Archaeological Markers of History and Indigeneity in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild: First Response

Introduction

Like the Old Man who greets the players at the start of the game, Van Alst and Cory assist readers in navigating the environmental storytelling in The Legende of Zelda: Breath of the Wild(BoTW) in their recent contribution to Epoiesen. The authors show that when a franchise known for creating worlds with a deep history releases an open-world game, an archaeological lens can provide a nuanced reading of the immersive space. Their engagement of landscape artfully considers the impact of the environmental assets on the players and extensively explores the stories and cultures conveyed through the game’s setting. Their critical approach levels up this piece by examining how the game incorporates tropes and biases pertaining to the past that are persistent in both public and academic discourse. In particular, the section on Indigeneity provokes further conversation on representation and real-world contexts.

Like the Old Man who greets the players at the start of the game, Van Alst and Cory assist readers in navigating the environmental storytelling in The Legende of Zelda: Breath of the Wild(BoTW) in their recent contribution to Epoiesen. The authors show that when a franchise known for creating worlds with a deep history releases an open-world game, an archaeological lens can provide a nuanced reading of the immersive space. Their engagement of landscape artfully considers the impact of the environmental assets on the players and extensively explores the stories and cultures conveyed through the game’s setting. Their critical approach levels up this piece by examining how the game incorporates tropes and biases pertaining to the past that are persistent in both public and academic discourse. In particular, the section on Indigeneity provokes further conversation on representation and real-world contexts.

A Framework for Hyrule’s Colonial Legacies

As someone who has critically analyzed the impact of Japanese archaeology on the production of The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2019), I found several points the authors raised resonated with my work. The most salient comments are located in the first and final paragraphs of the section on “Marking Indigeneity.” The authors begin by defining “Indigneous,” which discusses the impact of empire and conquest. Strikingly absent from the game’s storytelling is the concept of Hylian colonization. Instead, Creating a Champion, Nintendo's official publication on the production and design of the game, situates the origin of the Kingdom of Hyrule in a time of myths(2018). In other words, players are intended to understand Hylian political domination over the other races of the region as a convention. This nebulous and mythical claim to the governance of the land parallels historical claims of the ethnic Japanese population to the archipelago as well as other parts of the Pacific. Specifically, the early modern Japanese state embraced the oldest historical records that proclaimed the imperial line to have descended from the gods who bestowed upon their lineage the right to rule the islands of Japan (Siddle 2014). These claims have been used to validate the state’s claim to sovereignty and award it the right to subjugate others, similar to Hylian lore.

The same section on Indigenity concludes by linking players’ positive interactions with in-game communities with the ongoing disregard for Japan’s colonial legacies. This astute observation provides a foundation for additional contextualization. The historical records discussed above and the appropriated terra nullius doctrine (Mason 2012) were used to justify the colonization of the island of Hokkaido, part of the traditional homeland of the Ainu. The government only formally recognized the Ainu as Indigenous in 2019, and there has been no acknowledgment of the nation’s colonial history(Grunow et al. 2019). Instead, both in the game and reality, there is a focus on mutual understanding and collaboration to address other issues. Indigenous races of the Kingdom of Hyrule working in harmony with the Hylians is reminiscent of the government's efforts to promote “peaceful coexistence” between the Ainu and ethnic Japanese in lieu of reparations and restoration (Tsagelnik 2020). Breath of the Wild is not the only game developed in Japan to avoid imperial histories while creating supportive Indigenous populations. For example, recent Pokemon games set in analogs of Hawai'i and Hokkaido introduce Indigenous communities that facilitate the journey of the main character, a settler in Indigenous lands.

