The Melian Dilemma: Remaking Thucydides: Second Response

Game theory and the Melian Dialogue

It is clear that Thucydides had “games” in mind whilst writing, editing and rewriting his History – his devotion to the theme of the agon – literally the “contest” or “struggle” attests to it. Thucydides’ gamification is so patent that my doctoral thesis attempts to show that he may have described events with more rigour than we had previously imagined possible.1 Historical characters are imbued with an introspective dialogue that appears as if each one were constructing a game of cunning strategies that considers possible actions and each outcomes’ payoffs. Recorded actions and private thoughts are intertwined throughout. Neville Morley’s gamification of one of Thucydides’ most famous episodes is a natural outcome from reading Thucydides’ text. Others have recently made this connection as well. Morley blogs about how a notorious game theorist and former finance minister of Greece, Yanis Varoufakis, wrote a paper inspired by the episode.2 Nonetheless, Thucydidean scholars on the whole admit that “he never offers precepts or explicit lessons”, as Morley writes, rightly pointing to Hobbes who best stated the problem.

Like many of Thucydides’ gem set-piece narratives, the episode within which the dialogue sits (5.84-116) has been interpreted in an almost endless number of ways. The interpretation I offer below is a variant form to Morley’s interpretation, in that it falls within Morley’s umbrella framework of gamification but seeks to be a more ‘rigourous’ method – to use the lingo from the discipline of economics – which merely means that it restricts our view of how thoughts explain a player’s actions. It is not better or worse than other methods, just different. The temporal structure of the narrative and a player’s power to affect another’s action is of paramount importance for a game theoretic analysis. A couple of questions need to be clearly answered for the Melian Dialogue to be described accurately. Which player was the first or second mover? Whose actions determined the outcome? Once these questions are answered the game is fully described. Only then can we can find what game theorists call a ‘solution’ – in other words, the most likely course of action taken by each player given their possible payoffs. This solution should in theory mimic the historical outcome and thus provide an explanation to why players acted the way they did. This is what we explore below.

Game theoretic analysis of the dialogue (5.84.1-114)

The Melian Dialogue is unique in its narrative structure, being the only dialogue in the History.3 The narrative is introduced as a sort of negotiation, such that the Athenians send ambassadors to put forward a proposal to the people of Melos. Melos remember is a Spartan colony that refused to submit to the control of the Athenian empire and desired to remain neutral. The Athenians make a single offer, whilst the Melians attempt to negotiate for better terms, attempting to submit the offer to arbitration in order to revise it. Arbitration or any form of justice, the Athenians argue, is only possible among two players of equal strength and therefore their take it or leave it ultimatum is best suited for this situation.4 The Melians attempt to grasp at moral and ethical reasons for why the Athenians should reply to a counter offer. The Athenians stand by their ultimatum and enforce it, simply because these generals are mandated negotiating agents.

Temporal structure

The basic temporal structure of the negotiation is clear in that there is a proposal on the part of the Athenian ambassadors, followed by a reply on the part of the Melian magistrates and ruling men. The Athenians make a proposal (λόγους πρῶτον ποιησομένους ἔπεμψαν πρέσβεις, 5.84.3). The narrative is only a conversation or dialogue because the Melians insist on holding the meeting in private before the magistrates and leading men. The ambassadors therefore request permission to deliver their offer informally (καθ᾽ἡσυχίαν = lit. ‘at leisure’, to take their time or informally, 5.86),5 since there would be no formal proposal to the people. The usual form of address, as the ambassadors point out, would have been in the form of a single continuous speech before the popular assembly (μὴ ξυνεχεῖ ῥήσει... ἑνὶ λόγῳ, 5.85). Thus, the Athenians ask for permission to make their proposal informally: “And firstly say if what we are saying is to your liking” (καὶ πρῶτον εἰ ἀρέσκει ὡς λέγομεν εἴπατε., 5.85). The Melians grant it: “Let the negotiation be in the way you propose, if it seem good to you” (καὶ ὁ λόγος ᾧ προκαλεῖσθε τρόπῳ, εἰ δοκεῖ, γιγνέσθω, 5.87). A dialogue or conversation ensues.

