Side Quest Added: Response 2

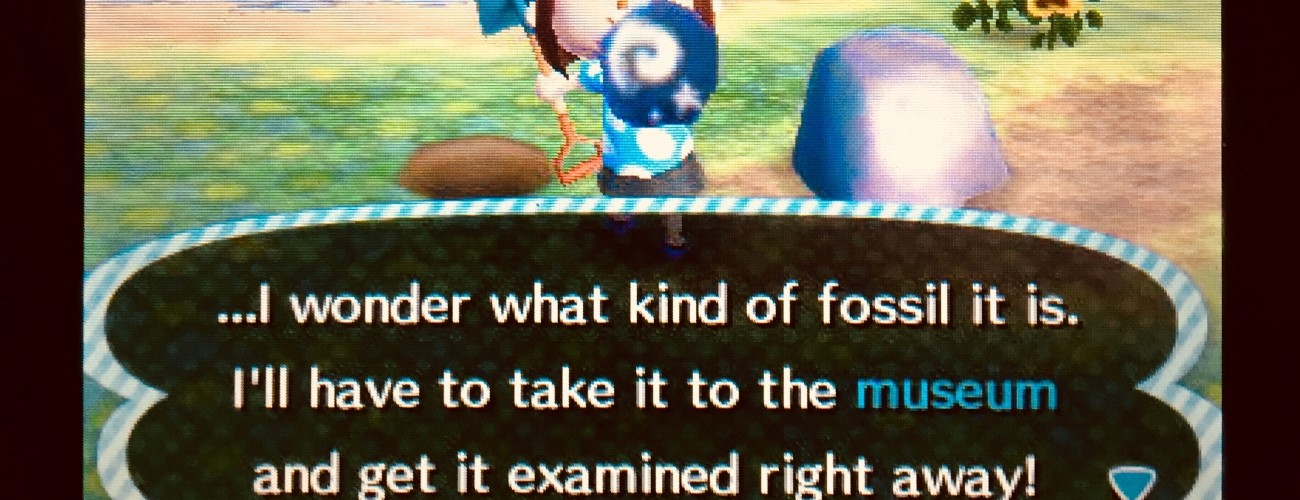

Fitzpatrick’s “Side Quest Added: How Video Game Mechanics Inspire Pseudo-Archaeology” is a quest on its own. Concise and illustrative, I love that the work explores how wholesome-styled games can perpetuate the same pseudoarchaeology as action games.

Generally, I don’t play Stardew Valley and Animal Crossing-style games. Instead, the titles Fitzpatrick mentions in passing, Tomb Raider and Uncharted, reel me in. Those latter titles also have more obvious or more egregious archaeology errors covered. But that’s a response to another piece.

In contrast, the mechanics in games like Stardew Valley and Animal Crossing act as foils to Fitzpatrick’s discussions of Dragon Age and Skyrim, as games that people ignore when it comes to perpetuating stereotypes in archaeology. They’re the kind of game where it feels almost like “oopsies, we supported a colonial perspective on material culture that monetizes cultural heritage” UwU.

What I think is fantastic and hilarious about Fitzpatrick’s highlighting of this is that it’s actually worse than what happens in Tomb Raider and Uncharted. Both action game franchises tend to state their toxic goals in their titles. Filled with gore, violence, theft, and murder those gritty heroes hope to seek or steal treasures and know they’re not being ethical. Instead, Stardew Valley and Animal Crossing’s wholesome aesthetics seem to signal nice and ethical, even when they are far from it.

Beyond that, the side quest mechanic, such as in Dragon Age and Skyrim, deemphasizes the impact of unethical behavior. The feeling of “well I didn’t have to” provides the player distance from the serious implications of the actions included in that quest. An extension beyond this, important for archaeologists, is how we may want to seriously consider how much of archaeological inquiry is a sidequest.

Defined by Fitzpatrick as “providing additional hours of non-essential gaming in exchange for added benefits or bonuses to the player,” much of our field falls into that category. Particularly when we consider how archaeology as a field started and the ways that archaeologists have failed in our mission to be stewards of the past. With much of the excavated archaeological record locked away from the public we purport to serve, it really makes our entire field feel optional rather than necessary.

These actions by archaeologists as players continually relegate our work to side quest rather than main quest. And our practice as gatekeeping rather than stewarding. Even more so when doing archaeology could benefit many more players people if we made those accessible. Therefore, when we do see archaeological tasks as sidequests, the more common role our field tends to play in the lives of the public, we should take the time as Fitzpatrick does to critique its use.

The sidequests that Fitzpatrick focuses on also provide nice intersections with some of the cultural capital discussions brought up by Verstrate 2024. All the games in Fitzpatrick’s work have their own memes and I can see fertile ground for overlap between the kinds of discussions of real archaeology on Tumblr with these sidequests. For example, Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim had an excellent meme about holding dragon bones.

While some might consider dragon bones paleontological, the dragons are sentient beings who have their own material culture. Likely, they consider the remains of their ancestors and relations sacred. If this is the case can we see that meme as a way for us to explore who gets to carry around and use the bones of ancestors in crafting?

This problem also ties this work to the ethical issues highlighted in Van Alst and Cory (2024) around the archaeology of non-human people. Van Alst and Cory’s (2024) discussion of Breath of the Wild (BOTW) parallels Fitzpatrick’s focus on Skyrim and Dragon Age: Inquisition (DAI). While it is unlikely that DAI and Skyrim players expect to engage in ethical and accurate archaeology in their games, these games play a role in understanding archaeology and cultural heritage.

They are also, alongside those in BOTW, examples of how we can understand archaeology as it exists in places with different historical trajectories than our own. They make us consider the same concepts that we wrestle with in archaeology regarding descendant communities and stewards of the past but in places with drastically different communities. While their material culture bears resemblance to ours, those worlds come with their own unique baggage and history within the games.

With the sidequest taking center stage in Fizpatrick’s work, it reminds readers to consider the things that we accept as part of the “norm” of games and of archaeology. What are the underlying messages in games that, when heard enough, start to influence how groups think about what our field does and who our field serves? The repetition of these tropes, similar to Przystupa’s (2024) discussion of the portrayal of Black archaeologists, calls readers and gamers to consider not just the representation within a piece of popular culture but whether that representation causes harm or provides a point of reconciliation.

Cover Image: "Wanderings in North Africa" British Library

Masthead Image: Screenshot from Animal Crossing