The Mystery of Japanese Archaeology

In the latter half of the article, Van Alst and Cory discuss how the Zonai, a mysterious ancient society in the game, draws influences from popular pseudoarchaeological tropes. Lost civilizations and the occult ideology surrounding them have been imported from the West to Japan since the 19th century (Morrow 2023) but have not been applied to the local archaeological record with the same fervor. However, this doesn’t mean Japanese archaeology is entirely immune to romanticized and problematic interpretations of its past, as previously discussed. While not necessarily framed as a “lost civilization,” the Kingdom of Yamatai, mentioned in historical records from the Eastern Han dynasty, is the closest approximation to one in Japan. Various details regarding Yamatai, including its location, have fueled protracted feuds between Japanese archaeologists (Kidder 2007). Interpretations of Yamatai are often wrapped up in conversations concerning national identity, as some scholars use research to extend the imperial line and ethnic identity to pseudohistorical times. The questions surrounding Yamatai also captivated the public and have led to a sizeable collection of literature on the topic (Mizoguchi 2012). Along with the Western concept of lost civilizations, Yamatai demonstrates an enduring fascination with mysteries of the past in Japan. While there is not enough information in BoTW to explore the possible connections between the Zonai and Yamatai, the civilizations' expanded role in the game’s sequel promises the opportunity for greater scrutiny.

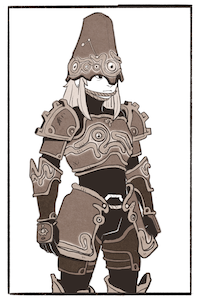

The sense of mystery surrounding the past in BoTW can be seen as a reflection of the general public's unfamiliarity with Japanese archaeology, which coincided with the rise of a highly professionalized archaeological management system in postwar Japan(Okamura 2014). A surge in public interest coinciding with the game's release has challenged the traditionally top-down approach to archaeological management, creating tension between professional interpretations and the public's growing curiosity. Within the last decade, Japan has seen a boom in public interest in archaeology centered on the Jomon period (ca 16,000 ~ 2,500 cal BP), a prehistoric period marked by the spread of diverse hunter-gatherers throughout the archipelago, leading to a multivocal wave of interpretations. A recent back-and-forth in printed form captures the burgeoning dissonance between academics and the public (Mochizuki 2023, Takekura 2021). In other words, until recently, the production of knowledge of the past has been strictly under the control of specialists since the postwar period. This system is also evoked in the various withdrawn, singularly-focused scholars, academics, and archaeologist non-player characters encountered in the game (Figure 2). These characters aren’t often forthcoming with their information, and several sidequests involve acquiring it through deceptive means.

Figure 2. Archaeologists and historians Link can encounter in the game (Nintendo 2017).

