Material Culture and Popular Culture: Archaeological Adventures Outside the Ivory Tower

This journey began prior to the COVID-19 Pandemic upheaval and continued through it to a kind of other side. We found seeds for these scientific stories exploring the field’s appearance in popular culture in so many places. Some were at the last conferences before pandemic shut-downs, others in virtual conference presentations during the pandemic shut-downs, and yet more emerging from our social media networks, as online communities took on an increased importance as the pandemic carried (and carries) on. Having gathered the effort of so many people we are so excited to share this group of awesome archaeology articles because despite rocky ground, each flourished and found fertile soil here with the editors and contributors to this special issue for Epoiesen.

Archaeologists love popular culture. In one sense, it’s what we hope to understand about the past. Finding a ceramic pot used by thousands of people, because it was mass produced, says a lot more about our ancestors than one unique piece. In another sense though, archaeologists (the we in this) are humans who want to see ourselves represented. Seen doing our science, seen working with descendants and hopefully connecting them with their histories, and also just seen as people.

And that means all archaeologists. Just like representation in the field, popular culture is a lens into who the public sees as the stewards of archaeological knowledge, especially when we approach it from the perspectives of media made by non-archaeologists. Which all the pieces in this publication series discuss.

Beyond that, the various mediums of pop culture---digital, print, auditory, interactive, and/or visual---present an incredible avenue for telling stories, and archaeologists are incredibly adept storytellers. We may use science and hypothesis testing as part of our discipline but stories and storytelling play a key role in the everyday lives of people.

Stories are adaptive and can be fit into a multitude of scenarios that can help us make sense of the sometimes nonsensical world around us. Through these acts of sensemaking, stories act as a “social glue that brings the community together” (Bietti, Tilston, Bangerter 2018: 711).

For us, we define stories as something with a “narrative structure which . . . involves characters, events, and plotlines” (Praetzellis 2014: 5135). As Mark Pluciennik (1999: 635) notes, “archaeologies are presented in the form of narratives understood as sequential stories,” and the archaeological imagination found in the narratives of archaeology, as described by Michael Shanks (2020: 47), is a “key component of our experiences of the past.

Produced by the archaeological imagination, from every archaeological site stories emerge that are full of characters, events, and plot lines drawn together and interpreted into knowledge-building narratives. Archaeological narratives tell stories that are both about the site’s past (the people, places, belongings, and events archaeologists uncover) and about the process of making sense of that past (our process of interpreting what we uncover).

Importantly, archaeological stories offer a meaningful way to connect with and learn from the past. They also help “make the past accessible to the present,” (Praetzellis 2014: 5135) and can even connect the past to the future, through what Akin Ogundiran (2023) called a “pedagogy of renewal.” Writing about African heritage, Ogundiran (2023: 450) described how archaeology could contribute to a pedagogy of renewal with a goal to “provide learners with an education that does not alienate them from their tradition, culture, and history,” and instead “reinvigorates, restores, revives, and reaffirms African heritage, environment, epistemology, value systems, and ontology as the basis of inquiry, interpretation, and self-understanding.”

Archaeological stories, whether written for archaeologists ourselves such as the dual narrative presented in What this Awl Means: Feminist Archaeology at a Wahpeton Dakota Village (Spector 1993) or for the non-archaeological public such as in Exit Archaeology (Fawkes 2018), enable meaningful connections to the past by sharing knowledge in an inspiring, captivating, engaging manner that moves beyond objects and features to include the people and events behind them. They remind us that “[o]ur lives are storied” (Jackson 2006:245).

Beyond that, the story of the human past as told through material culture--one definition for archaeology---is only “everyone’s” when those stories are accessible and reflect the diversity of the human experience both past and present. This means sharing and engaging in archaeology beyond academic papers only read by “our peers” for review. It means having archaeologists from historically under-represented groups write archaeological narratives and stories. It means making those papers accessible to the public by publishing them without a paywall.