Content of proposal

Both agree that their negotiation is about the survival of the Melian state (περὶ σωτηρίας, 5.87 and 5.88). The Athenians will grant them survival if they submit as subjects to the Athenian empire. Given the Melians are inferior in strength to themselves, the Melians should accept whatever the stronger is so kind to allow them to keep, in this case their lives (5.89). The Athenians insist that it is common knowledge (ἐπισταμένους πρὸς εἰδότας, lit. you know as we both know, 5.89) that expediency is justice. The Melians object to the Athenians’ definition of expediency (to xumpheron, 5.90) and insist that the Athenians offer fair terms (to diakaion, 5.90) rather than merely survival, which amounts to slavery (douleian, 86). The Athenians retort that justice is only an option among parties that are to some degree equal.6

τὰ δυνατὰ δ᾽ ἐξ ὧν ἑκάτεροι ἀληθῶς φρονοῦμεν διαπράσσεσθαι, ἐπισταμένους πρὸς εἰδότας ὅτι δίκαια μὲν ἐν τῷ ἀνθρωπείῳ λόγῳ ἀπὸ τῆς ἴσης ἀνάγκης κρίνεται, δυνατὰ δὲ οἱ προύχοντες πράσσουσι καὶ οἱ ἀσθενεῖς ξυγχωροῦσιν.

We are concerned with the possible [actions] we both truly believe are done. You know, as well as we do, that within the limit of human calculation judgments about justice are made between those with an equal power to enforce it (lit. with equal necessity), otherwise possible actions are defined by what the strong do and the weak accept (lit. have to comply). (5.89)

This passage is often hailed as the source behind the realist jingle: might is right.7 It is stern and calculating without a hint of emotional involvement. This is a recurring theme in Thucydides and other writers.8 The dialogue revolves around the advantage (χρήσιμον) either side can persuade the other they can offer the other. After several tos and fros, the Athenians insist that the Melians’ considerations of future benefits and costs are of no consequence, and that it is the present deliberation over safety, from which they have strayed, which is being considered (5.111.2, 5). The Athenians at the end of the conversation formally make an offer that the Melians become allies, which would allow them to keep their own land but must pay tribute.9 These conditions are distilled into “a choice between safety or war” (δοθείσης αἱρέσεως πολέμου πέρι καὶ ἀσφαλείας, 5.111.4)

The Athenians now withdraw from the negotiations (μετεχώρησαν ἐκ τῶν λόγων, 5.112.1). The Melians deliberate amongst themselves and reach the same conclusion they had before, which was not to yield (οὐκ ἤθελον ὑπακούειν, 5.84.2), and reply to the Athenians (ἀπεκρίναντο τάδε, 5.112.1-2). They will not accept (5.112.1-2), unless the terms are beneficial to both (5.112.3). After the Melian reply (ἀπεκρίναντο), the Athenians dissolve the negotiations (διαλυόμενοι ἤδη ἐκ τῶν λόγων) informing them of the consequences of their rejection: they will lose everything (5.113).

This dynamic environment, although not immediately apparent as a result of the conversational format, is in fact an ultimatum. The Athenian offer is made only once and they withdraw to allow the Melians to make one decision (ἐς μίαν βουλήν, 5.111). It important to note that the form of the dialogue is an ultimatum but only if focalized through Athenian rhetoric.

Descriptive Theory

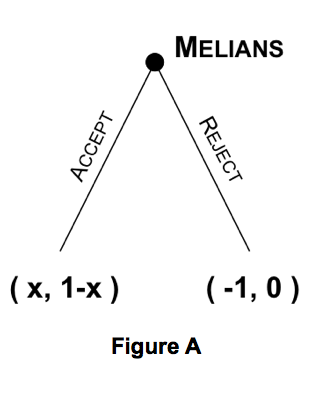

The Melian rhetoric strains to accomplish arbitration but fails due to Athenian intransience. The Athenians are concerned fundamentally with arguing why their offer is acceptable for the Melians; with persuading the Melians (peistheisi, 5.86). First, the Athenians emphasize that there is no deterrent mechanism to halt their actions. As a stronger state than Melos, Athens has no fear that they will be weaker and therefore natural law necessitates (ὑπὸ φύσεως ἀναγκαίας) that the stronger rule the weaker (5.105.2, cf. 1.83).10 Second, there is no possibility for renegotiation. The demos at Athens had voted, commissioned and deployed the military expedition to Melos with their instructions (στρατοπεδευσάμενοι, 5.84.3). The generals were executing orders and therefore were lacking in authority to make any compromise.11 The fact being that capitulation was not an option and that the form of capitulation would be by submission or annihilation. Submission they argued benefits both (5.91). The Athenians are constrained to set an offer that calculates the present alone to which the Melians initially agree to discuss (5.87) (Figure A).