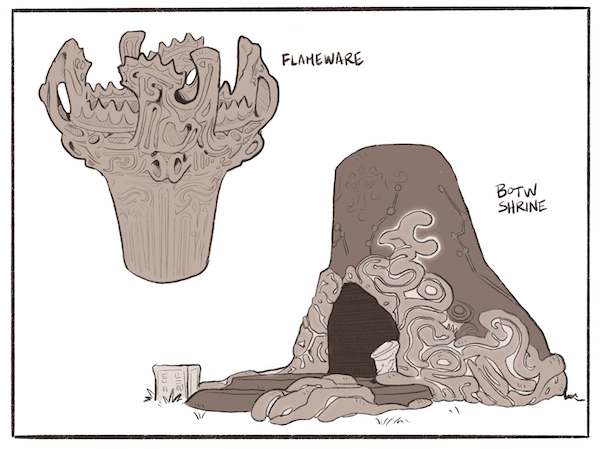

While the “Lost Civilization” of the Zonai may share a greater affinity with Western conventions, the designers drew influence from Japanese archaeology for the Shiekah’s ancient technology. This choice, while creating a sense of the past, reflects a field that often prioritizes dominant narratives over diverse perspectives. Jomon pottery, specifically flameware and clay figurines known as dogū, were referenced in the form and decoration of in-game assets like the Guardians (Nintendo 2014)(Figure 3). The organic swirling designs on Jomon pottery were then integrated into the game as stylistic markers for ancient Sheikah creations found more readily across the continent than the Zonai ruins. The contemporary home of the Sheikah, which is stylistically coded to evoke a traditional Japanese environment, and their history impart an unquestioning sense of ownership of the past, echoing claims in Japan. With the recent inscription of the Northern Jomon Sites to the World Heritage list, the discourse surrounding the sites has been one of framing the Jomon as “the fundamental culture revealing core Japanese values”(Abe 2019) as well as emphasizing a genetic legacy(Drianda 2021). Yet, with sites extending into Hokkaido, the lack of engagement of the Ainu as a stakeholder community brings the conversation back to the section on Indigeneity. The limited narrative around ancient civilizations in Breath of the Wild mirrors the marginalization of the Ainu within the archaeological discourse in Japan. This reinforces various calls throughout these articles for popular media to engage with diverse perspectives and challenge singular narratives of the past.

Figure 3. Jomon flameware pot and a shrine from Breath of the Wild.

Decolonizing or Recolonizing Hyrule

I’d like to conclude by touching upon the parable of the appropriation of archaeology central to the game’s story. Ganon, the main antagonist, mobilizes ancient Sheikah tech to dominate Hyrule. To some extent, parallels could be drawn to the weaponizing of cultural artifacts and history by colonial forces to establish a narrative of superiority that has perpetuated the oppression of Indigenous communities. Part of the gameplay involves fighting artifacts awakened by the antagonist to free Hyrule from his influence, a struggle that parallels the decolonization of archaeology. However, while Western archaeology has been grappling with its colonial legacies for several decades, Japan has not developed a framework for Indigenous archaeology (Kato 2017). Instead, postwar Japanese archaeology adopted principles of empiricism, objectivity, and positivism that persist to the present, aiming to disengage from prior interpretive methodologies imbued with imperialistic frameworks(Hisoya 1996). This paradigm shift is echoed in the strategy of the main character, Link, who utilizes the same ancient technology to destroy the system of subjugation established by Ganon. The vague end scenes leave the players wondering what will be established in its place- will the colonial Kingdom of Hyrule be rebuilt, and what role will the ancient artifacts and sites play in the future of the land? While the state of Japanese archaeology may provide some clues, other answers can be found in the sequel, Tears of Kingdom, as predicted by the authors. However, the newest installation also creates a tangible and intangible palimpsest of the past, requiring several more articles to unravel. I look forward to seeing how Van Alst and Cory approach the lands above and below Hyrule.

I’d like to conclude by touching upon the parable of the appropriation of archaeology central to the game’s story. Ganon, the main antagonist, mobilizes ancient Sheikah tech to dominate Hyrule. To some extent, parallels could be drawn to the weaponizing of cultural artifacts and history by colonial forces to establish a narrative of superiority that has perpetuated the oppression of Indigenous communities. Part of the gameplay involves fighting artifacts awakened by the antagonist to free Hyrule from his influence, a struggle that parallels the decolonization of archaeology. However, while Western archaeology has been grappling with its colonial legacies for several decades, Japan has not developed a framework for Indigenous archaeology (Kato 2017). Instead, postwar Japanese archaeology adopted principles of empiricism, objectivity, and positivism that persist to the present, aiming to disengage from prior interpretive methodologies imbued with imperialistic frameworks(Hisoya 1996). This paradigm shift is echoed in the strategy of the main character, Link, who utilizes the same ancient technology to destroy the system of subjugation established by Ganon. The vague end scenes leave the players wondering what will be established in its place- will the colonial Kingdom of Hyrule be rebuilt, and what role will the ancient artifacts and sites play in the future of the land? While the state of Japanese archaeology may provide some clues, other answers can be found in the sequel, Tears of Kingdom, as predicted by the authors. However, the newest installation also creates a tangible and intangible palimpsest of the past, requiring several more articles to unravel. I look forward to seeing how Van Alst and Cory approach the lands above and below Hyrule.

