and accessible people are already making archaeology. Her work demonstrates collaborative archaeological practice in a way that many archaeological projects hope to achieve but never quite do. tumblr produces tangible results, crunchable data, and clear assessment outcomes by seeing and following how the public takes our knowledge through the use of the reblog, notes, and other features. Specifically, does the public head straight away from our knowledge or do they keep coming back to us for more.

My favorite examples of this are the extensions and the elaboration on the bog body themes and the ancient grilled cheese memes. While of course few archaeologists would eat that grilled cheese, I love how engagement with these layered discoveries illustrate that social media is a way that people engage with archaeological knowledge and make it fun. Tumblr is clearly a place where what we (archaeologists) know about people based on cultural material lives, breathes, and plays in a way that is hard to find in other mediums.

I hope that others who explore Verstraete’s great work in this piece consider how useful tumblr can be for correcting archaeological narratives, engaging with various archaeological publics in an ethical fashion, and incorporating various mediums. I hope that Verstraete continues this work to incorporate the additional visual cues that tumblr also uses and how those can benefit future and existing archaeological projects.

References

Dennis, Meghan. 2023a. 'So You Used to Do Data Collection on Twitter?'' The Alexandria Archive Institute, 5 Oct. 2023, https://alexandriaarchive.org/2023/10/05/so-you-used-to-do-data-collection-on-twitter/.

Dennis, Meghan. 2023b 'Birds, Mastodons, and Ethical Choices'. The Alexandria Archive Institute, 22 Feb. 2023, https://alexandriaarchive.org/2023/02/22/birds-mastodons-and-ethical-choices/.

Cover Image "Image taken from page 321 'A series of original Portraits and Caricature Etchings by J. Kay' 1877 British Library

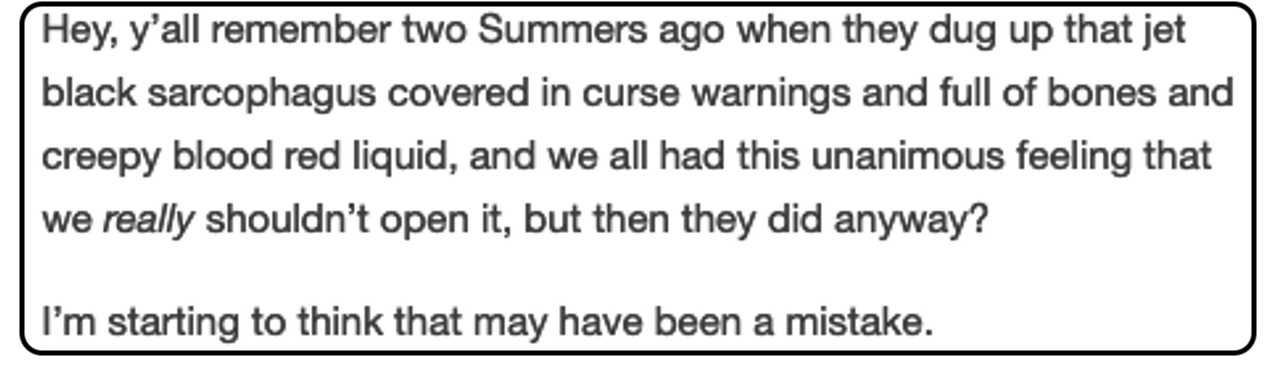

Mathead Image Screenshot by Emma Verstraete of meme posted to Tumblr