The Athenians couch the arguments in terms of soteria 12 or preservation of the Melians’ lives and territory in return for the payment of tribute (5.88, 99, 111.4-5). This, the Melians believe amounts to slavery (5.86, 92, 100) even though they concede that this would still ensure their safety (5.88).13 We can assume that Melos’ current status as independent, free and neutral (5.112.2) may be represented by the number 1, as in 100%, so that soteria is just a portion of that and may be represented by a proportion x. For example, x could be 20% or 60% depending on whether you value freedom a little or a lot, respectively. The Athenian payoff from Melos’ subjection is represented as (1-x) to describe the transference of assets and regulatory power from Melos to Athens. If the Melians reject, the destruction of Melos would mean the loss of life and country and is represented by -1, which describes the irreversible loss of “everything” (5.113, and 5.103,111.3). The Athenians believe that if Melos is destroyed they would retain their current hegemony without expanding the empire (5.97). This we can represent as 0, since nothing is accrued to the Athenian empire and the status quo is maintained for Athens. The costs of war are seemingly absent in the discussion, so likewise are not represented here.

Solution Theory

The Melians do not honour their initial agreement to consider the present circumstances (5.111). They understand the Athenian stance that the current state is already one of war and that the refusal to accept the offer of submission means the investment of the city (5.86). They nonetheless disagree with this Athenian stance regarding the state of the world, arguing that the Athenians should consider their future gains from Melian neutrality (5.98, 112.3). With the aid of hypothetical calculations about future consequences, the Melians themselves try to persuade the Athenians that there will be a great cost to Athenian hegemony if the Athenians besiege Melos (5.87-111). The dialogue is traditionally read in moral terms, reasonably, but this does not tell the full story. The Athenians close the dialogue pointing out the folly of their belief in Sparta, as well as their reliance on fortune (tuche) and hope (elpis). The Athenians continue the poetic ‘present-future’ or ‘near-far’ theme that the Melians judge (κρίνετε) the uncertain future to be clearer than the present (5.113, see 5.86,87).14 Certainty of the present can be seen (τῶν ὁρωμένων) and miscalculations occur when this certainty is projected into the future.

Ober and Perry have argued that in Thucydides the correlation of hope and the over-estimation benefits have low-probability of success.15 In game theoretic terms, this type of miscalculation is caused by weighing future prospects with greater certainty than they actually possess. This is called risk-loving or risk-seeking behaviour. Although the Melians have apparently fallen into this trap, the Athenians themselves seem to be prone to risk–loving behaviour too. This has not only been noted by the Corinthians’ comparison between the risk-loving Athenians and risk-averse Spartans (1.70), 16 but also in the dialogue itself the Athenians assume throughout that Melos will lose if they choose to resist (5.103, 113).

In factual historical terms, the Athenians capture Melos with far greater difficulty than they led the Melians to believe in the dialogue. The Melians suffer from what the behavioural economists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky call the certainty effect and the Athenians suffer from overconfidence. 17 The former chooses “a small hope of avoiding a large loss” over a manageable failure, the latter of “exaggerated optimism“, from which both over-weigh their probabilities of success. When states have conflicting estimates of the likelihood of victory and both sides are optimistic about their chances, a range for a bargaining agreement is obscured and limited. If both players are risk-loving, then the offer will be lower, and acceptance will require a higher offer in order for both to prefer agreement over the gamble of war. Conversely, when the expected payoff of success is calculated by risk-neutral or risk-averse players, there is always a bargaining range for agreement. A share of whatever is at issue is preferred to the downside of losing a war, regardless of whether it is a fifty-fifty chance or an even higher chance of winning. 18 The case in the Melian Dialogue is the reverse where the gamble, no matter how grim the odds, is preferred to any offer.

Melians Reject the Offer and Final Engagement

When the Melians reject the Athenians’ offer, the Athenian ambassadors return to the encampment in the outskirts of the city. 19 The generals receive the news that the Melians yielded nothing (ὡς οὐδὲν ὑπήκουον οἱ Μήλιοι) and immediately invest the city (5.114.1). 20 The Athenian generals begin by building a wall around it (εὐθὺς ... περιετείχισαν κύκλῳ τοὺς Μηλίους, 5.114.2). The Athenians allocate the wall-building work among the several cities (διελόμενοι κατὰ πόλεις) which had joined the campaign against Melos. Once built, the Athenians retreat “with most of their army” (τῷ πλέονι τοῦ στρατοῦ), leaving only a guard to besiege the place (ἐπολιόρκουν τὸ χωρίον, 5.114.2). Having successfully breached the siege twice against this partial force of the Athenians, the Athenians return with “the rest of the army” (στρατιᾶς ... ἄλλης). The Melians were defeated by the strength of the siege and also with the help of traitors from within the city (5.116.3). It was not an easy victory at all! Nonetheless, the Athenians did succeed and killed all the men of military age, enslaved the women and children, and sent out 500 colonists to resettle the city (5.116.4). The result was the complete obliteration of the Melian state.