References Cited

Abe, Chiharu (2016). ‘ Strategies of Cultural Heritage Management in Hokkaido, Northern Japan from the Perspective of Public Archaeology,’ in A.P. Underhill and L.C. Salazar (eds.) Finding solutions for protecting and sharing archaeological heritage resources. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. (2017) Nintendo Switch[Game]. Kyoto: Nintendo.

Drianda, Riela Provi et al. (2021). ‘Time-slip journey to Jomon period: A case study of heritage tourism in Aomori Prefecture, Japan,’ Heritage, 4(4), pp. 3238–3256. doi:10.3390/heritage4040181.

Gomes, A. (2019). ‘ Jomon Booms and Bombs: Situating The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild within the “Jomon Boom” Trend.’ Theoretical Archaeology Conference 2019 / Institute of Archaeology, London: UK, 16 December.

Grunow, Tristan R. et al. (2019). ‘Hokkaidō 150: Settler colonialism and Indigeneity in modern Japan and beyond’, Critical Asian Studies, 51(4), pp. 597–636. doi:10.1080/14672715.2019.1665291.

Hisoya, L.A. (1996). ‘Archaeology of No Theory -How to understand Japanese archaeology? Theoretical Archaeology Group Conference 1996, Liverpool: UK, December.

Kato, Hirofumi. (2017). ‘The Ainu and Japanese Archaeology: A Change of Perspective.’ Japanese Journal of Archaeology 4: 185-190.

Kidder, J. Edward. (2007). Himiko and Japan’s elusive chiefdom of Yamatai: archaeology, history, and mythology. Honolulu, University of Hawai'i Press.

Mason, Michele M. (2012). Dominant Narratives of Colonial Hokkaido and Imperial Japan: Envisioning the Periphery and the Modern Nation-State. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mizoguchi, Koji. (2012). ‘Archaeology in the Contemporary World (2006)’. In S. Sullivan and R. Mackay (eds.) Archaeological Sites: Conservation and Management. Los Angeles: Getty Publications.

Mochizuki, Akihide, Takuya Kokobu. et al. (2023). Dogū o yomu O yomu. Tōkyō: Bungaku tsūshin.

Morrow, Andrew (2023). ‘Conceptualising Secret Societies and Conspiracy Theories in Imperial Japan: From Countering Socialism to Rescuing Jewish Refugees’, in E. Asprem, M. Pasi, and F. Piraino (eds.) Religious dimensions of conspiracy theories comparing and connecting old and new trends. London, UK: Routledge, Taylor & Francis.

Nintendo (2018). The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild--Creating a Champion. Milwaukie, OR: Dark Horse Books.

Okamura, Katsuyuki (2012). ‘From Object-Centered to People-Focused: Exploring a Gap Between Archaeologists and the Public in Contemporary Japan,’ in Okamura, K. and Matsuda, A. (eds.) An New Perspectives in Global Public Archaeology. New York: Springer, pp. 77–86.

Siddle, Robert (2014). Race, resistance and the Ainu of Japan. Abingdon U.K.: Routledge.

Takekura, Fumito (2021). Dogu o Yomu: Hyakusanjunenkan Tokarenakatta Jomon shinwa no nazo. Shobunsha.

Tsagelnik, Tatsiana (2020). ‘Discourse of Silencing in the Context of the 150th Anniversary of the Naming of Hokkaido : Representation of Ainu-Wajin Relations in the Television Drama “Eternal Nispa, the Man Who Named Hokkaido, Matsuura Takeshiro.”’ Identity and Cultural Icons in a Multicultural World : Ethnicity, language, nation, pp. 125–143. doi:http://hdl.handle.net/2115/77222.

Cover Image "Image from page 339 of 'Unbeaten Tracks in Japan ... New edition, abridged'"" British Library

Masthead Image reproduces Figure 1 by the Van Alst and Cory.