These components allow archaeological stories for the public to actually make it to the public. Because we don’t just study the lives of the rich, we study the lives of the people. We see this publication series as an aspect of archaeological stewardship. It ensures that archaeologists participate in public discussions to limit the voice that harmful, often pseudoarchaeological, narratives have in the public arena.

While archaeologists can guide these discussions, we don’t always need to take the mic. Instead this special issue acknowledges that it’s ok to let non-archaeologists tell the story. At least…sometimes.

The papers in this collection explore how the representation of archaeology in media created by non-archaeologists lacks intrinsic qualities of good or bad. Such qualities require definitions and, instead, should be considered in terms of effect and harm. In a world where the lines between fact and fiction can become dangerously blurred, it is important to consider how the representation of archaeology and pseudoarchaeology in pop culture impacts lived experience. Not just whether they get the archaeology right. Especially when archaeology and archaeologists themselves have caused harm in some communities (Colwell 2017).

This special issue acknowledges how bad representation of “the archaeology” doesn’t necessarily cause harm. From storylines based on pseudoarchaeology, which is getting something wrong intentionally for bad reasons, to looking at landscape archaeology in the worlds of Zelda, which gets things wrong but incorporates valuable critiques of the field, exploring these popular stories allows archaeologists to assess and understand how the public views our practice. Seeing such themes in popular culture provides a lens to view the ways archaeology historically upheld oppression in some communities (Colwell 2017) and also consider how our practice can dispel oppression.

We hope that this special issue, beginning with this introduction and continuing with a series of four papers and their responses, brings these discussions to archaeologists and non-archaeologists alike.

And our first paper, written by Dr. Emma Verstraete, does a fantastic job of this. "Ancient Egyptian Curses and Bog Bodies: The Role of Pseudoarchaeology in Tumblr’s Subculture" explores archaeologists’ interactions in modern popular culture. It explores how modern archaeologists use and share their expertise through the social media platform tumblr to engage with archaeological knowledge. Verstraete traces the utility of various memes to explore how archaeologists can accurately and amusingly share what we know in a more democratized fashion.

Following this is Paulina F. Przystupa’s article considering the representation of Black archaeologists in comic books written by non-archaeologists. The piece considers how comic books portray archaeologists in fictional settings. Przystupa focuses on how non-archaeologist comic creators are good at representation by including Black archaeologists. Yet, they inadvertently cause harm by writing stories that undercut those Black archaeologists’ expertise or by portraying white archaeologists causing harm to Black archaeologists without serious repercussions.

Transitioning even farther into fiction, Dr. Alex Fitzpatrick’s "Side Quest Added: Video Game Mechanics and the Potential for Pseudoarchaeology" also considers how archaeology in fiction has implications for causing harm in the real world. Dr. Fitzpatrick explores the mechanic of the side quest in video games and its interaction with archaeology. The ethical implications of the behaviors in the games Dr. Fitzpatrick explores provide interesting contrasts and demonstrate a consistent thread of archaeology as a subtext in games across various genres.

From there, we sail to Hyrule where Dr. Emily Van Alst and Dr. Mackenzie Cory explore the construction of archaeology within a completely different world. Focusing exclusively on the archaeological themes of Legends of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, the first game in a series, the team explores how many themes of the game have an inherent archaeological basis. They deftly highlight how the subtle shift away from being a human with different skin to a completely different looking species allows popular culture to double down on the disenfranchisement of Indigenous people.

These works transition from archaeologists as storytellers, to storytellers exploring archaeologists, to storytelling as archaeology, to archaeology as storytelling. These provide a link to consider how archaeology is the study of pop culture and the stories we tell about it. Bog Bodies taking the wheel, Black archaeologists in comics, archaeology as sidequests, and Indigeneity in Zelda all illuminate how archaeology permeates communities outside our field. And not only our world, the material one we inhabit, but the ones that people choose to create in fiction or within online communities via the meme-o-sphere. These papers and their responses all highlight how no matter where you look, you can find a bit of archaeology.