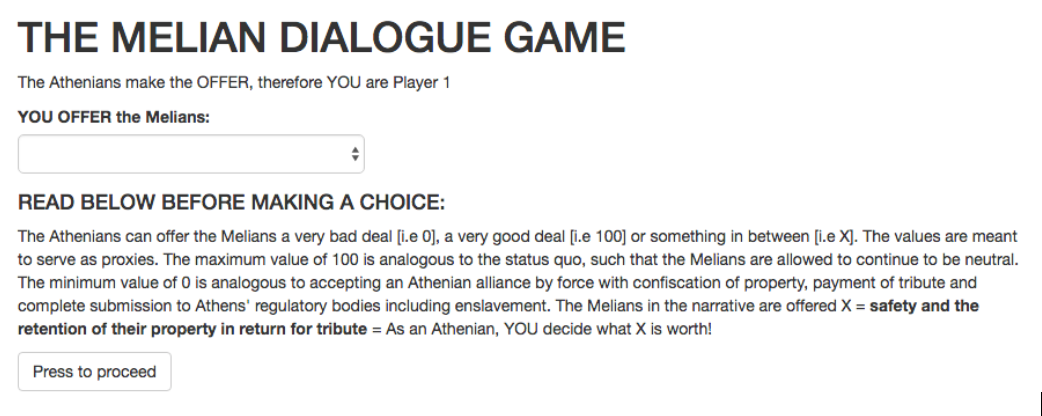

The Melian Dialogue Game

As a result of this particular interpretation of the narrative, the Melian Dialogue Game App which includes the Athenian and Melian biases has been coded in R using gtree, which was developed by Prof. Dr. Sebastian Kranz, and uploaded to shinyapps.io. The app may be played at https://melos.arch.cam.ac.uk/UltimatumGame/.

Endnotes

1 Dal Borgo (2016). ↩

2 Morley (https://thesphinxblog.com/2015/03/27/the-melian-dilemma-varoufakis-thucydides-and-game-theory/); Varoufakis (1997), (2014). ↩

3 Hudson-Williams (1950) 156-69; Macleod (1983) 52-54, on the rhetorical form of the dialogue as a "common deliberation", unlike a Platonic dialogue taking the form of consistent questions and refutations; CT. 3.216-225 for bibliography. ↩

4 Chwe (2013) 222-224, on bargaining and status as a commitment device. "If I am stronger than you, I do not need to consider your situation because nothing you do can help or harm me." ↩

5 Macleod (1983) 54, for κρίνετε as a word used in the assembly Cf. 1.87.2, 120.2; 2.40.2; 3.37.4, 43.5; 6.39.1). ↩

6 Bosworth (1993) 39, esp. 39ft.45 and 46.”This does not of course imply that justice subsists between powers of approximately equal magnitude, as is commonly alleged. ... but that justice subsists between individuals who are to some degree equal and not between those who are blatantly unequal, as slaves and their owners.” See Arist.NE.v.1131.a ff, Pol.3.1280a11, δοκεῖ ἴσον τὸ δίκαιον εἶναι, 1282.b.18. ↩

7 Mary Beard (2010) praising the accuracy of the translations in CT 3, "the most favorite of all Thucydidean catchphrases, repeated in international relations courses world over, and a founding text of the "realist" political analysis: 'The strong do what they can, the weak suffer what they must.'' … [Simon Hornblower’s] more accurate translation is: 'The powerful exact what they can, and the weak have to comply.'" This version detracts from the jingle "might is right"; Welch (2003) agrees.. ↩

8 E.g. 1.73.2, "it has always been established practice for the weaker to be ruled by the stronger", with HCT i.236-44; cf. Antiphon DK87 fr.44a ll.6-33. ↩

9 CT 3.248-9. ↩

10 In Melian Dialogue 5.105, 103, 111.4 in addition to references to the Melians as islanders 3.91; 5.84, esp. Athens master of the seas 5.97; In bk 5: 31; 33; 35.1; 39.1; 47.1; 54-6; 79.1; CT 3.216ff. This does not exclude a further layer that the Athenians do speak of danger 5.99 and also of other’s perceptions that they are afraid 5.97. A richer model would be needed to include these factors. ↩

11 Bosworth (1993) 31-2; esp. Hobbes (1629) To the Readers: Thucydides "introduceth the Athenian generals, in a dialogue with the inhabitants of the Isle of Melos, pretending openly for the cause of their invasion of that isle, the power and will of the state of Athens; and rejecting utterly to enter into any disputation with them concerning the equity of their cause, which, he saith, was contrary to the dignity of the state. To this may be answered, that the proceeding of these generals was not unlike to divers other actions, that the people of Athens openly took upon them: and therefore it is very likely they were allowed so to proceed. Howsoever, if the Athenian people gave in charge to these their captains, to take in the island by all means whatsoever, without power to report back unto them first the equity of the islanders’ cause; as is most likely to be true; I see then no reason the generals had to enter into disputation with them, whether they should perform their charge or not, but only whether they should do it by fair or foul means; which is the point treated of in this dialogue." ↩

12 Macleod (1983) 58, σωτηρία/ ἀσφάλεια are "key-words". ↩

13 Macleod (1983) 57; CT 3.220, 5.92, 94 slavery advantages the Athenians n.b. 5.93 ad loc. citing Canfora 58f. that Athenians agree with the assessment of slavery. ↩

14 CT 3.221. ↩

15 Ober, Perry (2014) 209-11. ↩

16 Ober, Perry (2014) 215-18; Ober (2010) 65-87. ↩

17 Kahneman (2011) 310-21, 255-65; Kahneman, Tversky (2000) 36 "The overestimation that is commonly found in the assessment of the probability of rare events." ↩

18 Fearon (1995). ↩

19 5.114.1, καὶ οἱ μὲν Ἀθηναίων πρέσβεις ἀνεχώρησαν ές τὸ στράτευμα; Cf. στρατοπεδευσάμενοι ... ἐς τὴν γῆν, 5.84.3. ↩

20 Note the difference between the single reply of the Melians who do not yield to this one thing = “nothing” (οὐδὲν), as opposed to the Athenians at 1.139.2 who do not yield to multiple things = “to any of these” (οὔτε τἆλλα). ↩

Bibliography

Beard, M. (2010). "Which Thucydides Can You Trust?" The New York Review of Books September 30, 2010.

Bosworth, A. B. (1993). "The Humanitarian Aspect of the Melian Dialogue". JHS, 113, 30-44.

Chwe, M. S. (2013). Jane Austen, Game Theorist. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Dal Borgo, Manuela. 2016. "Thucydides: Father of Game Theory", PhD, University College London. discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1507820/

Fearon, J. D. (1995). "Rationalist Explanations for War". International Organization, 49 (3), 379-414.

Hobbes, Thomas. 1629. "To the Readers", in Eight Books of the Peloponnesian Warre Written by Thucydides the Son of Olorus: Interpreted with Faith and Diligence Immediately out of the Greek by Thomas Hobbes, London: Henry Seile

Hornblower, S. (1991-2008). A Commentary of Thucydides. Oxford: Oxford University Press. (cited as CT 3)

Hudson-Williams, H. L. 1950. "Conventional Forms of Debate and the Melian Dialogue." American Journal of Philology 71: 1956-69.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (2000). Choices, Values and Frames. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kahneman, D., (2011) Thinking, Fast and Slow. London: Penguin Books.

Macleod, C. (1983). Collected Essays. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Morley, N. (2015, March 27) "The Melian Dilemma: Varoufakis, Thucydides and game theory" [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://thesphinxblog.com/2015/03/27/the-melian-dilemma-varoufakis-thucydides-and-game-theory/

Ober, J., & Perry, T. (2014). "Thucydides as a Prospect Theorist". Polis, 31, 206-232.

Varoufakis, Y. (1997). "Moral rhetoric in the face of strategic weakness: experimental clues for an ancient puzzle". Erkenntnis , Vol. 46, 87-110.

Varoufakis, Y. (2014) Economic Indeterminacy: a personal encounter with the economists’ peculiar nemesis, London & New York: Routledge.

https://www.flickr.com/photos/britishlibrary/11083047784/

Cover Image "Image taken from page 111 of 'The Baby's Museum; or, Rhymes, jingles and ditties, newly arranged by Uncle Charlie'" British Library

Masthead Image Courtesy of Neville Morely