References

Colwell, J, 2017 Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits: Inside the Fight to Reclaim Native America's Culture, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Lucas M. Bietti, Ottilie Tilston, Adrian Bangerter 2019, ‘Storytelling as Adaptive Collective Sensemaking’, Topics in Cognitive Science, vol. 11, pp. 710-732.

Akin Ogundiran 2023, 'Storytelling in Archaeology and a Quest for a Pedagogy of Renewal’, African Archaeological Review, vol. 40, pp. 447 - 453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-023-09553-6

Mark Pluciennik 1999, ‘Archaeological Narratives and Other Ways of Telling’, Current Anthropology, vol. 40 issue. 5, pp. 653-678.

Praetzellis, A. (2014), ‘Narrative and Storytelling for Archaeological Education’, in Claire Smith (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology. New York: Springer New York, pp. 5135-5138

Shanks, M (2020), ‘The Archaeological Imagination’, in Abraham, A. (Ed.) The Cambridge Handbook of the Imagination. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 47-63.

Spector, Janet 1993, What this Awl Means: Feminist Archaeology at a Wahpeton Dakota Village, Minnesota Historical Society Press, St. Paul.

Fawkes, Glynnis 2019, Exit Archaeology: A Season on a Dig in Greece, Glynnis Fawkes.

Jackson, M. 2006, The Politics of Storytelling: Violence, Transgression and Intersubjectivity, Critical Anthropology Series Vol. 3, Michael Jackson, series editor, Museum Tusculanum Press, Copenhagen.

Cover image "Babilonski stolp" , unknown painter, 17th Century. Maribor Regional Museum.

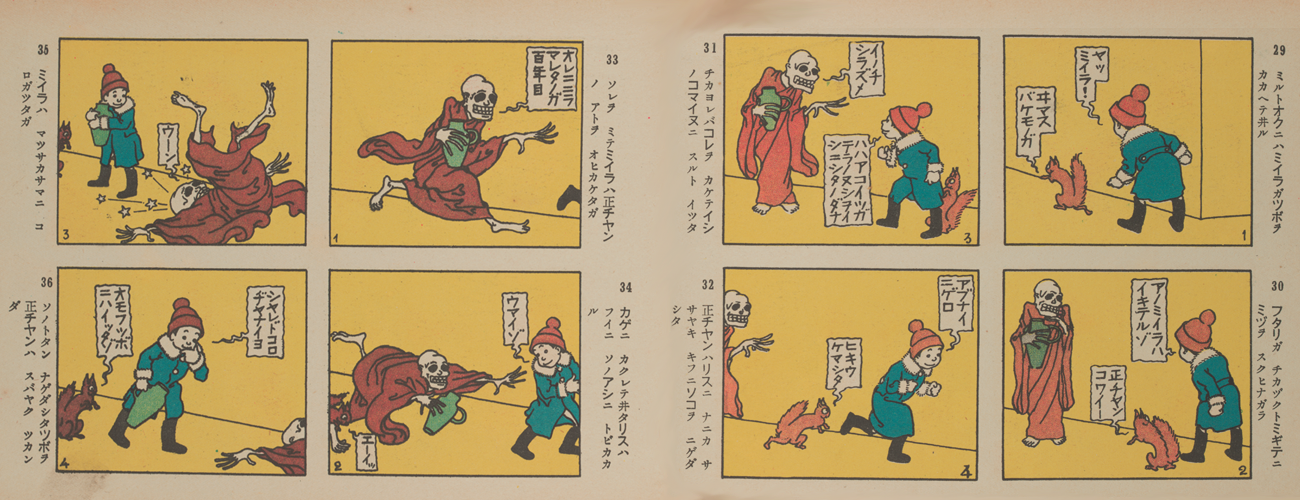

Masthead image from the New York Public Library, public domain Shôchan no bôken by Katsuichi Kabashima, and Shôsei Oda